Have you ever conducted a diversity training class? Or something like a diversity training class? I have, and it’s an illuminating experience.

As a brigade judge advocate in a reserve training brigade near the end of my legal career, it was my task to lead much of the training both during the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell” and during various sexual harassment/sexual assault “stand downs” (when we stopped normal training activities to address sexual misconduct in the ranks).

Because this was the Army, I had a script. We had to use specific PowerPoint decks and play specific videos. Some of the information was helpful, including detailing specific changes in command guidance and specific disciplinary processes. But when we got to the “values” sections, the same thing happened, every time. A small slice perked up and leaned in. The rest of the folks—the vast majority—tuned out and leaned back.

The same question was written all over their faces. “Please, can you just make it stop?”

It’s not that people don’t care about morality. And it’s not that people don’t respect gay soldiers or female soldiers or anyone else in the ranks. It’s just that PowerPoints and videos are not how you transmit or inculcate profound civilizational values.

All this is a preface to my key point. Today is my own personal Festivus, and I have a lot of problems with diversity training. While I’m not going to argue that all diversity training is poor quality, a lot of it is, and the net effect of all that poor training isn’t the indoctrination of a society, but the pointless division of our society, and a diversion from the measures that can bring real change.

As a practical matter, I think right and left make the same mistake about diversity training. They both believe it matters far more than it does. Advocates on the left hope it’s helping change society. Advocates on the right fear it’s changing society. In fact, it does virtually nothing to society at all, except divide us and distract us from the reforms and policies that truly matter.

In 2018, Harvard University professor Frank Dobbin and Tel Aviv University professor Alexandra Kalev published a fascinating summary of studies about the effectiveness of diversity training. It begins like this:

Starbucks’ decision to put 175,000 workers through diversity training on May 29, in the wake of the widely publicized arrest of two black men in a Philadelphia store, put diversity training back in the news. But corporations and universities have been doing diversity training for decades. Nearly all Fortune 500 companies do training, and two-thirds of colleges and universities have training for faculty according to our 2016 survey of 670 schools. Most also put freshmen through some sort of diversity session as part of orientation. Yet hundreds of studies dating back to the 1930s suggest that antibias training does not reduce bias, alter behavior or change the workplace. (Emphasis added.)

More:

We have been speaking to employers about this research for more than a decade, with the message that diversity training is likely the most expensive, and least effective, diversity program around. But they persist, worried about the optics of getting rid of training, concerned about litigation, unwilling to take more difficult but consequential steps or simply in the thrall of glossy training materials and their purveyors.

Dobbin and Kalev aren’t the only individuals to note that different kinds of diversity training are ineffective. Consider, for example, “implicit bias training” or the “implicit association test.” The idea is that you have “nonconscious prejudices and stereotypes” and those “nonconscious” prejudices” can impact real-world actions.

As a piece in Scientific American noted during the summer of unrest in 2020, implicit bias training is a “go-to” response for organizations under fire for racial bias or prejudice. There’s a problem however. While implicit bias may very well be real, implicit bias training doesn’t seem to affect behavior, and to the extent it has any impact at all, It seems to inflame employee anger:

While implicit bias trainings are multiplying, few rigorous evaluations of these programs exist. There are exceptions; some implicit bias interventions have been conducted empirically among health care professionals and college students. These interventions have been proven to lower scores on the Implicit Association Test (IAT), the most commonly used implicit measure of prejudice and stereotyping. But to date, none of these interventions has been shown to result in permanent, long-term reductions of implicit bias scores or, more importantly, sustained and meaningful changes in behavior (i.e., narrowing of racial/ethnic clinical treatment disparities). (Emphasis added.)

And the backlash is very real:

Even worse, there is consistent evidence that bias training done the “wrong way” (think lukewarm diversity training) can actually have the opposite impact, inducing anger and frustration among white employees. What this all means is that, despite the widespread calls for implicit bias training, it will likely be ineffective at best; at worst, it’s a poor use of limited resources that could cause more damage and exacerbate the very issues it is trying to solve.

Dobbin and Kalev also note that “antibias training activates stereotypes.” It’s not hard to see why. The internet is chock full of anti-bias and diversity training materials that explicitly rely on gross stereotypes.

