Though the U.S. economy is still humming along (thanks in part to new immigrants), many in Washington are increasingly worried about waves of subsidy-fueled imports, particularly from China, swamping the U.S. manufacturing sector and thwarting the Biden administration’s grand industrial policy plans. In just the last few weeks, for example, we’ve seen U.S. officials warn of Chinese overcapacity and global gluts in lower-end (“legacy”) semiconductors, electric vehicles and parts, solar panels, and other goods. In the private sector, several manufacturing groups and unions have expressed similar concerns, with the United Steelworkers even requesting that the administration initiate a new “Section 301” investigation of Chinese shipbuilding subsidies. In most cases, the complainers’ solution to the purported problem is the same: more tariffs.

Leaving aside for a moment that at least some of these foreign subsidies have been driven by U.S. policy—especially our own subsidies, but also other things like export controls and tariffs—the subsidy/overcapacity issue is a real one, and not just in China. The last few years have seen an explosion in new government subsidies for state-preferred industries, and this “subsidies race” has undoubtedly boosted global manufacturing capacity for these products—regardless of actual demand for them. That last part is particularly important in China, whose leader Xi Jinping remains (bizarrely!) committed to pumping more cash into manufacturing even as the nation’s prolonged economic malaise dampens domestic consumption. The inevitable result is a lot of subsidized stuff piling up in the country with only one place left to go: overseas markets.

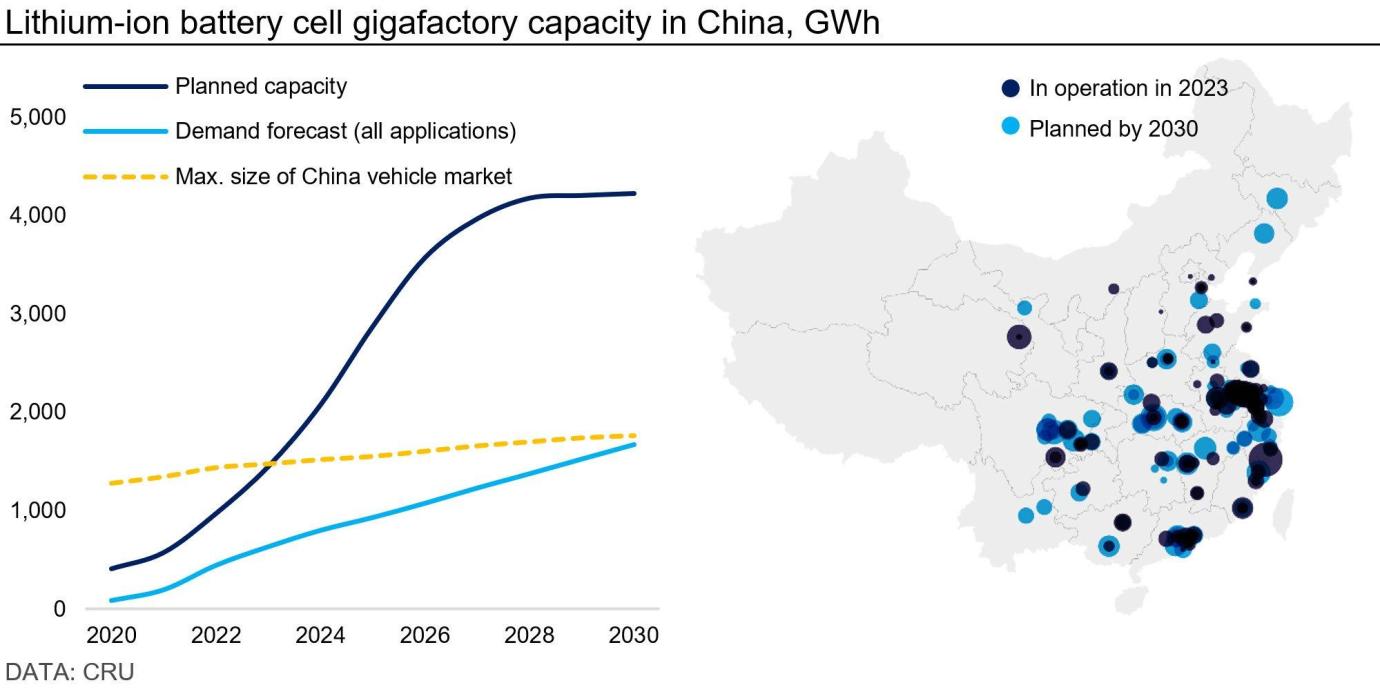

Here, for example, are EV batteries:

