One month ago this Friday, the Dali cargo ship crashed into Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge, resulting in the bridge’s collapse and the tragic death of six people working on it. Given the stunning visuals and the unfortunate loss of life, the incident understandably captivated the nation for days. But it also spawned a litany of hand-wringing about widespread damage to our supposedly brittle, globalized economy.

The day after the accident, for example, the New York Times’ Peter Goodman proclaimed that the “wayward container ship” yet again “shows world trade’s fragility”—and thus serves as a highly visible example of “the pitfalls of relying on factories across oceans to supply everyday items like clothing and critical wares like medical devices.” His NYT colleague Paul Krugman was less hysterical but nevertheless wrote a week later that, “Supply chains are making me nervous again” and warned of broader economic harm. The Washington Post dinged the accident as a result and symbol of “rampant globalization” and openly worried about these disruptions causing “big problems” economically. These outlets certainly weren’t alone in their worry. And social media, as you can imagine, went even further.

In one respect, this consternation never made much sense. Sad as the incident may be, the Port of Baltimore is relatively small—just the 17th largest in the nation and significantly smaller than nearby ports in New York, Philadelphia, and Virginia. On the other hand, the port is economically significant in narrower ways: It is the nation’s 10th-largest port for dry bulk commodities, handles 28 percent of all U.S. coal exports, and ships the most automobiles in the United States (about 850,000 per year). If April 2023 numbers are any indication, the port’s closure cost it more than $6 billion in two-way trade this month alone.

That lost economic activity is of course bad for the Port of Baltimore and the many people and companies that directly rely on it. Rebuilding the Key Bridge, moreover, will certainly cost lots of time and money. However, a month later it’s increasingly clear that those dire warnings of broader economic doom were totally unjustified. If anything, this latest supply chain non-crisis is, like several others before it, a testament to the resiliency of our relatively open and dynamic global economy and the millions of people who participate in it every day.

And Then What Happened?

The warnings proved hollow because they assumed that the Port of Baltimore’s billions in economic activity would simply cease in the days and weeks following the bridge accident. Yet mere hours after the Key Bridge collapsed on March 26, shipping companies and supply chain professionals began adjusting their operations to minimize the disruption. The very next morning, for example, ships headed for Baltimore had already started to arrive at alternative ports along the eastern seaboard—ports that subsequently expanded hours and made other operational changes to accommodate the additional cargo (including for all those automobiles). So, while the pundits worried about the port closure’s economic impact and politicians held photo-ops days after the fact, the actual experts were unfazed mere hours later:

“Container shipping is resilient and supply chains are going to find a way to keep working and to keep those goods moving,” Emily Stausbøll, an analyst at Oslo-based shipping-analytics company Xeneta, said on Bloomberg TV. Big industry players ranging from port operators to parcel companies were already implementing their Plan Bs.

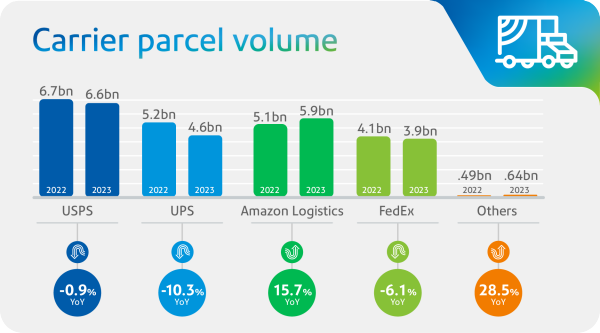

“Because we do have an end-to-end global supply chain, we can reroute products to different ports around the world,” United Parcel Service CEO Carol Tomé said in an interview on Bloomberg TV. “We can also move it off of the oceans and put it into the air. We’ll help reroute— we do this as a matter of course.”

Domestic rail lines, trucking companies, and other big players adjusted too. Many of them, in fact, were better able to respond more quickly to this latest supply chain problem because they’d learned from previous ones and modified their operations accordingly (e.g., by holding extra inventory or diversifying suppliers).

Their efforts weren’t driven by some altruistic desire to keep the U.S. economy humming but instead the good ol’ bottom line. One trucking company executive, recently recalled that “his port and logistics services team soon received a rush of calls and emails from frantic shippers seeking options to reroute freight away from the disaster area,” and—seeing an opportunity for new business (hooray, profit motive)—his staff sent its first of many “Navigating Port Disruption” email solicitations just a few hours after the incident. These folks and many others had businesses to run and customers to serve, so they didn’t just throw their hands up or wait weeks for emergency government grant money to arrive; they got to work.

