Dear Capitolisters,

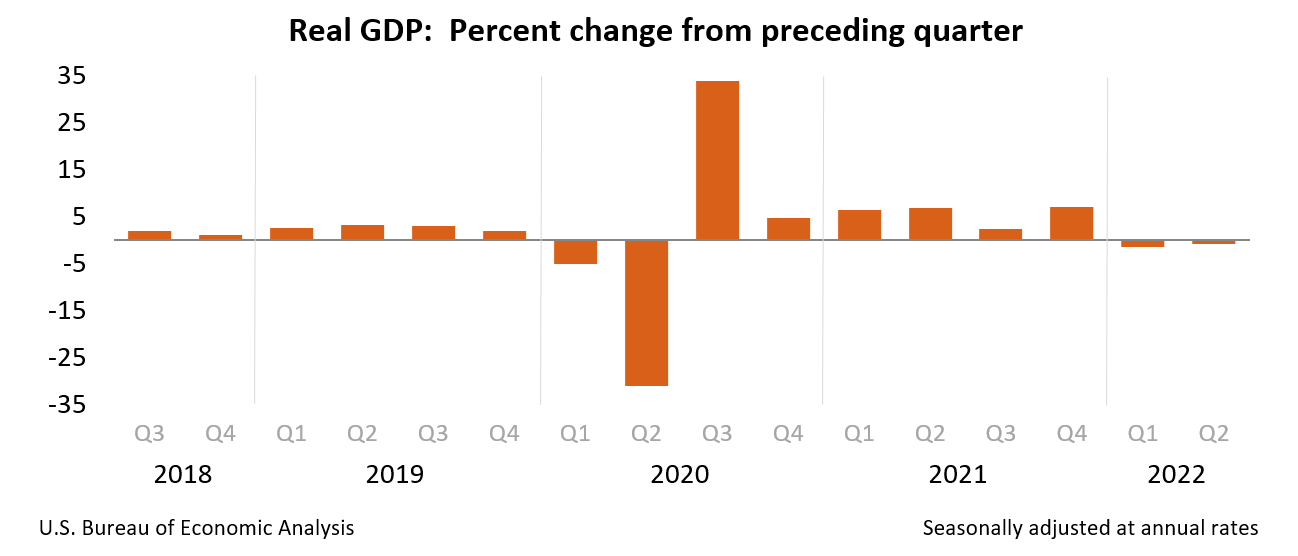

While I was (responsibly) sipping daytime micheladas last week, the interwebs exploded with a heated and mostly partisan debate about whether—after the latest real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product figures showed a second consecutive quarterly decline—the country is now in a “recession.”

For Team Recession (primarily manned by the Republican/right), the argument was that two straight quarters of GDP contraction is, while imperfect, the longstanding shorthand for determining a recession—one that Democrats themselves have often used before doing so became politically uncomfortable. On the other hand, Team Not Recession (featuring mostly Democrats/lefties) countered that the “official definition” of a recession—traditionally assessed by Business Cycle Dating Committee of the academic National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)—uses a wide range of economic data, including several indicators (most notably employment) that continue to show robust expansion. Both teams then yelled at each other for days; the White House held a big press conference; and folks even started fighting over the Wikipedia entry and related “fact-checks”—as American political debates so often do these days (sigh).

That debate is, as we’ll discuss, honestly pretty silly. But it does offer a good opportunity to talk about recessions, the GDP calculation, the current state of the U.S. economy, and what policymakers should be focusing on right now.

(Spoiler: not the definition of “recession.”)

Who’s Right?

At the risk of upsetting everyone (but when has that ever stopped libertarians?), both teams have a point. For Team Recession, economic historian Phil Magness took to the Wall Street Journal to summarize the case for why the “two-quarters rule” should apply:

Economists have long defined a recession as “a period in which real GDP declines for at least two consecutive quarters,” to quote the popular economics textbook by Nobel laureates Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus. This definition isn’t perfect, but it describes almost every downturn since World War II. …

There is no federal statute that appoints the NBER as the official arbiter of recessions. Quite the contrary, the federal government has historically followed the conventional textbook definition. The Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act of 1985, which attempted to rein in the deficit by triggering mandatory sequestrations in federal agencies, introduced a recessionary escape clause for tough economic times. If the Congressional Budget Office projected a recession, Congress could fast-track a vote to suspend the sequestrations. The law defined a recession as a period when “real economic growth is projected or estimated to be less than zero with respect to each of any two consecutive quarters.” The CBO could also trigger a suspension for “low growth” if the change in GDP dropped below 1% for two quarters.

