A silly internet controversy (redundant, I know) recently erupted after Wendy’s CEO Kirk Tanner announced that the U.S. hamburger chain would experiment with “dynamic pricing” at some of its locations. For those unfamiliar, “dynamic pricing” simply means that, instead of remaining constant, a product’s price will occasionally change to reflect consumer demand—higher/lower prices in times of higher/lower demand. When Wendy’s plan was first announced, my immediate reaction was one of amused curiosity at the thought of cheap, off-peak burgers. But as news filtered down through the interwebs, populist outrage ensued. Leading the charge was Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who decried Wendy’s “price gouging” on Twitter. She was quickly outdone by her Senate colleague Bob Casey, who—in what must surely be the first ever official congressional letter to use the term “Baconator”—not only questioned the company’s “predatory and greedy” pricing plans but also demanded that Wendy’s answer a long list of questions about its business strategies.

As is often the case, Wendy’s quickly responded to these and other hysterics by clarifying that it wouldn’t soon be implementing burger surge pricing (or whatever) but would still try to increase pricing flexibility in the future. Now that the company is, happily I’m sure, out of the politicians’ crosshairs and back to selling (mediocre) hamburgers, we can all laugh at the entire mess. What we shouldn’t laugh at, however, is policymakers’ ever-increasing attention to meaningless stuff and the broader dangers this trend poses to the U.S. economy and the quality of federal governance.

Actually, Dynamic Pricing Is Good (and Common)

As my Cato colleague Ryan Bourne patiently explained last week, dynamic pricing—by conveying information to market participants and “smoothing consumption”—can benefit producers and consumers, even in places like restaurants that can’t (unlike ridesharing apps and their armies of price-sensitive drivers) immediately boost supply when consumer demand spikes and prices rise. In restaurants’ case, many consumers will avoid peak hours to enjoy lower prices during slower periods. Those that remain, meanwhile, will see better service—shorter lines, fresher food, cleaner facilities—during rush hour because there are now fewer people in the establishment. This can even mean lower prices overall, as compared to a fixed-price environment:

Dynamic pricing for some food outlets could make inventory management easier. For example, during off-peak hours, flash sales on meals could help sell items that would otherwise perish, thus minimizing waste and improving resource utilization. With fixed prices, firms can be left with surpluses or shortages if they misjudge demand levels. To avoid shortages, Wendy’s and others are likely to keep a buffer of stock. Managing this is likely to marginally raise prices for all consumers.

Coincidentally enough, a recent study on the use of dynamic pricing in grocery stores showed just these very benefits: Food waste went down, while both consumer surplus and profit margins went up:

I guess the populists must’ve missed it.

This doesn’t mean, of course, that it’d be smart for American fast-food chains to turn their outdoor signage into an ever-changing gas station pricing board. That’s because, Bourne notes, consumers also value certainty and can benefit from it by saving on so-called “search costs”: “If you turn up to Wendy’s and realize the price of a meal is higher than you’re willing to pay, you then have to go search to find food elsewhere.” However, we also end up paying for this convenience via both the aforementioned quality/price issues and our (very precious!) time:

If you go to Wendy’s at a packed time of day, you’re likely to be standing in line for longer waiting to order or pick up your food. The total “price” paid for the meal, inclusive of this cost, is thus higher than at off-peak times. We ration by more queuing, in other words, rather than price. Yet nobody captures this time payment.