As a result, the Baltimore accident was a momentary hiccup—a tragic one, of course—instead of a serious economic calamity. “Delays, congestion and diversions are occurring,” one recent dive noted, but—thanks to immediate changes by countless private actors—major disruptions have been minimized. “Supply chains,” the report added, “are showing their resiliency.”

Indeed.

Supply Chain Non-Crises Abound

As of this week, the Port of Baltimore has partially reopened, and officials plan to open a deeper channel tomorrow that “will allow most ships to transit to and from the port” (just as the president of DHL Supply Chain predicted on March 27, by the way). The bridge repairs will of course take longer, but for the most part, U.S. supply chains will return to their pre-accident normal in May.

The only remaining question, it seems, is whether anyone—especially those (perhaps gloating?) doomsayers—learn their lesson from just how well “the system” worked.

If recent experience is any indication, the answer is a resounding “no.” Since the pandemic, we have been repeatedly treated to dire—and since proven baseless—predictions of global economic doom because of regional disruptions’ effects on “fragile” global supply chains. As the Financial Times’ Alan Beatty reminded us last July, for example, worldwide “food crises” keep failing to materialize (fortunately) because of our relatively open and dynamic global economy (emphasis mine):

Readers will surely remember a surge of (well-founded) worry last spring and summer about a global food emergency. Lower grain exports from Ukraine, the oil and gas shock hitting energy-intensive agricultural production and transport, interruptions to global shipping, and general high inflation: it all added up. Moscow was weaponising grain by cutting off supply to world markets, potentially creating food crises in developing countries, especially in Africa. Then governments started restricting exports— India within weeks went from saying it would feed the world to blocking wheat exports— and a rerun of the 2007-08 food crisis seemed quite possible.

And then . . . basically nothing. Food prices fell. The export restrictions were lifted. It would be nice to think this was because governments and the World Trade Organization have got better at managing food trade and constraining export controls. In fact, it was mainly a series of good harvests and the trading system adapting to unreliable supply from Ukraine.

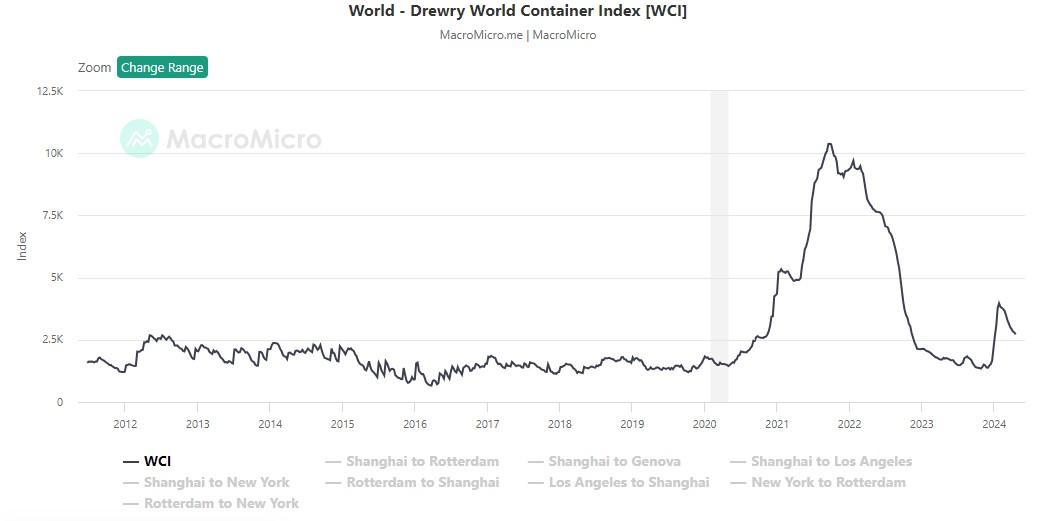

Supply chain non-crises weren’t just about good weather and a bountiful U.S. wheat harvest, either. Other problematic events have similarly failed to stop those “weak” and “vulnerable” supply chains. As we’ve discussed, neither the Ever Given debacle in the Suez Canal nor Russia’s weaponization of natural gas exports to Europe ended up causing long-term destruction. Droughts hitting the Mississippi River and the Panama Canal similarly failed to generate widespread problems and today are trending the opposite way. In January, the Houthis’ attacks on the Red Sea shipping vessels caused container shipping prices to spike and worries to rise, but now prices are falling again (just as supply chain experts at Flexport predicted). Inflation in Europe—contra the Houthi-related warnings this winter—continues to cool.