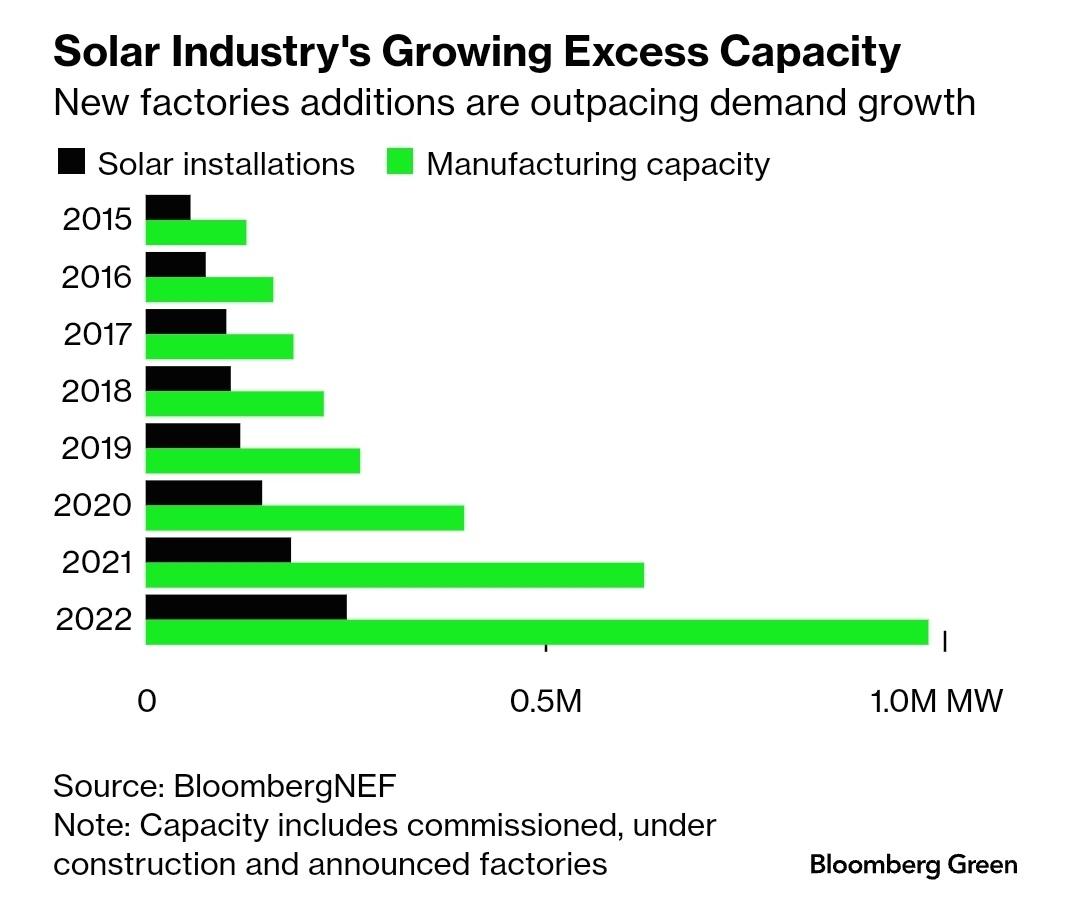

And here are solar panels:

So, we can all agree that there’s a lot of subsidized stuff floating out there or on the horizon, and that there are a lot of people—not just in the United States—worried about what comes next (and apparently unaware that this problematic result is a textbook industrial policy risk). The big question, however, is what to do next.

My preference might just surprise you.

