Dear Capitolisters,

Unless you were too busy celebrating the one-year anniversary of Capitolism last week, you probably heard that the White House on Thursday announced a new plan to combat COVID-19 on several fronts. Undoubtedly the most controversial of the president’s proposals is a forthcoming federal rule—issued by the Department of Labor on an expedited, “emergency” basis—that major private U.S. employers require their employees to be vaccinated or to submit to weekly testing. Because the new mandate hasn’t actually been issued yet, coming to definitive conclusions about it is a bit tricky (to say the least). Nevertheless, given how significant—and in my view radical and problematic—the White House proposal appears to be, it’s well worth our time today to dig into what we do know about the order and all of the various concerns that it raises.

What the Mandate Does

We don’t have the actual text of the mandate just yet—and as we’ll discuss below, that matters a lot—but here’s what we know so far from the White House:

The Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) is developing a rule that will require all employers with 100 or more employees to ensure their workforce is fully vaccinated or require any workers who remain unvaccinated to produce a negative test result on at least a weekly basis before coming to work. OSHA will issue an Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) to implement this requirement. This requirement will impact over 80 million workers in private sector businesses with 100+ employees …

To continue efforts to ensure that no worker loses a dollar of pay because they get vaccinated, OSHA is developing a rule that will require employers with more than 100 employees to provide paid time off for the time it takes for workers to get vaccinated or to recover if they are under the weather post-vaccination. This requirement will be implemented through the ETS.

Goldman Sachs estimates that this broad mandate would affect approximately 25 million currently unvaccinated U.S. workers, eventually pushing about 12 million of those (4.6 percent of the adult population; 9.6 percent of the private sector workforce) to get vaccinated. We further know that violations of the proposed Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) would carry a fine of $14,000 per violation (i.e., an unvaccinated or untested worker).

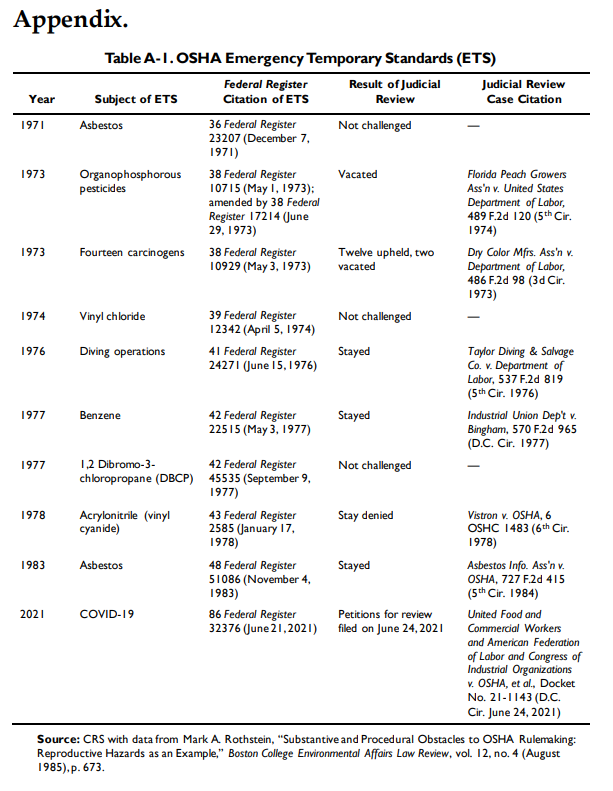

According to a great Congressional Research Service primer, OSHA has invoked its ETS powers only a few times since the 1970s, and only once since 1983—earlier this year when the agency required certain health care providers to implement various COVID-19 safety protocols (PPE, ventilation, etc.), but not mandatory vaccination, to protect health care workers in these settings from the virus.

Thus, there’s a little precedent for the proposed OSHA action, though it still raises serious legal, practical, and other issues that, in my view, argue against implementation.

Legal Concerns

Most of the initial criticism of the proposed mandate stems from its questionable legality under both the Constitution and relevant authorizing statute. My Cato colleague Ilya Shapiro finds three potential constitutional flaws, relying heavily on recent Supreme Court precedent on Obamacare’s insurance mandate:

-

Separation‐of‐powers: “this sweeping new regulation is being imposed by presidential diktat, with related claims about the proper scope of OSHA’s statutory authority and whether Congress can even delegate such broad power to the executive branch.”