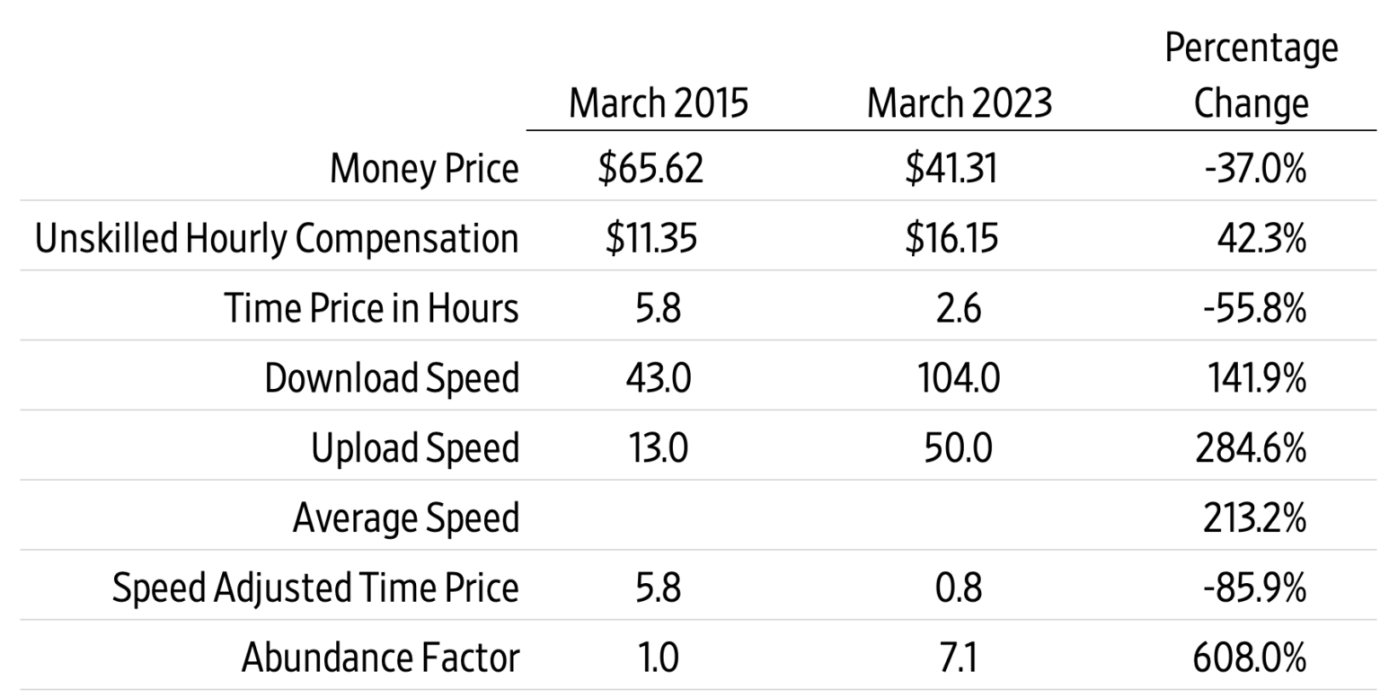

Dynamic pricing thus converts our time cost into a money cost—something we at Capitolism have been trying to explain to you people for years now (and yes, I’m looking at you, Steve Hayes).

It’s also something, as Doug Holtz-Eakin of the American Action Forum sarcastically reminds us, we utilize all the time:

There is a toll on my commute to work on I-66. But this weekend it was free. What is up with that? And when I checked on beach rentals, it turns out that right now the weekly rent is one-half of what I will pay next summer. The nerve! And what is up with happy hour drink prices? Stop it! When we went to the theater, matinee tickets were $2 less than the evening performance. Those bastards! Come to think of it, what is up with these senior citizen discounts? Just because I buy something at a different time in the life cycle, it is cheaper? What the hell is that? (Although, truth be told, just being eligible makes me angry!)

The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell confurs, highlighting other common examples of dynamic pricing, criticizing the populist outrage, and adding that Wendy’s biggest failure was likely in marketing, not economics:

Cutting prices during slower hours of the day is arithmetically identical to raising prices during busier periods. But for whatever reason, consumers seem more willing to stomach a “discounted” low-demand price rather than a “surged” high-demand price. They also get mad about some consumers being charged more, but they seem fine with price discrimination when framed as some consumers being charged less (senior discounts, student prices, etc.), as long as there’s some predictability to what prices will be for whom and when.