Although the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act succumbed long ago to the profligate pressures of deficit spending, its “two consecutive quarters” standard may be the closest thing to an official definition of recession. Derivative language still appears in the federal statute books, and it has long been used as a basis for other counter-recessionary measures governing federal employment. Canada and the U.K. also employ the two-quarter definition to designate the onset of a technical recession, further attesting to its legitimacy.

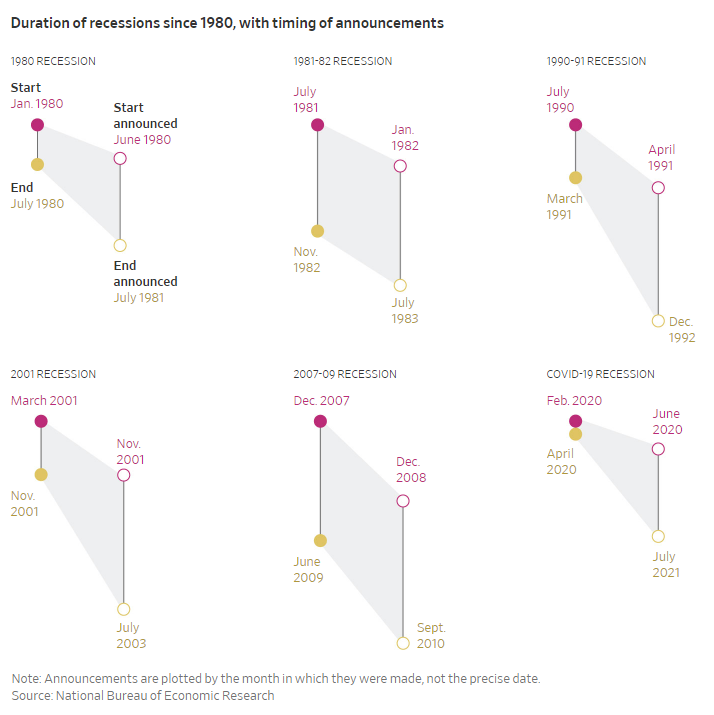

Magness adds, quite correctly, that the NBER approach “isn’t suitable for real-time policy determinations” because it can take months for the committee to make its call, as this recent Wall Street Journal primer and accompanying chart helpfully demonstrate:

In sum, there’s no quick, easy, or official “definition” of a recession, but two quarters of negative GDP growth is a pretty good shorthand that’s been widely used in the past, including in economics textbooks and U.S. statutes. Harvard/AEI economist Robert Barro echoed many of these same arguments earlier this week. And, of course, there are other economic indicators that are also flashing red these days—beyond the still-bad inflation numbers, we’re also seeing negative hourly earnings (inflation-adjusted), abysmal consumer sentiment, declining consumer confidence, flat real consumer spending, and an inverted “yield curve” (which plots the return on Treasury securities and goes negative during or right before a recession). And, as Reason’s Eric Boehm notes, most Americans now think we’re in a recession—which can itself fuel slower economic growth (that’s, like, pretty deep, man). So, recession it is, right?

Not so fast.