-

Interstate Commerce Clause: “[E]ven if the executive branch is permissibly interpreting the relevant federal laws, these kinds of impositions are hardly a regulation of interstate commerce (or the use of any other constitutionally enumerated power): states have general police powers to regulate for public health and safety, but the feds don’t.”

-

Necessary and Proper Clause: “[F]orcing private businesses to do the government’s dirty work isn’t a ‘proper’ means of effectuating the goal of limiting the pandemic. .… [and] the federal government can’t now commandeer businesses to impose mandates on individuals that it can’t impose directly.”

The mandate’s statutory weakness may be even more significant. In particular, Cato’s Walter Olson, GMU’s Ilya Somin, and Case Western Reserve’s Jonathan Adler each find potential problems under the law authorizing OSHA to issue an ETS, and they note that—as shown in the CRS chart above—the courts have heavily scrutinized past ETS invocations (fully upholding only one of the six that were challenged in court). Somin and Adler disagree on some of the technicalities, but everyone seems to agree that the biggest hurdle is the law’s requirement that OSHA may issue an ETS only where doing so is “necessary” to protect employees from a “grave danger” in their workplaces. Even assuming one can consider COVID-19 to be a “grave danger” for most of the working age population, it’s questionable—at best—to claim that a nationwide vaccine mandate applied to all workers at all large firms is “necessary” to protect these same workers from a “grave danger” that almost all of them can mitigate themselves (primarily with a free and widely available vaccine, but also with a good mask, distancing, or in some cases remote work). It’s even more questionable when less onerous—not to mention more lawful and potentially more effective—policy alternatives still exist.

As Adler points out, there are likely ways that the Biden administration could reduce the ETS’ potential vulnerabilities under the statute, for example by limiting it to only firms where there’s a serious risk of infection/spread and by exempting certain workers (e.g., those who have had COVID-19 or work remotely). However, doing so would significantly limit the order’s scope and impact, and it would directly contradict the White House’s own descriptions of the forthcoming ETS (i.e., that it would affect “over 80 million workers in private sector businesses with 100+ employees”). At this point, there’s really no reason to give the White House the benefit of the doubt here—especially because OSHA is intentionally bypassing the normal “notice and comment” rulemaking process that would give us some clarity.

Design Concerns

The proposed ETS also raises several concerns about the order’s design and ultimate efficacy. For starters, it appears to ignore the role of natural immunity, as Cato health scholar Dr. Jeff Singer noted last week:

Several studies, including this recent one from Israel, show people with prior COVID-19 infections acquire immunity that is equal to or better than those with vaccine‐induced immunity. That’s why Israel, the U.K., and most European countries give entry passes to people who prove prior COVID-19 infection in lieu of vaccination. Many researchers believe people with natural immunity don’t need to get vaccinated or, at the most, just need one of the two mRNA vaccine doses. Alas, the presidential order doesn’t take any of this into account.

The ETS also seems to be both over- and underinclusive. On the former, the order does not (yet) distinguish between businesses that, as noted above, are particularly risky environments or those that have a clear connection to public health or public accommodation (e.g., medical facilities, large venues, or customer-facing businesses like restaurants). Thus, for example, a large U.S. telemarketing company that has little to no medical or public interaction (save perhaps the occasional delivery man) is treated the same as a large slaughterhouse or pharmacy chain. Is there really a “grave danger” necessitating an onerous, emergency federal mandate at Dunder-Mifflin?

On the other hand, the rule exempts tens of millions of private sector workers who are independent contractors or who work at companies with fewer than 100 employees. (Given that the private workforce includes about 125 million Americans, an order that affects 80 million private sector workers necessarily omits about 45 million others.) OSHA rules typically apply to any company with more than 10 workers (though even the under-10 companies have to comply with some). Are these millions of workers not in “grave danger” too? The arbitrary 100-worker cutoff thus appears to be more about optics and resources than it is about actual public health. (Indeed, the threshold is especially arbitrary, given all the various ways—outsourcing, contracting, franchising, etc.—that businesses can fudge their numbers to get above or below 100 employees on paper.)

Other potential concerns—also to be determined once the ETS is issued—include whether the mandate will contain exceptions for workers claiming religious or other “personal beliefs” (as many state vaccine mandates do), working from home, or located in remote offices without much contact with fellow employees.