As she notes, Wendy’s competitors—some of whom also utilize dynamic pricing!—agree, and they quickly pounced on the company’s messaging error to remind consumers that they, dear customers, would never do such an evil, greedy thing.

It’s Not Just Wendy’s

Federal officials’ heightened interest in this type of “consumer protection” nitpicking is not, however, limited to a few meaningless (policy-wise) tweets and press releases from attention-hungry legislators. Instead, it’s become increasingly common for policymakers, especially on the left, to not only comment on meaningless consumer minutiae (see, e.g., this brand new example) but also try to regulate it.

Later this week, for example, President Joe Biden’s State of the Union address will almost certainly attack “junk fees” and tout his administration’s efforts to eliminate them. As Bourne has explained in a 2023 briefing paper, however, most of the fees added to our airfares, hotel rooms, and other services, while perhaps annoying, aren’t fraudulent or even deceptive; are fairly standard business practices (and relatively insignificant to companies’ bottom lines); and can benefit consumers. Airline fees are a perfect example that many of us have experienced firsthand. Last summer, in fact, I traveled to Colorado on a dirt-cheap plane ticket that limited me to a tiny carry-on backpack. That required some creative packing, sure, but I would’ve paid hundreds of dollars more to fly with another, supposedly more gracious, carrier. No, thanks.

The president’s regulation of bank overdraft fees (from January) and credit card late fees (from earlier this week) raise the same issues: Sure, those charges are irksome, but capping or eliminating them will end up hurting American consumers —particularly low-income ones—far more than it helps.

These fees are also often driven by government policy, not “greedflation” (or whatever). When Hawaii exempted amenities from its “transient accommodations tax,” for example, hotels responded with “resort fees” to lower their tax liabilities (and benefit consumers). A similar thing has happened with airline fees:

And, as my Cato colleague Nick Anthony reminds us, when Congress passed the Durbin Amendment, which restricted debit card fees that banks could charge to businesses, many banks responded by “replacing fees on debit cards with fees on bank accounts.”

There are also all sorts of market mechanisms—online reviews, third-party intermediaries (e.g., Google flights or Priceline), no-fee competitors (e.g., Southwest Airlines or many fintech firms), transparency-related companies (e.g., ResortFeeChecker.com), etc.—that can discourage the use of certain fees in most contexts. The idea that this is a huge problem requiring federal government intervention and lots of the president’s attention is, as Bourne rightly puts it in his paper, “bizarre.”

Then there’s the whole recent obsession with “shrinkflation”—another likely SOTU topic that annoys many people but the regulation of which makes no economic sense:

In the absence of shrinking the amount of product within a package, firms would have raised package prices even higher than they did. Banning “shrinkflation” is effectively a mandate to raise package prices, rather than pursuing a size‐price bundle that some (particularly low‐income) consumers might prefer. It would also encourage gaming, with firms no doubt launching new package sizes that they sell concurrently with existing sizes, before discontinuing the latter, leading to costly legal disputes.

The FTC’s current review of narrow food-related mergers is similarly silly. As Bloomberg’s Bobby Ghosh noted a couple weeks ago, for example, the agency has spent seven-plus months deciding whether to allow Campbell Soup, which makes Prego pasta sauce, to acquire Sovos Brands, which makes the tonier Rao’s. Not only is the merger small (only $2.7 billion in a U.S. economy that annually spends more than $1 trillion on groceries), but it would give the combined pasta sauce “monopoly” just 36.5 percent of the U.S. market, beating out the 22.9 percent share held by current top-dog Mizkan (which makes Ragu and Bertolli). Rao’s and Prego, moreover, don’t even compete against each other—the former is priced around three times as much as the latter—and, even in an absurd hypothetical future dominated by Big Sauce, alternatives exist and American consumers can always make their own. It’s really easy.