A Strong Argument for Doing Nothing

From a purely free-market economic perspective, the ideal U.S. response to foreign government subsidies and subsidized imports is simple: do nothing. In fact, the United States should welcome other nations’ use of subsidies, particularly in the trade context, because those nations are effectively forcing their citizens to subsidize Americans’ consumption (which, as Adam Smith first explained hundreds of years ago in The Wealth of Nations, “is the sole end and purpose of all production”). As Milton Friedman and many other free marketers have explained, subsidized imports are essentially a form of foreign “philanthropy,” and if another government wants American citizens to enjoy its goods and services at artificially low prices, then—far from blocking said imports—Washington should tell them to bring it on.

Of course, subsidized imports can eventually displace U.S. production of those same goods or services, but—as George Mason University economist Don Boudreaux teaches with respect to the supposed threat of subsidized Chinese EVs—that’s not the end of the story:

It’s true that importing more EVs, whether subsidized or not, shrinks the portion of America’s industrial capacity devoted to producing EVs. And so it follows that importing fewer EVs enlarges the portion of America’s industrial capacity devoted to producing EVs. But it’s equally true that importing fewer EVs —and thus increasing EV production in the U.S.—shrinks the portion of America’s industrial capacity devoted to producing outputs other than EVs.

In other words, the U.S. economy can and would respond to Chinese EV subsidies by adjusting to produce other things that the Chinese aren’t subsidizing. In the medium to long term, in fact, the U.S. economy would come out ahead because the money American consumers saved on Chinese EV purchases (as compared to a more expensive alternative EV, regardless of where it’s made) would be invested or spent on other things—“extra” spending that would boost production and jobs in other U.S. industries, beyond what you’d see in a domestic market without those subsidized cars. This econ lesson isn’t as complicated as it sounds: If local gas station-owner Bob inherited a fortune and for some reason used it to sell $1/gallon fuel, he might put other local stations out of business, but the rest of us would save lots of money and use the savings to boost other local businesses (which could hire people who used to work at other gas stations). In the end, Bob would’ve effectively transferred his inheritance to you and me, gallon by cheap gallon.

Other factors reinforce the “do nothing” conclusion: First, and as we’ve repeatedly discussed, industrial and agricultural subsidies both here and abroad are expensive; often fail to achieve vibrant, globally competitive companies; usually do more economic harm than good overall; and are riddled with unintended consequences and cronyism. Whether in Europe, Asia, Latin America, or the United States, the subsidy successes are few and the subsidy failures are many—a lesson Japan Inc. learned 30 years ago and that China Inc. appears to be learning again today. Just because a government subsidizes a product doesn’t mean it’ll soon dominate the world—and often it’s just the opposite.

But, even if that product did end up dominating the U.S. and world markets, that’s not necessarily a good reason by itself for Washington to try to stop it. One could arguably imagine certain products directly connected to national defense that might require such government efforts, but few (if any) of the products today showered with global subsidies—and government condemnation—meet that criterion. Solar panels definitely don’t (they’ve been around for a century and are one of many forms of energy). Most semiconductors—especially low-value “legacy” ones—also don’t make the cut. Save a couple specialty grades, steel certainly doesn’t. And I’m still waiting for a compelling reason for why cheap EVs present such risks (regardless if Americans even want them!). It’s typically a lot of hand-waving about “floods” or “waves” of cheap stuff, with little additional explanation of why most of us—who neither work in nor live near affected U.S. factories—should care.

Even subsidies by bad actor nations don’t necessarily argue for a muscular unilateral U.S. response—beyond the aforementioned problems such subsidies often produce in the baddies’ home markets. For starters, it’s far from certain that such a government would actually want to cut us (i.e., its companies’ customers) off. According to a 2023 paper, in fact:

In general, the evidence to date does not suggest any strong dependence of the US on imports from non-friendly countries—on average—though there is dependence [in] some critical sectors. However, even in these sectors, the recent experience with COVID-19 suggests that countries regarded as non-friendly alleviated rather than caused critical bottlenecks.

It’s also uncertain that such a “non-friendly” nation or company could cut us off—at least not for long. As we discussed in 2022, concerns about “predatory” trade behavior are usually overblown: There are few if any real world examples of companies knocking out their competitors, establishing total market dominance, and then boosting prices or otherwise harming an importing nation and its consumers. The Bob example again comes in handy here: if he runs out of inheritance and suddenly jacks up gas prices to $10/gallon (what is this, California?), consumers will immediately start looking for alternatives and new competitors soon follow—as long as we let them.