Implementation Concerns

Implementation of the ETS raises further problems. For starters, the order isn’t expected to be published in the Federal Register for several weeks and implemented a few days after that. Until then, employers are in the dark about the rule’s coverage, compliance, and enforcement, and then will have mere days to get into compliance. Indeed, Politico reported Monday that “Management-side attorneys say they are fielding frenzied calls from companies with questions over what the rules requiring them to verify that their workers are vaccinated or tested weekly for Covid-19 will actually entail and whether the business or unvaccinated employees will have to pay for the testing.” By the time the ETS and any resulting vaccinations take effect, moreover, the pressing Delta variant “emergency” allegedly necessitating this move may be over. (Let’s hope so.)

The mandate’s testing alternative presents another important implementation concern. As we discussed a few weeks ago, getting either a lab test or an at-home test remains difficult and costly in many parts of the country. The White House did announce efforts to improve this issue, including an agreement with Walmart, Kroger, and Amazon to discount self-tests, but as of my writing only Walmart appears to have these tests readily available (though for in-store pickup only). Kroger was out, and Amazon could deliver a $35 Ellume test in early October. Pharmacies near me are also running low, and I struggled to find a nearby lab test appointment. (Local news reports that these tests can run more than $200 a pop.) And this is all before a nationwide testing mandate goes into effect for millions of people. Thus, barring a major supply improvement, the ETS’ testing “alternative” will be more theoretical than practical (and its vaccine mandate more onerous).

These issues are, however, just the tip of the implementation iceberg, as National Review’s Phil Klein lays out:

[B]usinesses will now have to set up a system for monitoring who has been vaccinated and who has not. They will also have to facilitate weekly testing for those who choose not to be vaccinated, and keep track of the negative tests. Who pays for the tests? What happens in the time that workers are waiting test results? ….

Also, what are businesses supposed to do with employees who refuse to get vaccinated and won’t submit to weekly testing? Can they fire those workers? Are they forced to fire those workers?

To take things a step further, how does OSHA intend to enforce this law? Will businesses be forced to submit weekly reports showing that all their workers are vaccinated or have tested negative? Will OSHA officials do spot checks at offices to make sure that businesses can produce records demonstrating that they are in compliance?

And what happens if the federal government comes around to the view that booster shots are required, either in response to new variants or because of waning immunity over time? Will somebody who was considered fully vaccinated at one point still be considered fully vaccinated?

Apparently, the federal government is struggling with many of these same issues with its own vaccinate/test mandate, and it’s several weeks old. I guess we’ll just have to wait to find out how private businesses handle it—eventually.

Unintended Consequences

Finally, the ETS could have unintended negative consequences. Most notably, it might actually slow down vaccine uptake for at least three reasons:

-

First, as Singer worries, the federal mandate could embolden vaccine skeptics and cause many of them to “to dig in harder and seek relief in the burgeoning black market in CDC vaccination cards.” Many of those folks were probably never going to get vaccinated anyway, but they can influence fence-sitters in the same social circles (which is important for vaccine uptake). And, as Reason’s Robby Soave notes, now hardcore antivaxxers have “proof” that “the vaccines have less to do with their health and more to do with social control.”

-

Second, the mandate could turn some heretofore vaccine allies—especially in conservative or libertarian circles—into agnostic nonparticipants or even adversaries. Shortly after the news, for example, reasonable righty wonk Robert VerBruggen joked, “How do I unvaccinate myself as an act of civil disobedience.” To the extent that significant shares of holdouts are on the right, alienating conservative pro-vax allies (who, unlike Biden, might be able to reach conservative holdouts) seems like a bad idea.

-

Third, the mandate might slow down private employer mandates, which were just ramping up in the wake of the Pfizer jab’s full FDA approval, because covered firms must await the new OSHA rules and costs. As one corporate lawyer told Politico, “What we have right now is chaos… because of the unintended consequences of making such an announcement where there is no clarity with respect to a gargantuan number of questions that have been left open.” Another lawyer with experience implementing a company-wide testing system said that getting one up and running will cost “millions of dollars a year to any size company” because “it’s incredibly burdensome and time consuming and may not even guarantee health and safety in the way that mandating vaccines would.”