The same goes for the FTC’s investigation of Big Sandwich, i.e., the $10 billion acquisition of Subway by (ironically named) Roark Capital, which already owns Jimmy John’s, Arby’s, McAlister’s Deli, and Schlotzsky’s. As Jonah ably discussed late last year (encroaching on my turf in the process, grumble), the government’s case against this supposed “sandwich shop monopoly” falls apart once you consider the combined entity’s small share of your typical local (not national) sandwich market, how easy it is to enter that market (or to make lunch at home), or how sandwiches compete directly with plenty of other fast foods not owned by Roark Capital. Leaving aside the obvious entertainment value of having the federal government officially weigh in on the age-old internet debate over whether burgers, tacos, gyros and other bread/meat combinations are “sandwiches,” this—like the case against Big Sauce—is simply not something that requires the full force and attention of the federal government.

Yet here we are.

The Broader Faults

Beyond the issue-specific problems, all this picking of economic nits suffers from the same general ones, too—even leaving aside whether any of this stuff is remotely within the United States’ government’s enumerated constitutional powers.

For starters, the caterwauling isn’t just costless, inflation-related politicking (though it certainly is politicking). Bourne notes, for example, that populist attacks on routine pricing moves are “fueling legislative attempts to control firms’ prices or pricing structures” in ways that would generate real economic harms for companies, consumers, and the U.S. economy more broadly. Indeed, the press release accompanying Sen. Casey’s recent interrogation of Wendy’s cited that episode and “shrinkflation” as justifying disastrous federal price control legislation that he, Warren, and two other populist senators just introduced in Congress.

Groundless or insignificant regulatory actions, meanwhile, cost the companies involved millions of dollars in both legal fees and lost time. They also discourage these and other companies from exploring business innovations or transactions (e.g., mergers) that might generate substantial efficiencies or other economic benefits. And, as Adam J. White writes about the FTC, even if an agency ultimately loses in court, a broad and aggressive regulatory approach—and the chilling uncertainty it creates—teaches other powerful regulators “to rule beyond mere rules.” Given the open-ended state of U.S. law, that’s no small thing:

For agencies empowered to grant or withhold permits, licenses, and other ex ante approvals, the power of regulatory uncertainty is immense. From the FTC’s power over mergers, to the SEC’s power over new securities (as we are seeing in the debates over cryptocurrencies), to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s power over energy infrastructure, such agencies can accomplish much more—and with much less judicial review or political accountability—through regulatory uncertainty and deterrence than through the traditional forms of agency action.

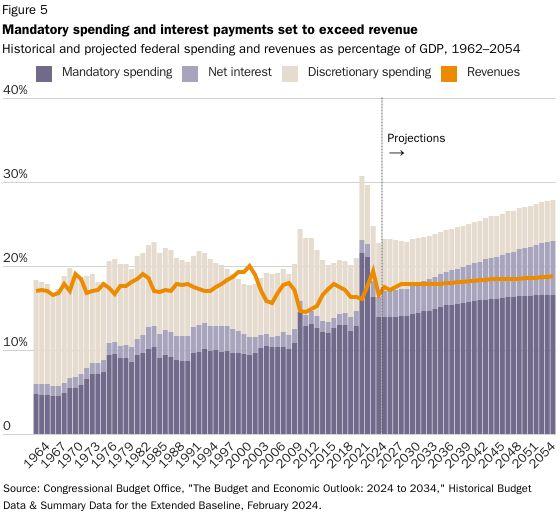

Frivolous government expeditions into lawful commercial transactions should even trouble those more inclined toward government action than a libertarian like me. That’s because government resources—money, manpower, time, attention, etc.—are finite, and the more of them the state spends scrutinizing spaghetti sauce or potato chip bags, or deciding whether a hamburger is indeed a sandwich, the fewer resources it has for more important and appropriate things (regardless of what you think those things are). Indeed, the same Politico article announcing this week’s creation of a new multi-agency pricing “strike force” (stop laughing!) notes that Congress will give the White House only about two-thirds of what it wants for antitrust enforcement. Budgets will get even tighter as some of those dollars are diverted to policing lawful annoyances.