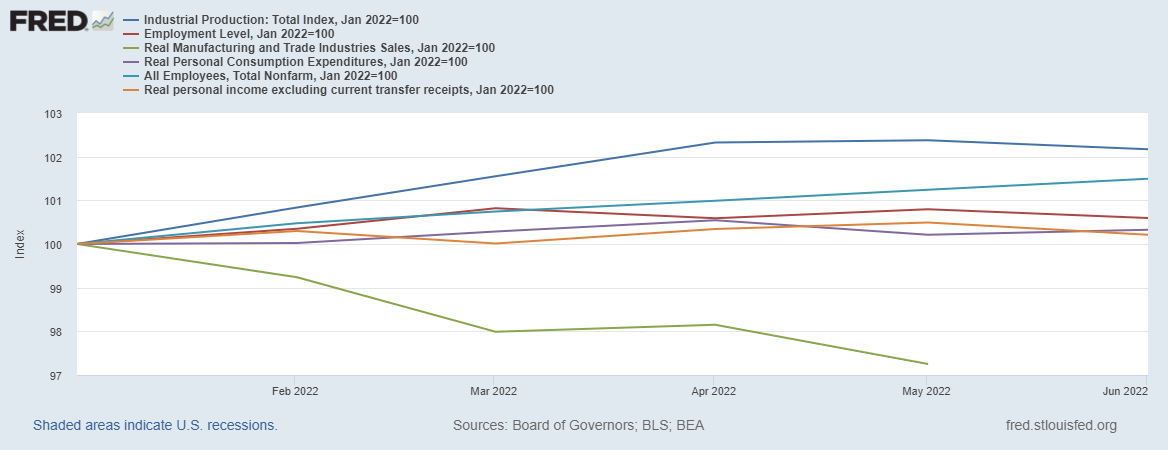

Team Not Recession also has a lot of valid points. Not among them, however, is the Biden administration’s claim that only the NBER’s “official” call matters. (That’s fine for academic purposes, but Magness and others are right that it takes months and is thus useless for determining policy today or tomorrow.) Instead, their best argument is with the current economic data—including but not only the indicators used by the NBER to (eventually) determine a recession:

As you can see from the chart above, the monthly measures of income, consumption, employment, sales, and production that NBER examines are—except for manufacturing and trade sales—still above 100, meaning that they were higher at end-June 2022 than they were to start the year. There are some warning signs in there, but there are also some robust expansions.

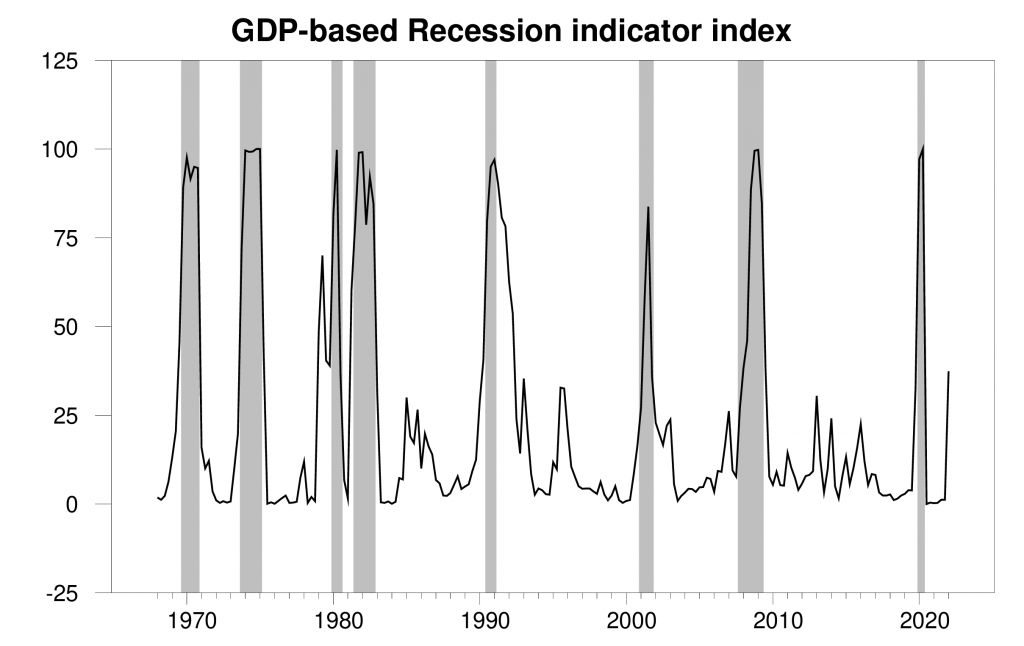

Other indicators of economic activity deliver a similar message. The guys at Econbrowser, for example, have developed a “recession indicator index” based on the same data the GDP calculation uses, and they’ve successfully called recessions for the last 17 years when the index rises above 65 percent. It’s only at 37.4 percent right now, though it’s also “flashing a clear warning sign”:

They also cite other positive data, such as the still steadily low unemployment rate (3.6 percent), still-positive GDP growth over the last 12 months, and separate measures of national economic activity (“gross domestic output”) and state-level activity (the Philadelphia Fed’s “coincident index”):

New data on manufacturing activity also show continued (albeit decelerating) expansion—something that’s never happened in any past U.S. recession. The team at Goldman Sachs adds that corporate financial results are still pretty good too: “With nearly three-quarters of its market cap now reported, S&P 500 earnings have increased 9% year-on-year, 52% of reporters beat consensus expectations by 1 standard deviation, and revenues are growing in every sector. ….Credit market fundamentals are also reassuring: high-yield defaults are well below average, let alone levels typical of recession.”

These are all good signs that, headwinds notwithstanding, we’re not in a recession—yet.

For my money, however, probably the strongest argument against Team Recession’s position lies with the GDP calculation itself. For starters, the initial (“advance”) GDP report that just came out is usually revised—and sometimes a lot:

This history might be especially important when dealing with a negative second quarter GDP print of just 0.9 percent and a highly unusual “pandemic economy” that has featured tons of revisions to national economic data (because sampling techniques and seasonal adjustments weren’t designed for global pandemics). Indeed, research from the San Francisco Fed in 2020 shows that GDP revisions can be particularly large during times of economic turbulence. Maybe subsequent revisions to first and second quarter GDP data will show even bigger declines, but the advance figures’ historical imprecision nevertheless warrants caution.