China’s recent failed efforts to “weaponize globalization” show much the same.

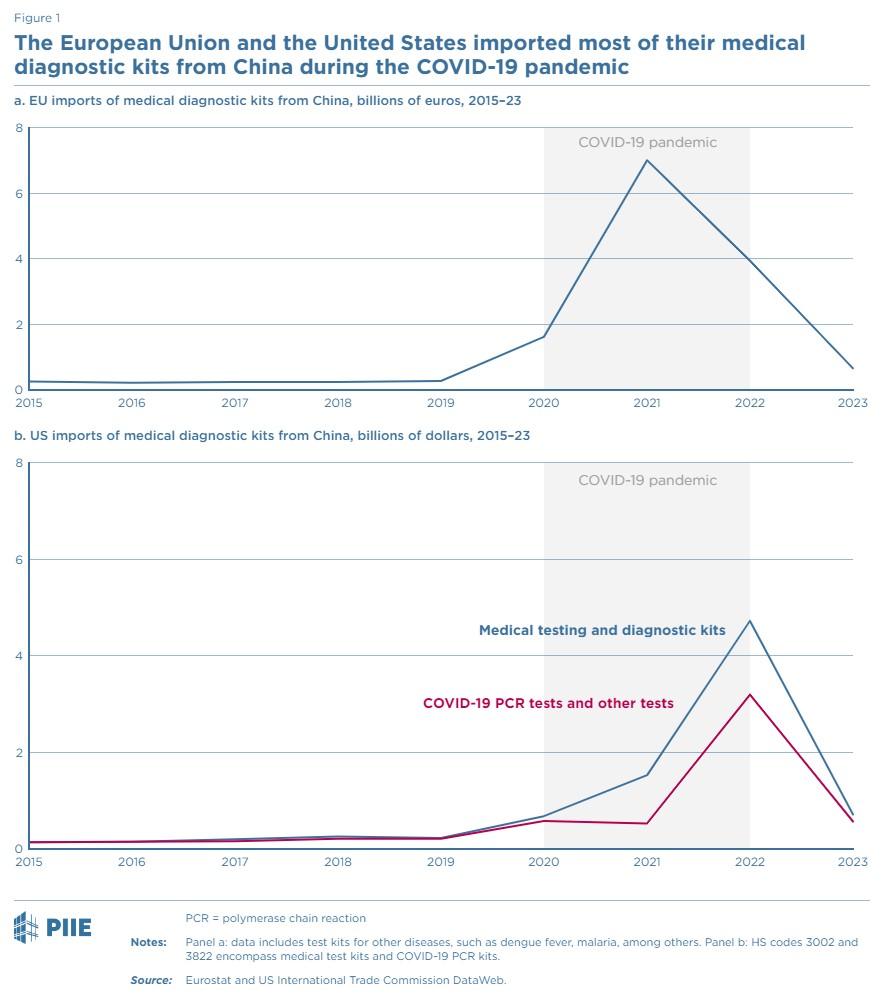

Indeed, the key to thwarting the predatory/weaponizing game plan isn’t tariffs or our own subsidies but simply for the U.S. market to remain open (locally and internationally) and dynamic so that we can quickly pivot to alternatives when a shock hits. We’ve discussed this over and over regarding all sorts of products, but a new Peterson Institute report shows it again for COVID-19 diagnostic tests: When the pandemic first broke out, the U.S. and EU imported tests from China, which got hit first and had preexisting test production capacity.

By mid-2021, however, the U.S. was producing its own tests and even exporting them to Europe, causing Chinese imports to decline. As PIIE notes, this transition was costly—U.S. tests cost nearly 100 times more than their Chinese equivalent—but it did happen.

Finally, Boudreaux and others are also right to note that, while foreign subsidies can cause short-term disruptions and long-term reductions in global welfare, U.S. tariffs or other government responses to those subsidies probably won’t fix the problem. Not only do tariffs often fail to produce a thriving industry, but unilateral retaliation also rarely induces foreign governments to change their behavior. And, of course, it’s quite likely that such retaliation, no matter now well-deserved, will fall victim to politics:

Home governments, after all, are subject to rent-seeking pressures just as are foreign governments. It is simply too tempting and too easy for a home government to falsely portray its own market-distorting policies—policies implemented for reasons no more noble than to create rents for powerful domestic producer groups—as being parts of a quest to cleanse the global economy (or at least the home economy) of subsidies and other market distortions introduced by dastardly foreign governments.

