It is easy to overinterpret election results. Back when I was researching my last book, I spent days running down a fascinating rabbit hole. I was trying to answer a key question: Why were partisans so oblivious to the escalating tensions that were tearing America apart? Why were they so confident that the solution to American polarization was domination and not accommodation?

The answer was clear. For decades, winners and losers alike spun virtually every American election as the sign of things to come, the harbinger of a permanent victory (or permanent defeat). You don’t even have to be that old to see the recent pattern. The thrill of Democratic victory in 1992 turned into the agony of defeat in 1994, then the thrill of victory again in 1996.

After an agonizing election loss in 2000, the Democrats were apoplectic after Bush won again in 2004. Remember the “United States of Canada” and “Jesusland” memes that swept the internet as progressives lamented the alleged rise of Christian dominionism?

Then Obama won in 2008. But for Republicans, that was an aberration—a fluke caused by the housing crash and an unpopular war. The real majority came to the polls in Tea Party 2010. But wait: Obama won again in 2012, and suddenly all the momentum was on the side of the “coalition of the ascendant.” Remember that phrase? It signaled permanent Republican doom—the alleged party of white people couldn’t possibly keep winning in a nation that was growing more diverse by the year, could it?

Then came 2016. The overreading began once again. The old electoral college “blue wall” had become a “red wall,” and Trump had supposedly unlocked the key to lasting control. But, well, you know the rest.

Everyone keeps looking for the political Battle of Yorktown—that moment when your opponents lose once and for all and they march out slowly before you while the band plays “The World Turned Upside Down.” Instead, in a closely-divided nation that’s characterized mainly by negative polarization and calcification, the better analogy is to trench warfare—grinding, bloody attrition, with gains often measured in yards rather than miles and true breakthroughs few and far between.

Thus, the question after any given election isn’t so much, “Who is ascendant?” Rather, it’s “In which direction did the lines move?”

And that question doesn’t just apply to the raw political results of any given election. It’s easy to see the shifting balance between red and blue in House and Senate charts, but often the more important cultural changes can be harder to discern. And in this instance one of those more important changes was the blow to the malice theory of American politics.

The malice theory is a core element of Trumpism, and it’s a natural temptation of negative polarization. Negative polarization (or negative partisanship), as I’ve written many times, is the term for politics that is fundamentally motivated by animosity for the other side more than affection to your own party’s leaders or ideas.

Under the malice theory, the key to electoral victory is unlocking that anger. That means highlighting everything wrong with your opponents. That means hyping their alleged mortal threat to the Republic. Because of pre-existing animosity, your message will fall on fertile soil.

In this context, it’s easy to see how kindness and graciousness are seen as weakness, or at least as a lack of conviction. After all, who should be kind to the “godless communist orcs” who are “trying to ruin this great country”?

Moreover, if your opponents are that bad, then persuasion is a waste of time. Defeating the enemy isn’t about persuading the enemy, but rather about mobilizing the righteous.

So you can see the obvious incentives. Decency contradicts the call to action by subtly undermining the idea that your political enemies are a mortal threat. Fear becomes a more powerful tool than inspiration. After all, inspiring people is hard. Scaring them is easy—especially when the internet gives you constant access to the worst and weirdest voices on the other side.

But here’s where the malice theory collides with human nature. Most people aren’t content with simply thinking their opponents are terrible. They still want to see themselves as good. They want to see the world as “good versus evil,” not “lesser evil versus evil.”

That’s why the argument that voters should always swallow deep moral objections to vote for the lesser evil are ultimately unsustainable. When confronted with relentless wrongdoing from your own partisans, one of two things happens—over time you’ll either redefine evil as good, or you’ll abandon evil for the good.

The first response is core to much of the MAGA movement. It’s how someone goes from holding their nose and voting for Trump in 2016 to being the first bass boat in the boat parade in 2020. We all watched it happen. How many friends and neighbors went from voting for Trump in spite of his flaws to loving him precisely because of who he was?