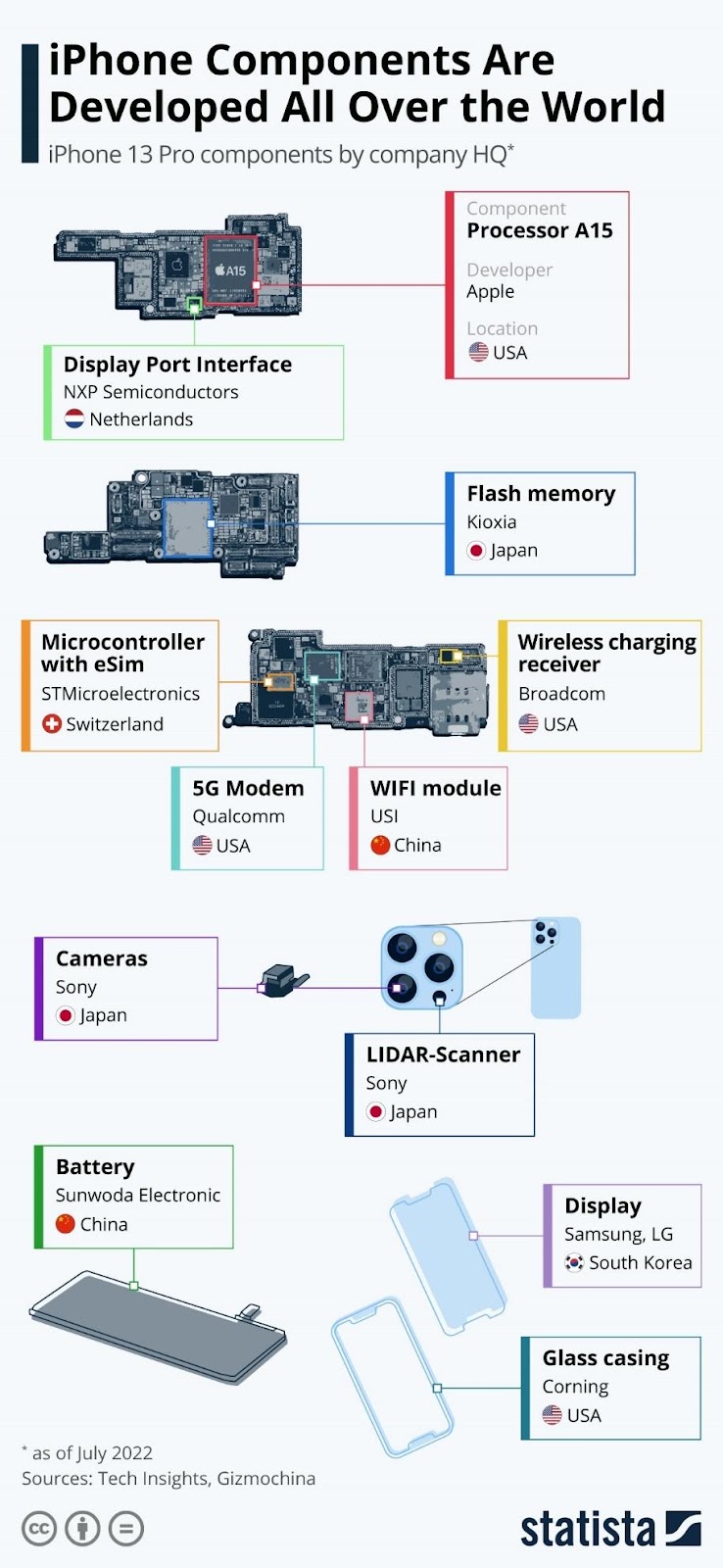

More important, however, is how GDP is calculated—a factor also exacerbated by the pandemic and now the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In particular, GDP is a clunky aggregation of several economic indicators: private consumption + gross private investment + government investment + government spending + net exports (exports—imports). Even in normal times, this calculation can lead to misleading conclusions about the U.S. economy. Economists in recent years, for example, have grappled with whether GDP captures real economic well-being or the substantial economic activity associated with “free” digital goods. And we at Cato have spent decades trying to explain (patiently—well, usually) that the GDP calculation’s mechanistic “net exports” element doesn’t mean that the trade deficit (aka “negative net exports”) actually causes U.S. economic growth to slow.