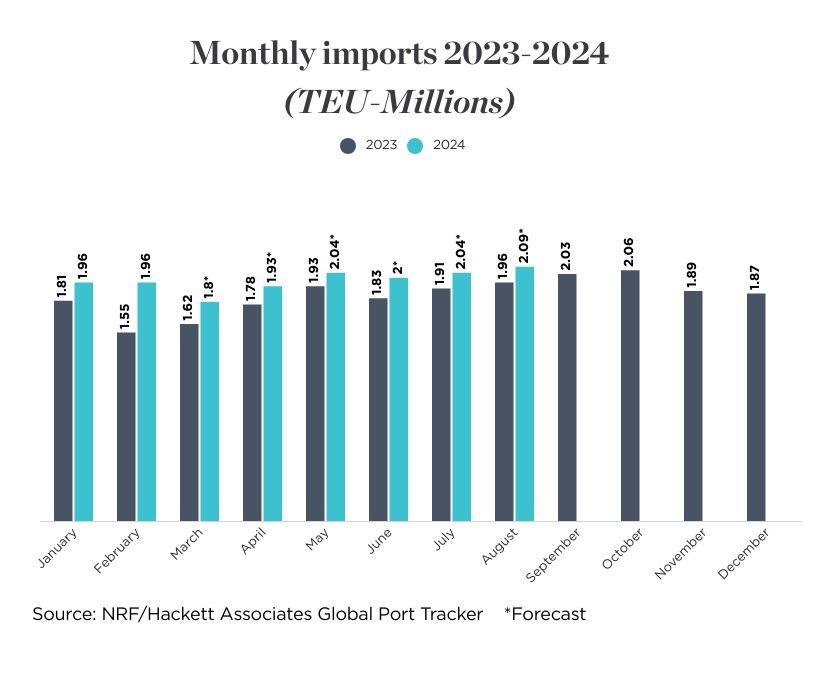

Time and time again, today’s “global supply chain crisis” is tomorrow’s forgotten birdcage lining. In fact, even after all the recent mayhem across the world, the National Retail Federation just reported that inbound cargo volume at the United States’ major container ports will top 2 million units in May (“the first time since last fall as imports grow despite new supply chain challenges”) and keep at that level through the summer:

Meanwhile, the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI), which incorporates several shipping and manufacturing metrics, remained in negative territory through March. Given the latest data and recent events, it seems likely to stay subdued in the months ahead.

Think Globally (and Dynamically)

So why do people keep getting this so wrong? Two big reasons, I think.

First, policymakers and pundits seem not to grasp just how uniquely catastrophic COVID-19 was for global supply chains (among other things). The pandemic didn’t just close a single port or sea lane or workforce or even nation but instead a large majority of them all at once. And after the initial shock, things reopened and closed and reopened again on different schedules, while consumers—still mostly stuck at home—had extra money (stimulus checks, savings, etc.) to spend on computers, furniture, and other heavily traded goods, instead of their usual services. Put it all together and throw in some bad government policy, and it’s a perfect storm for generational supply chain chaos. One-off events in specific places—or even a small handful simultaneously—just aren’t the same thing (thank goodness).

Second, and more importantly for our purposes, the politicians and commentators wailing about supply chain fragility fail to understand the speed and extent to which markets adjust in response to normal economic shocks. Writing last October about resilient commodities trade in the face of geopolitical turmoil, the FT’s Beattie provided another good historical example:

Even if commodity markets are politically bifurcated, simple supply and demand mean price increases from trade restrictions will create their own long-run solutions. Simon Evenett, who runs the Global Trade Alert project at the University of St Gallen in Switzerland, notes that rising output of rare earths minerals— though admittedly not the refined product— has reduced China’s ability to control global supply to its adversaries. In 2015, China produced more than 80 per cent of the world’s rare earths. By 2021, massive expansion in mining elsewhere, including the US and Australia, had pushed its share down to 58 per cent.