The Trump/Biden tariffs—regarding China, metals, and other goods—have demonstrated these facts yet again. Indeed, just this past week, U.S. solar panel manufacturers warned that all the tariffs and subsidies they’re already enjoying won’t be enough to stop cheap imports from China and other Asian countries:

I’m sure the next tariffs will, like, totally do the trick. (Sigh.)

But It’s Not Actually That Simple

While the economic case against blocking subsidized imports is strong, there are also strong grounds for mounting some sort of U.S. government response—grounds I laid out in a Cato paper on the subject more than a decade ago (i.e., the last time we had a global subsidy race). First, subsidies are harmful and should be discouraged:

Subsidies—particularly those targeting exports or specific sectors—distort markets and investment decisions. They lead to a misallocation of capital as resources are drawn to the production of goods and services that, but for the subsidy, would not otherwise be produced. In an increasingly integrated global economy of complex production and supply chains, national subsidies can have international implications. Moreover, targeted domestic subsidies act as a protectionist nontariff barrier by artificially lowering prices in the domestic market of the subsidizing government. Thus, efforts to discourage subsidies can promote global welfare.

Second, government-to-government negotiations to eliminate subsidies haven’t borne much fruit. After the Great Recession, for example, attempts within the G20 and elsewhere to get governments to commit to limit trade-distorting subsidies proved “only minimally effective, mainly as a check against serious backsliding rather than a strict prohibition or springboard for real reform.” Today, basically no government has responded to Chinese, U.S., and other subsidies with an invitation to negotiate a multilateral pullback.

Third and most important are the political economy considerations: Politicians and rent-seeking interest groups often use foreign subsidies to justify their own demands for U.S. subsidies or import protection—measures they claim are essential to offset the “unfair” advantages bestowed on subsidized foreign competition. Without some sort of U.S. government response to those foreign subsidies, the political case for subsidies, tariffs, and other bad policies is stronger (if not irresistible), regardless of the economics. Sugar is a classic example in this regard: Florida Sen. Marco Rubio has justified his vote to protect the U.S. sugar program on the grounds that it is necessary to counteract foreign subsidies, and the industry has said U.S. subsidies should go only when all foreign ones go, too. Given the U.S. sugar program’s many harms, this argument makes no rational sense—but it does seem to move the political needle.

Similarly, foreign subsidies can also undermine key interest groups’ support for freer trade policies, especially trade agreements. Implementing these deals depends in large part on balancing pro-trade exporting companies and farm groups—eager to find new markets abroad and thus to lobby for free trade agreements (FTAs)—against U.S. firms and workers worried about import competition (and thus lobbying against the FTA). However, if a company or farmer that supported a U.S. FTA with country X then faces a flood of X’s subsidized imports two years later without the U.S. government doing something about it, that company/farmer will probably be less likely to support the next FTA with country Y. So might other companies/farmers watching that situation play out.

Thus, “doing nothing” might make for great economics, but, thanks to politics, it could mean even worse policy in the future—and we have plenty of evidence in just that regard.

So, What to Do?

Believe it or not, I’m persuaded by the political economy responses to the classic, “do nothing” approach to foreign subsidies and wrote as much in that old paper. That doesn’t mean, however, that Trump-style tariffs or countersubsidies are the correct response, for many of the reasons that Boudreaux and others cite—especially these measures’ inefficacy and susceptibility to corruption.

Fortunately, we have a third choice: the global anti-subsidy disciplines set forth in the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement). All 164 WTO members, including the United States and China, have agreed to abide by the SCM Agreement’s rules, which are intended to encourage international trade by both preventing the proliferation of trade-distorting subsidies and providing reasonable dispute-settlement mechanisms for adjudicating subsidy-related disputes. The SCM Agreement 1) defines what is and isn’t a “subsidy”; 2) prohibits the most trade-distorting subsidies (those tied to exports or the recipients’ use of local content over imports); 3) lets a WTO member challenge other subsidies (i.e., ones that harm the member’s domestic companies at home or in overseas markets) at the WTO or via a “countervailing duty” (CVD) investigation; and 4) sets forth procedures for CVD cases.