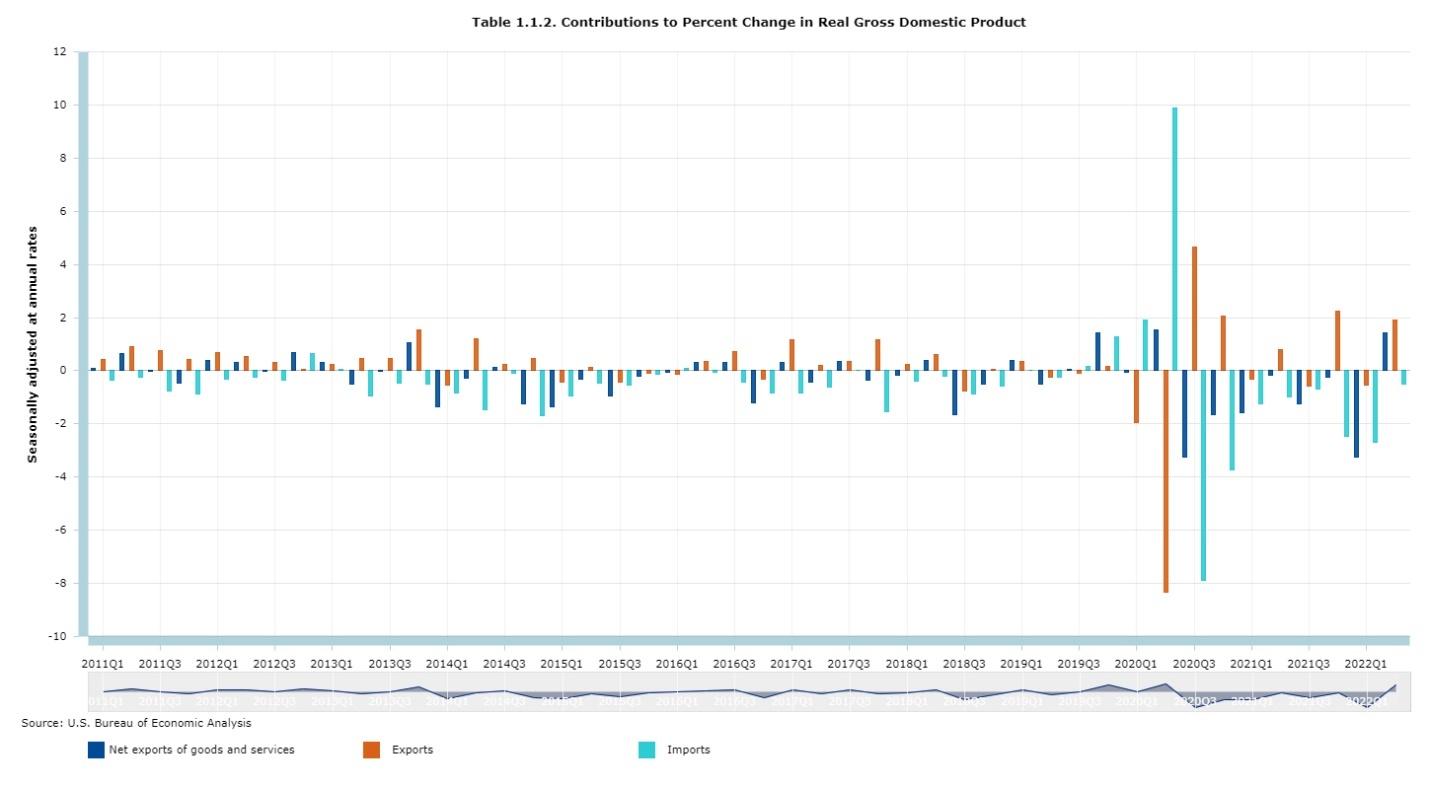

These calculation issues are especially problematic during the last biennium, during which certain GDP elements have swung wildly based on abrupt changes here and abroad. For example, an abnormally large “net exports” figure drove the first quarter’s negative GDP print, but—broader economic issues and conclusions aside—this number was caused mainly by the pandemic, not U.S. economic weakness. In particular, the U.S. economy was far more active and open (and thus voraciously consuming imports) than much of the rest of the world, especially locked-down China and suddenly reeling Europe. As a result, U.S. imports surged while U.S. exports shrank—and we got a historically large “net exports” number:

As the chart above shows, moreover, the pandemic has featured a lot of these wild trade swings, as compared to the previous decade. That volatility is a sure sign of economic uncertainty and pandemic-related changes to the global economy, but it says little about whether we’re in a recession. (Indeed, as the chart above shows, imports usually collapse during recessions—see the big teal peaks in Spring/Summer 2020.)

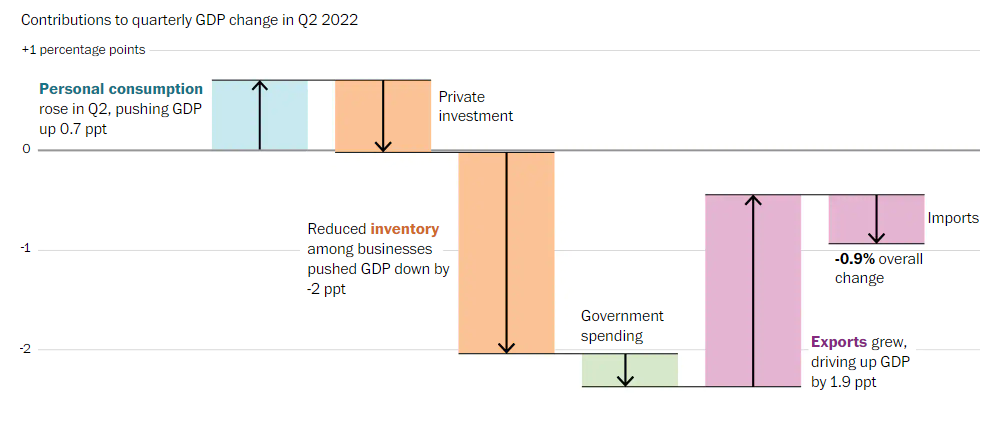

The second quarter featured similar irregularities with another volatile GDP component—inventories. In particular, a large reduction in U.S. companies’ inventories in the second quarter pulled down the “domestic investment” part of the GDP calculation:

But this again was mostly pandemic-related: As the Delta variant (remember that?) raged and supply chains improved, U.S. companies built up huge inventories in the fourth quarter of 2021 (thus contributing to that quarter’s surprisingly large GDP number), and they have been drawing down these supplies ever since (thus driving the second quarter’s negative number and contributing to the first quarter GDP decline too). That’s not a clear sign of economic weakness, and—as Pantheon Macroeconomics’ Ian Shephardson noted last week—might actually cause third quarter GDP to rebound strongly as companies restock for the fall.

In short, the two-quarters rule has been reliable in the past, but the pandemic and Russian invasion appear to have neutered it this time around. As Goldman notes, in fact, “the volatile imports and inventory categories that fully accounted for the GDP decline in the first two quarters of the year.” Some recession!

Who Cares?

As you can probably guess by now, I think Team Not Recession has the better of the policy arguments overall: The U.S. economy definitely has issues, but there are still a lot of positive indicators—some still quite robust (though others flashing warning signs). Given these issues with the GDP calculation and the questionable origins of the two-quarters rule, moreover, it seems wise to hold off on all the “recession” talk (for now) and maybe even to ditch that standard going forward.

But, really, this whole debate is silly: Unlike “inflation” or other key economic terms, there is no official definition of a “recession”—not in law and not even at the NBER (which kinda just assumed the title of “official recession arbiter” years ago). And key economic policymakers like Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell are focusing on the underlying economic data, not whether some combination thereof has magically unlocked a certain term that changes the course of the U.S. economy. I mean, it’s not like white smoke starts billowing from the Eccles Building, Powell emerges to declare —Michael Scott-style—that we’re in a recession, and U.S. economic policy suddenly changes.

Though that would be kinda cool.

The nerds’ approach, of course, is what they should do: whether we were in a “technical recession” (or whatever) last quarter or are in one right now tells us very little about what past economic policy has done and future policy should do. The data do—and right now, they’re not great but not terrible but pointing in an ominous direction in the future. And it’d be best for policymakers to just say that, not spend days debating what the meaning of “is” is.

Given all of these issues and the murkiness of the economic data, it’s unsurprising that most of the “recession” debate came from the political sphere—where silly economic arguments not only live but thrive, and where both parties are now gearing up for the November midterms. Their focus, in my view, is misguided for several reasons. Strategically, both sides take on unnecessary risks by vocally latching on to their preferred definition of a recession. (What if GDP is revised or bounces back bigly right before the midterms? What if the NBER data worsen considerably? Etc etc.) The White House’s legwork, moreover, has probably initiated the good ol’ Streisand Effect, drawing even more attention to the “recession” stuff (and Dems’ hamfisted efforts to dictate the narrative).

Even more importantly, the debate has wasted a lot of precious time that would’ve been better spent on communicating our messy reality to the American public and on developing and implementing actual policy that might actually improve the U.S. economy’s questionable trajectory Most of the policy effort, for better or worse, rests with the Fed right now, but there still remain a handful of policies—mainly on loosening up the economy’s supply side and reducing uncertainty—that the White House and Congress could pursue to take some pressure off American consumers and companies.

Unfortunately, Biden and congressional Democrats don’t really appear too interested in doing any of that stuff. Indeed, the last week or so has featured even more near-term deficit spending (e.g., the $79 billion in semiconductor subsidies that just passed Congress and the frontloaded “Inflation Reduction Act” that promises tens of billions more before any major tax revenues arrive); even more supply side restrictions (e.g., “prevailing wage” rules tied to the chip subsidies or the IRA’s proposed electric vehicle protectionism); and even more economic uncertainty (e.g., how the IRA’s new corporate taxes would be calculated). None of that is good for a teetering, inflationary U.S. economy—regardless of what the legislation might be named.

And that, not the “recession,” is the economy’s real problem.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.