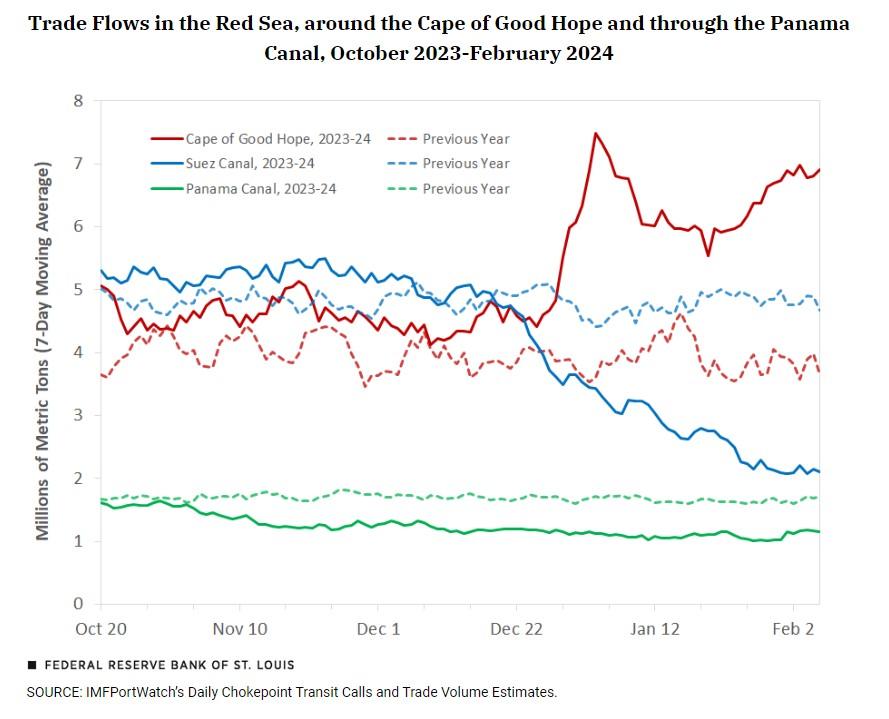

Today we’ve seen market participants—motivated by prices and profits—respond to shocks in Panama, the Middle East, and Baltimore, changing their operations to keep goods flowing and disruptions barely noticeable to you and me. When the Houthi attacks began, for example, global shipping companies started going around it and making other tweaks (cool map here) to keep goods flowing:

These and similar adjustments can mean longer routes, delayed shipments, and higher prices. But, as (mildly) annoying as those things may be, they too—pace Beattie above—offer valuable signals to market participants, pushing them to modify their future actions (e.g., shipping companies adding capacity in response to pandemic-era headaches) and thus make future disruptions even more manageable.

Occasional observers—especially ones who view economic activity as coming from the top-down instead of the bottom-up—don’t see this daily adjustment and thus expect the worst when problems inevitably arise. But, as my colleague Johan Norberg just described in a great new Cato video about his book, The Capitalist Manifesto, market actors are always thinking about this stuff. Thus, during the pandemic, it wasn’t nationalized supply chains (e.g., baby formula) that performed best but globalized ones: “Businesses and countries with complex supply chains … were used to thinking about options, investing in alternatives, and they could always find a producer in a place that wasn’t under lockdown at that particular moment.”

The stories above show that they did the same in response to the Baltimore accident.

As Norberg explained in the blog post accompanying his video, this constant, invisible market process means not only fuller store shelves over the short term but higher living standards over the long term:

Free market capitalism creates growth and innovation because it allows everyone to look for the places where the potential for it might be hiding. And since it relies on the vantage points and creativity of millions instead of a few people at the top, it is our best chance to find ways of adapting to and innovating our way out of unexpected crises, whether it is a pandemic, a war‐induced shortage or an environmental threat.

Norberg actually recorded his video last fall, before the Houthis and before Baltimore, but he’s been proven right yet again. That’s because Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” and Friedrich Hayek’s “spontaneous order” aren’t ideological catchphrases but fundamental truths we can see every day in real life—if we’re willing to look.

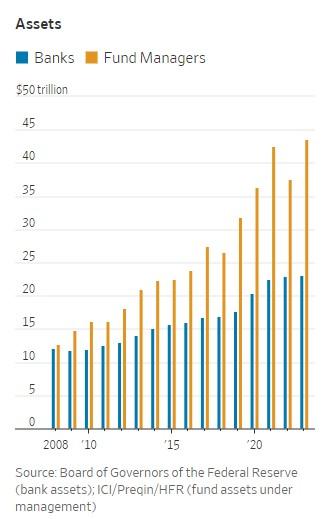

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.