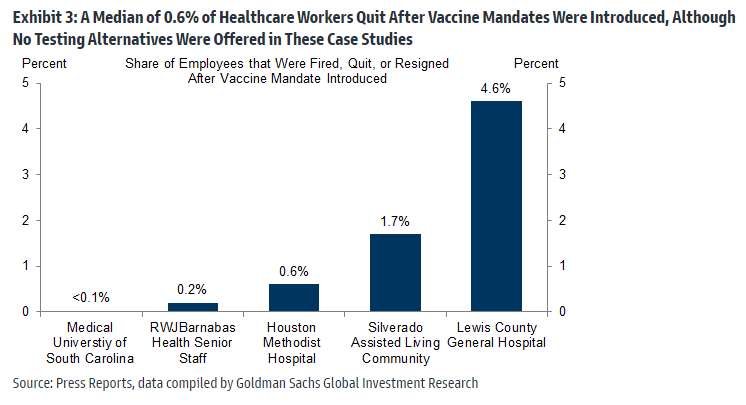

Furthermore, while most assume that the OSHA mandate would boost the Delta-staggered U.S. economy, it could have some economic downsides too (beyond imposing major new costs on numerous U.S. employers). For example, the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey indicates that significant percentages (20 to 30 percent) of adults still out of the labor force are unvaccinated. While the ETS could encourage some workers to rejoin the workforce (as their virus fears abate), it could encourage others to stay home or encourage employers to try to avoid hiring them. Large employers might also struggle to retain some employees, especially in places where vaccination is stigmatized and labor markets are tight. According to that Goldman analysis, for example, survey responses indicated that millions of the unvaccinated workers affected by Biden’s mandate say they’d rather quit than get the vaccine. A lot of that is probably exaggerated bravado, but Goldman provides several examples of unvaccinated health care workers walking out of their jobs in protest:

This risk is uncertain but shouldn’t be ignored given where the labor market is right now, how ingrained vaccine opposition (unfortunately) is in some places, and how many millions of eager-to-hire small business and other employment alternatives—exempt from the forthcoming OSHA mandate—exist.

(As an aside, it’s kinda funny/sad that many of the same folks cheering Biden’s OSHA mandate have also been cheering the “labor shortage” that could undermine it.)

Finally, there may be unintended social and cultural ramifications. Most obviously, a broad federal mandate risks further political polarization, especially as politicians and pundits in red states see political value in attacking Biden’s federal “overreach.” (Many pols are predictably fundraising off the announcement.) Of course, in many states these same folks have been the aggressor when it comes to pushing their own versions of hysteria and government overreach (e.g., trying to ban private vaccine mandates), but they now have even more cover—and they might be joined by others who had thus far toed a more moderate or non-interventionist line (e.g., South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem, who has taken flak for not backing a ban on private mandates). Furthermore, because vaccine holdouts in many states disproportionately are minorities or live in poor areas without good access to vaccines and testing, the OSHA mandate could ultimately discourage employers from hiring these workers or locating their businesses in those areas. (It’s not just going to punish your personal political enemies!)

Not all of these and other “unseen” effects are certain to happen, of course, but they should be considered against the obvious “seen” benefits of additional vaccinations.

Principled Concerns

Finally, there are principled reasons to question the proposed order for those of us who value liberty and limited government. In general, a commitment to freedom of association, property rights, and freedom of contract can (and in my personal view should) support private companies’ decision to condition employment or service on vaccination status, and the state shouldn’t therefore interfere in those transactions. Similar considerations tend to apply when the government acts as an employer or contractor. At the same time, however, libertarians have long debated government requirements that private individuals and businesses be vaccinated, and the issue raises complicated considerations regarding individuals’ rights and the role of government (see, for example, this Reason debate or this recent op-ed by Cato’s Robert Levy).

In this particular case, however, the issue seems much easier, given (1) who’s doing the mandating and how it came about (defying, for example, both separation of powers and federalism, while arbitrarily compelling select private businesses/workers and potentially empowering an army of new OSHA “vax cops” or whatever); (2) the dangerous precedent that a broad, unilateral ETS power could set (emboldening future presidents to take similar “emergency” actions); and (3) the mandate’s potentiallypolitical, rather than substantive, motivations.

In this regard, it’s important to note that the proposed ETS is not—as some have condescendingly claimed—par for the course in the United States. Sure, government vaccine mandates have existed here for centuries, but they have historically applied (1) to government workers (e.g., soldiers) or facilities (e.g., schools); (2) at the state or local level (where, as Shapiro notes above, there is a broader police/public health power); (3) to entities or individuals with a clear public health connection (e.g., hospitals) or who lack the agency or ability to mitigate the danger at issue (e.g., children); (4) as a condition to receive some sort of government benefit (e.g., a contract or visa); and/or (5) pursuant to formal legislation or (at least) rulemaking. Here, by contrast, we have an emergency, unilateral, federal mandate for every large U.S. business (regardless of its public health risk or connection to the government) to protect all workers (regardless of their health, location, or work status) from a “grave danger” that they can readily mitigate themselves. Throw in the continued availability of alternatives to federal coercion—including not just federal payments, which new research shows can be quite effective, but state and private actions too—and the proposed ETS would needlessly break new and troubling ground.

