Three things are true at once. First, the United States is the most Christian advanced democracy in the world. Even with declining rates of religious belief and declining rates of church attendance, a solid supermajority (65 percent) of Americans identify as Christian.

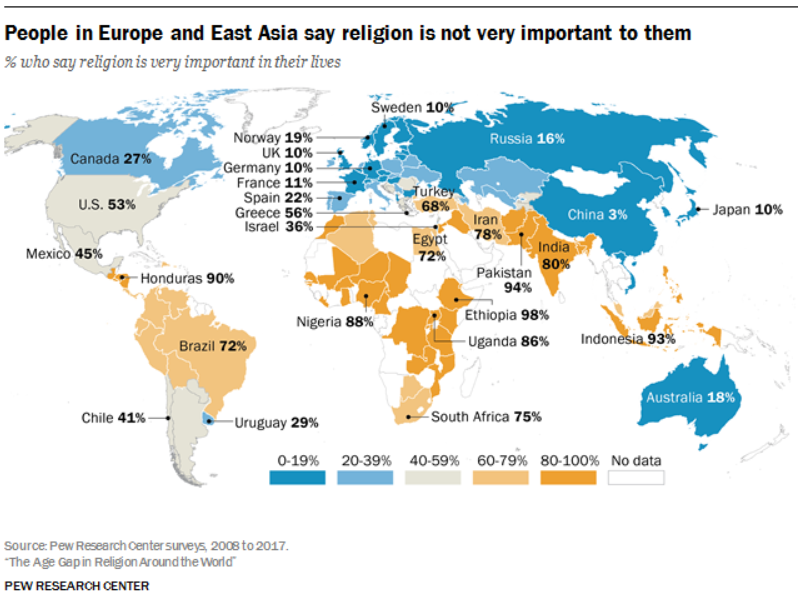

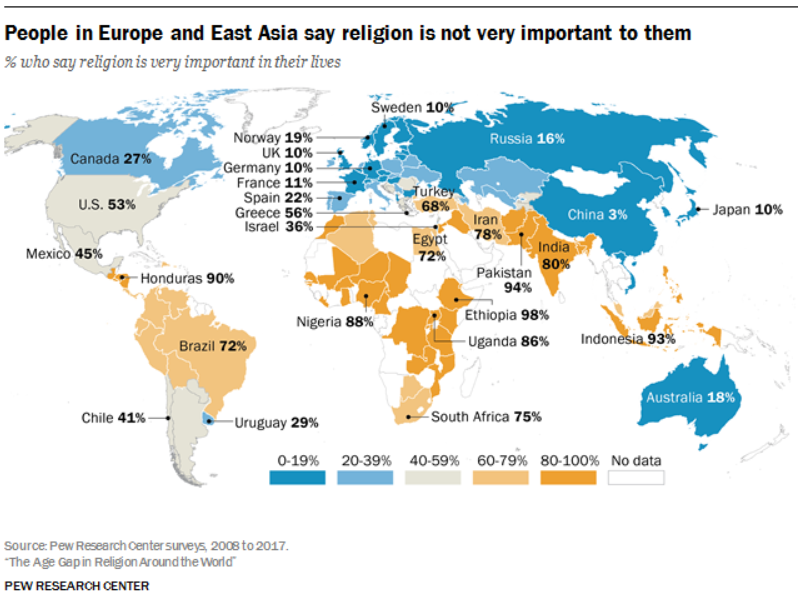

America’s exceptional religiosity isn’t just measured by adherence but also by intensity. Look at the Pew Research Center chart below, which measures the percentage of people by country who say that religion is “very important in their lives.” While there are developing countries that are close to (or exceed) the United States, there is not one other true peer nation that is both mostly Christian and where most people say their faith is “very important”:

Second, both the Republican and Democratic parties are utterly dependent upon their most devout members for their electoral success. As I’ve noted before, nonwhite Democrats (and especially black Democrats) are among the most God-fearing, churchgoing members of American society. At the same time, the Republican Party would be irrelevant without its own white Evangelical base.

The bottom line is that Christians in both parties have absolute veto power over (at the very least) the party’s national candidates. In many states that veto power extends to statewide candidates, congressional candidates, and even candidates for the smallest local positions.

Third, American political culture is a toxic, hyperpartisan, corrupt, and increasingly violent mess. Given the first two factors mentioned above, this should not be. After all, Jesus could not have been more clear. In John 13, he declared, “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.” That’s the dream. Here’s the reality:

Again, remember that both of these coalitions are chock-full of Christians. It is not the case (at least not yet) that America has one religious party and one secular party. The mutual loathing you see comes from people who could recite every syllable of the Apostles’ Creed side-by-side and believe wholeheartedly in the divine inspiration of scripture.

How does this happen? The longer I live the more convinced I am that our Christian political ethic is upside down. On a bipartisan basis, the church has formed its members to be adamant about policies that are difficult and contingent and flexible about virtues that are clear and mandatory.