The ultimate expression of this faction was represented by what’s been called the “Stop the Steal” slate of Republican candidates. These were the folks who were all-in, not just on Trump, but on some of the most transparently, incandescently absurd political conspiracies in modern American history.

In their good versus evil paradigm, they believed Democrats were so malicious that they would, in fact, blatantly steal an American election, and it was thus good to fight the peaceful transfer of power, to deny election results, and even to excuse, rationalize, or minimize the violence of January 6.

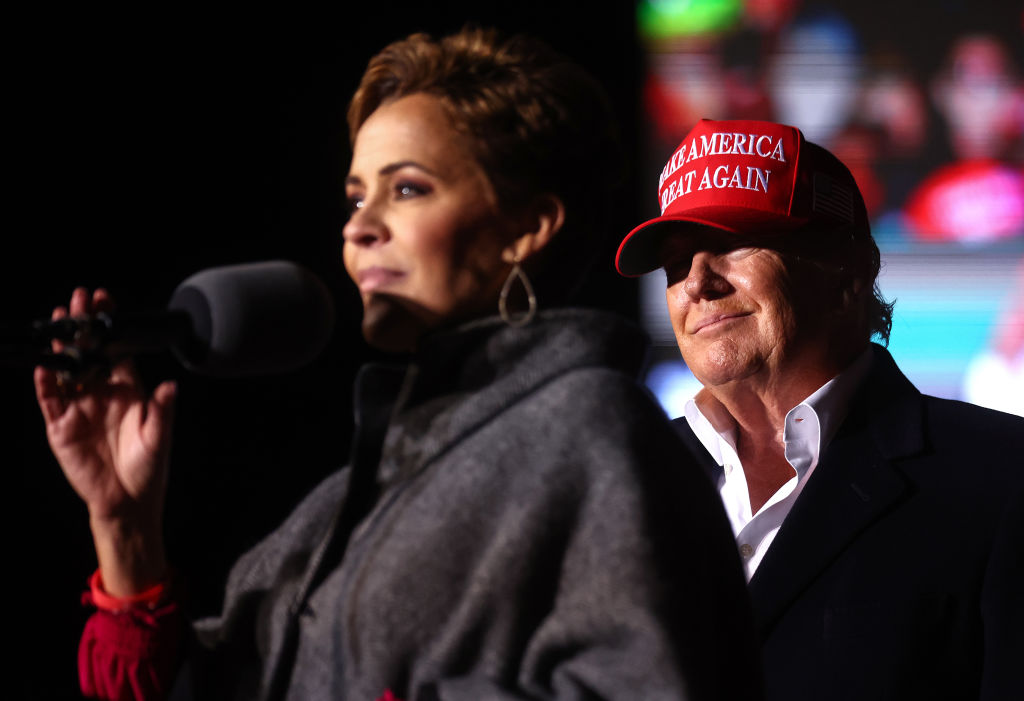

As of the time I type this newsletter, every single candidate from the “stop the steal” slate of MAGA secretary of state or gubernatorial candidates has lost their race, with one key exception—Kari Lake from Arizona. Lake is currently losing, but a number of Arizona political pros think she may still prevail.

Win or lose, her example is instructive. Her Republican predecessor is Doug Ducey. I know Gov. Ducey a little bit, and I know him to be a good man, and an effective governor. Earlier this year he signed into law one of the most expansive school choice programs in the country, a triumph for those of us who want to see children from poor and working-class families enjoy the privilege of making better educational choices for their kids, a privilege the wealthy have long taken for granted.

Ducey—like Georgia governor Brian Kemp—also withstood intense pressure from President Trump to reverse the results of the 2020 election and held firm. The Arizona GOP censured him for his stand and then nominated Lake, one of the most outspoken advocates of the stolen election theory in the United States.

Yet now she’s struggling. Ducey, by contrast, won re-election in 2018 (a Democratic wave year) by a whopping 14 points.