(For the uninitiated: in a CVD case, a national government agency investigates, usually at the request of a domestic company or union, whether imports of a certain product have been subsidized by a foreign government and are causing injury to the domestic industry making the same product. If the agency finds both subsidization/injury, it can impose remedial duties on the imports that are intended to offset the subsidies and thus level the playing field in the home market.)

The SCM Agreement isn’t an outright ban on all subsidies. Instead, it reflects a compromise among all WTO members, discouraging only the most distortive government subsidies while allowing members to utilize broad-based subsidies and limiting the protectionist administration of CVD laws by overzealous government agencies running the investigations. The U.S. administration of its CVD cases has flaws—ones that have gotten worse in the last decade and reflect some of the concerns that “do nothing” folks have raised. Too often, CVD cases produce duties on imports in excess of the level of subsidies found—turning what are supposed to be remedial import taxes into punitive ones. More importantly, U.S. CVD law has no safety valve for suspending cases or duties that, while technically justified under WTO rules, undermine bigger national economic goals. In the last few years, for example, the U.S. has slapped CVDs on numerous renewable energy products and housing construction materials, even as the government tries to increase Americans’ access to those very things. Nevertheless, unlike the U.S. anti-dumping law (which targets private pricing behavior and is utterly detached from any legitimate purpose), the CVD law has a reasonable foundation and should thus probably be reformed instead of scrapped entirely.

That said, global anti-subsidy rules’ alternative process—a WTO dispute—is a much better approach than unilateral CVDs. Most importantly, WTO cases are adjudicated by respected independent arbiters approved by all WTO members. That makes decisions mostly immune to domestic politics (and politically motivated provisions of national CVD laws) and more respected by WTO members, including those on the losing end of a dispute. Thus, as we’ve discussed, WTO cases have been relatively effective in getting members—including the United States and China—to abandon their offending measures. Also, as trade law guru Simon Lester just explained, WTO anti-subsidy disputes have a broader reach than CVD cases: litigation can involve more than just two countries; cases examine trade effects in any global market, not merely the market of the complaining government; and the rules envision remedies beyond just more (MOAR!) tariffs, thus giving the complainant “a greater ability to induce changes to the subsidy measures.” They can even get resolved via government-to-government consultations that must occur before litigation even commences.

The WTO system isn’t perfect—it’s too slow, and some of its rules could stand to be updated—but it still provides a better approach for governments interested in actually resolving foreign subsidy and related problems, rather than just finding an excuse for enriching a few domestic interest groups (and hurting American consumers and the economy in the process).

Summing It All Up

Global subsidies are a problem—and one that, for well-founded political reasons, can argue for governments doing more than just the economically solid “nothing.” Tariffs and other unilateral measures, however, come with their own big concerns and thus can often be a cure that’s worse than the disease. Fortunately, WTO anti-subsidy rules and disputes provide a third choice that, while still imperfect, can better address global subsidies’ distortions while avoiding unilateral remedies’ own pitfalls.

National CVDs are one way to enforce these rules, and—thanks to procedural and substantive disciplines imposed on their use and the clear availability of judicial review (domestic or at the WTO)—they’re certainly better than the opaque lawlessness of current and likely future U.S. tariff policy. One cheer, therefore, for the EU’s new CVD investigation of Chinese EVs, especially since the EU’s anti-subsidy law, unlike the United States’, has a “public interest” check to ensure that new duties don’t undermine more important strategic, economic, or social objectives. It would’ve been better for the EU to have taken its Chinese EV gripe to the WTO, but at least it hasn’t gone Full Trump/Biden/United Steelworkers just yet.

In general, governments haven’t embraced the WTO alternative to domestic CVD cases, with the latter still far more common than the former. Some of that preference is the system’s fault (e.g., for being too slow), but most systemic problems can be fixed by relatively simple reforms (via negotiations). The WTO’s more intractable problem is the members themselves, particularly the United States, which continues to block not only new appointments to the WTO’s Appellate Body (thus crippling the dispute system) but also broader reform negotiations. In fact, the Biden administration recently doubled down on this position, started during the Trump years when it threatened to maintain its WTO blockades if the EU dared restart its challenge to (bogus) U.S. “national security” tariffs on European steel and aluminum.