Summing It All Up

The last two months of Delta Variant Drama and its related life-altering effects have been particularly rough for this eternal optimist, strong believer in personal responsibility, and massive covid vaccine fanboi. It’s totally reasonable, I think, to wish more people were vaccinated and to get upset or depressed at those folks unwilling to do so. But just because something should be done doesn’t mean a federal government of finite, enumerated powers can or should be the one to do it—and especially not by a messy, emergency, unilateral decree:

I wish everyone would get vaccinated—really I do—and you’d blush if you heard some of the things I’ve yelled at my TV over the last couple months. But there must be limits to even the best intentions in even the worst times, and President Biden has in my view exceeded those limits significantly. Maybe that’s why even some Biden’s supporters are already claiming that he doesn’t really intend to implement the mandate.

I hope they’re right.

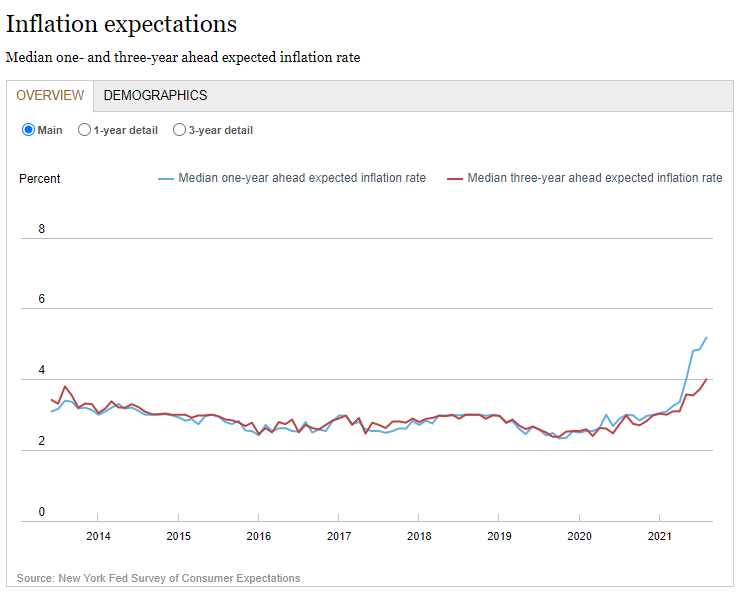

Chart(s) of the Week

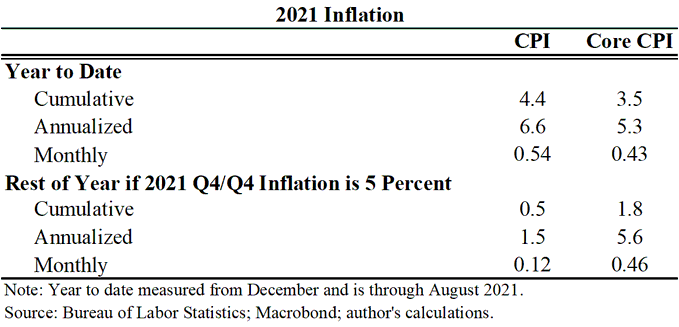

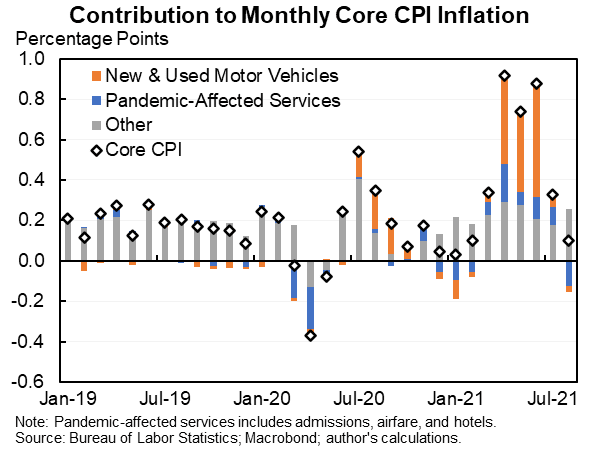

Things are getting frothier … (but the longer-term outlook’s still not clear).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.