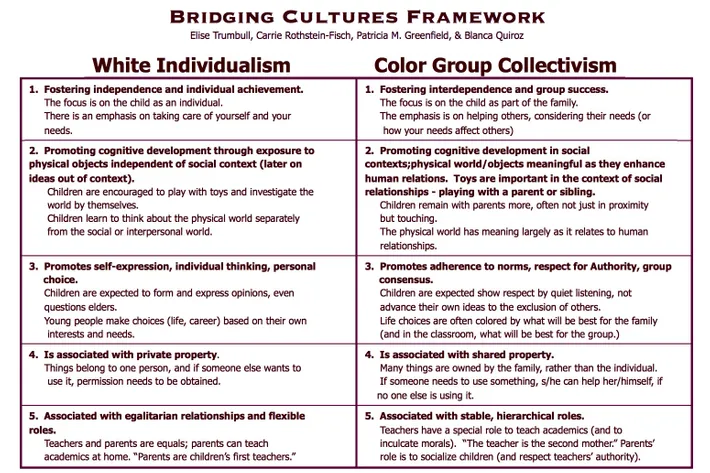

In an excellent piece in New York magazine, Eric Levitz asks progressives to object to “racist” diversity training materials and produces some rather choice examples. If this, for example, isn’t stereotyping, I don’t know what is:

Is this slide actually transforming hearts and minds in the real world? Sure, some people might be persuaded, just as other people counter that effect through negative backlash, but the vast majority do not walk away thinking, “I had no idea that private ownership of my car is a product of white individualism.”

So what’s the appeal of training like this? Or of more benign but equally ineffective diversity training measures implemented in other contexts? While there are of course some employers who are ideologically committed not just to the existence of diversity training but also to the specific content of that training, I think a better answer is summed up in two words—pain avoidance.

When a subset of employees cry, “Do something” then diversity training is “something.” When lawyers demand risk management, diversity training is an element of risk management.

But it all has a cost, and we see that cost play out every day. To the extent that most forms of diversity training have a real-world effect, it’s division. That small number of Americans who really care about the content of these slides are disproportionately concentrated in America’s leader class, and the effect of fights over diversity training is profound. The more radical elements are driving the national conversation.

The second consequence is distraction. I continue to be amazed and disappointed at the extent to which serious questions about the legacy and reality of American racism and the proper ways and means of dealing with persistent achievement gaps get diverted into arguments over rhetoric and PowerPoints.

And if you think the American people and American institutions have all the bandwidth they need to “do both”—to develop the best diversity training money can buy and to invest time, energy, and attention into the concrete policy changes and institutional initiatives that generate real opportunity and ameliorate historic injustice, then I’m afraid that’s just not reality. Think about how quickly attention in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder devolved from a serious debate about police reform into a series of conversations about cancel culture.

Here’s the good news. An increasing number of reasonable people on all sides of the political spectrum are waking up to what critics rightly call “DEI silliness.” (DEI is an acronym for “diversity, equity, and inclusion.”) And while much of the DEI silliness is just, well, silly, some of it can veer into a civil rights violation.

For example, when institutions create racial affinity groups or they engage in such comprehensive and unwelcome racial stereotyping that it becomes a form of racial harassment, they become a coercive instrument of the exact divisive forces they purport to despise.

The overreaction to diversity training excesses is to claim that its teachings are fundamentally transforming America. In reality, they have little to no measurable effect on Americans’ racial attitudes or their actions. But the underreaction matters as well, and we’re underreacting if we continue on the present course of pouring billions of dollars into an industry that divides and distracts more than it unifies and instructs.

The message to the corporate and educational establishment should be clear. Do diversity training (much) better, or don’t do it at all.

One more thing …

Keep your eyes on Jonah’s Remnant podcast feed. I did a Good Faith podcast preview with my new co-host Curtis Chang. We talked about Christians and the COVID vaccine, classical liberalism, and the meaning of the word “Evangelical.” It’s the first unofficial episode of our brand new podcast, and I look forward to your comments and critiques.

Also, I had such a great response to the ask me anything live video, that I plan to do it again, soon. Details to come!

One last thing …

Down by two. Less than a minute to go. You’ve got the ball. What do you do? You dunk in traffic, that’s what you do.

Then, when you get the ball back, the game is tied, and the clock is winding down, what do you do? You drain a ridiculously deep 3-pointer. That’s what you do.

Ladies and gentlemen, Ja Morant:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.