I don’t want to make the very mistake I identified at the start of this newsletter and overstate my case. Talk of a true MAGA “repudiation” is overblown, especially when Donald Trump is still expected to announce that he’s running again and when he’s still likely to start the race as the Republican frontrunner. Readers can point to any number of winning candidates in their states who revel in malice and who traffic in conspiracies.

But remember, the question isn’t whether anyone achieved ultimate victory or faced a final defeat. It’s in which direction the lines moved in our nation’s political trench warfare. And they most definitely moved back towards reason and our most basic moral norms.

I’ll share another example. Shortly after the vicious attack on Paul Pelosi, Republican Glenn Youngkin responded the same day of the attack by saying, “There’s no room for violence anywhere, but we’re going to send [Nancy] back to be with him in California.”

That statement wasn’t as bad as the mockery and conspiracies that we heard from the true MAGA right, but it was still wrong. It is not how a decent person responds to a terrifying attack. But Youngkin reversed course. He wrote a handwritten note to Nancy Pelosi, apologizing for his statement.

That simple act of humanity isn’t an act of weakness. It demonstrates strength of character to not just admit when you’re wrong but to make amends with the person you’ve harmed.

Days later, Youngkin found himself in yet another controversy, this one not of his making. The politics of malice asserted themselves yet again, when Trump lashed out at him on Truth Social with a bizarre post that claimed credit for Youngkin’s 2021 election. It started with this strange and racist statement: “Young Kin (now that’s an interesting take. Sounds Chinese, doesn’t it?) in Virginia couldn’t have won without me.”

And what was Youngkin’s response? “You all know me,” he told reporters, “I do not call people names. I really work hard to bring people together.” When a reporter noted that Trump was calling him a name, Youngkin said, “That’s not the way I roll and not the way I behave.”

None of this is to say that Youngkin is the best example of turning the page from Trumpism. Like many GOP Republicans he can seem torn, pulled between an angry Trumpist base and his own better judgment. He did, after all, campaign for Kari Lake, even though he is not an election denier and she most definitely is. I use him as an example because it’s still true that American politics would be undeniably better if politicians like him—as imperfect as they are—are the standard bearers for a post-Trump GOP.

Indeed, since politicians so often follow voters far more than they lead voters, it is ultimately up to us to demonstrate to them that the malice theory of American politics is truly a dead political end.

The worst thing for American politics would be for the Trumpist narrative—that decency is for the weak—to prevail. If cruelty truly is the sole or best path to partisan victory, then the continued temptation to yield to our worst impulses would grow overwhelming. The temptation was already strong enough to distort and transform the political culture of the right simply based on Trump’s single, narrow win.

As it is, however, the opposite message seems to be true. Ever since Trump beat Hillary Clinton, the Trumpist GOP lost and kept losing. A movement that prioritized vicious political combat lost the House in the 2018 midterms, lost the presidency and the Senate in 2020, and has likely blown a virtually unlosable election in 2022, despite the fact that the country is struggling under the great weight of the worst crime and inflation in at least a generation.

It turns out that there’s some life left in decency yet. Even when times are hard, there are voters who are unwilling to call good evil and evil good. It turns out that it’s hard to escape the need to persuade and inspire, and that might be the best—and most important—consequence of a midterm election that gave neither party a mandate but reminded the Republicans that malice and lies can do far more political harm than good.

One more thing …

This week’s Good Faith podcast reflected on the midterms and the “signs of the times.” What are the deeper lessons of the electoral outcome? There were five big-picture themes—three good and two bad. The good news was that malice lost, racial identity politics lost (more on that to come in a future newsletter!), and extremism lost. What was the bad news? We’re still very polarized, and the pro-life movement has lots of work left to do.

Give it a listen, and share your thoughts. What do you think the midterms say about the signs of our times?

One last thing …

I shared this song a few weeks ago, but I’m sharing it again because 1) I love it and believe messages like this are helping turn the tide against cruelty and hate, and 2) the new music video is lovely and features my neighborhood and many of my neighbors. Franklin, Tennessee, readers will recognize these folks and these streets. Enjoy:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.