Governments that try to do everything, moreover, usually end up doing nothing well—or, as Harvard’s left-leaning industrial policy fan Dani Rodrik recently put it, “The more things you try to achieve, the less likely you are to get them.” Indeed.

Finally, federal policymakers’ promises to “protect” us from resort fees, burger pricing, smaller cookies, or Big Sauce ignore the power and agency of consumers themselves. These things aren’t fraud or coercion; they’re just market behavior that politicians and many consumers don’t like. But that’s not a good justification for federal government action and, as Bourne explains regarding WendysGate, there’s plenty we can do about it. If consumers end up hating fast food surge pricing, for example, guess what happens next? Restaurants won’t offer it:

This is the virtue, in fact, of a competitive market economy. If consumers like the results of the price-quality bundles available to them under dynamic pricing, then that firm will make higher profits. But before Elizabeth Warren calls “gouging,” remember that this will encourage more firms to enter and compete against it with similar approaches. If customers utterly reject this pricing strategy, in contrast, then firms that adopt it will make losses. Other restaurants will be deterred from doing it. In reality, we’re likely to see different types of restaurants price in different ways to attract different types of customers.

The same principles apply to the other examples we’ve discussed (and many more). As long as markets remain open, regulatory barriers to entry remain low, and outright fraud is policed, consumers (and competitors and third parties responding to them) will punish the business decisions we don’t like and reward the ones we do. It happens every day—no big speeches, executive orders, federal “strike forces,” or new laws needed. Indeed, as we’ve already discussed regarding “greedflation,” another Biden target, there’s been ample evidence of this reality during our recent inflationary episode… and more evidence since then too:

The idea that we’re all helpless to fight back against routine, low-dollar commercial gripes simply doesn’t hold water. In fact, as the Wall Street Journal’s Josh Zumbrun reported last year with respect to “junk fees,” some U.S. companies have tried to eliminate last-minute add-ons and to be more up front and transparent about their prices—and consumers punished them for it. Academic studies show much the same. That preference might not be rational and might even cost us more money in the end, but, when it comes to many common business practices consumers supposedly hate, “we have mostly ourselves to blame.”

That conclusion, unfortunately, applies to our politics too.

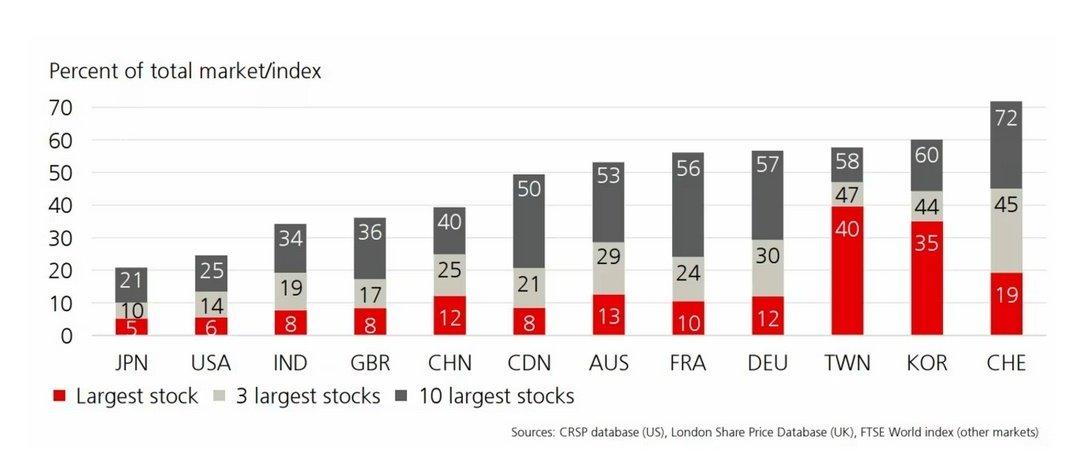

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.