Chinese subsidies might still be worse for the global economy than current U.S. trade policy, but not by much.

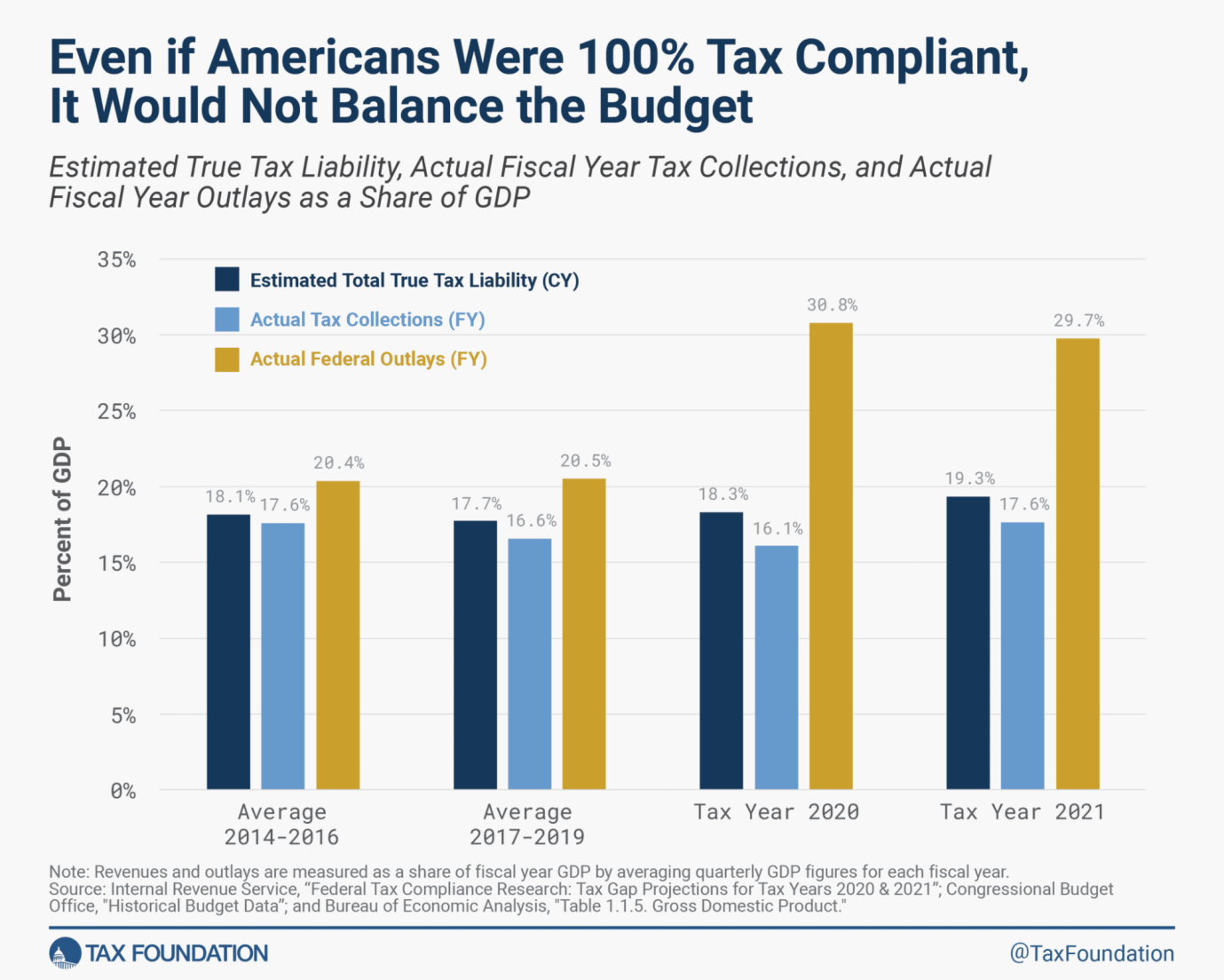

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.