To understand what I mean, let’s refer back to one of my favorite passages in scripture—Micah 6:8. Like many biblical passages, it is simple to understand yet tough to execute: “He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God.”

In many ways, each of those virtues is in tension with each other. Humility requires us to acknowledge our own limitations and inability to formulate political responses to complex human problems. For example, how do you close the racial achievement gap in American education? What are the just limits of individual liberty? How do you decrease violent crime? Is there a path to public safety that does not include mass incarceration?

Yet while we can and should recognize the possibility that we can be wrong, we can’t be paralyzed into inaction. We might be wrong, but we have to try to do what’s right, as best as we can discern it.

But then the instant we press on to “do justice” the demand to “love kindness” appears to block the way. How many times have we heard the claim that the “old rules” of civility and decency are simply inadequate for the times? That’s a core argument of the new right, for example. We tried decency, they say, and it didn’t work. Now is the time to punch back.

Yet that mindset is utterly antithetical to the Christian moral ethic. You’re not kind until kindness doesn’t work. You’re to be kind even through the most brutal acts of repression and in the face of complete political defeat.

In the face of the moral complexity and difficulty of the true Christian moral call, we’ve created a hierarchy of values. It’s not that we absolutely reject kindness or humility or decency. It’s not that we’re going to condemn the fruit of the spirit—love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control—it’s just that they’re “secondary values.” When push comes to shove, it’s our vision of justice that matters.

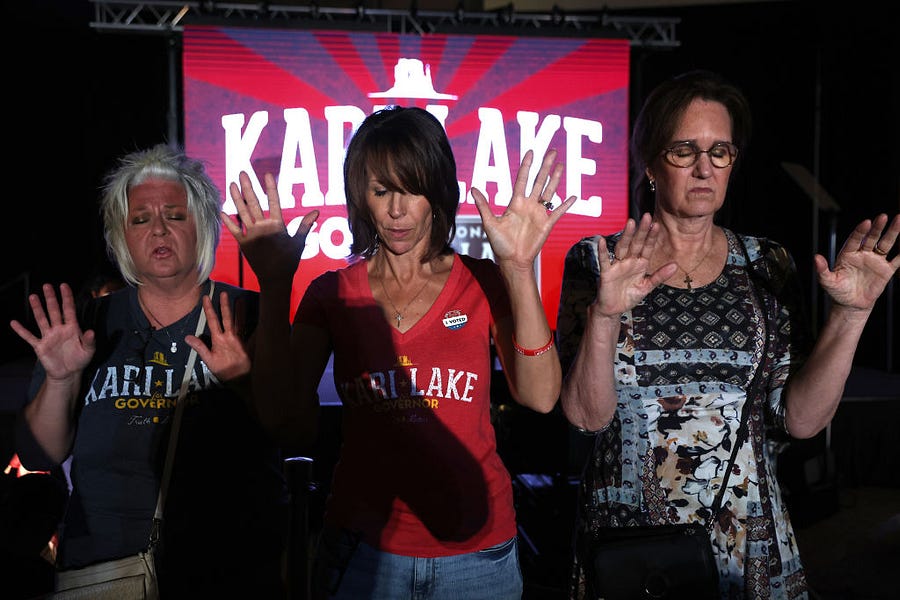

This is why, for example, a Republican like Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake (who leads her campaign bio with the words “faith courage truth”) can absolutely count on Republican Evangelicals to turn out for her en masse even though she has spread an avalanche of election lies and in spite of her proud crudeness in publicly praising Ron DeSantis’ and Donald Trump’s so-called “BDE” (which stands for “big dick energy”):

The same analysis applies to Pennsylvania’s Doug Mastriano and a host of other MAGA Republicans—Christian politicians who act as if entire sections of clear biblical moral commands simply don’t exist so long as they take the “just” (in right-wing eyes) position on issues of social and cultural consequence.

But here’s the paradox—forsake one virtue for another, and you increase the chances that gain nothing at all. To put it another way, when we transgress moral laws, we’re fools if we think we can control the consequences.

It turns out that since justice is often hard to achieve, we often need humility to understand all the complexities, and kindness maintains the relationships that are indispensable to an exchange of ideas. Block out half of America, for example, and you’re going to lose access to the relationships and knowledge that enrich your understanding even of the issues that you care about the most.

When I encounter the most partisan preachers and public Christian personalities, I’m often gobsmacked at the inverse relationship between their political certainty and their political knowledge. The less they know about an issue, the more confident they’re obviously right.

(This is a confession, by the way. To take one example—the more I began to understand about the reality and legacy of racism in America, the less certain I became in my conventional, confident conservatism about law, liberty, and economic opportunity. I’m now far more open to contrary views.)

Earlier this month I was in a conversation with friends, and one of them brought up how he’s combatting the pull toward animosity by revisiting the civil rights movement. In face of indescribably greater oppression than any American community faces today (including the American Evangelical community) its leaders and members demonstrated a degree of grace and forbearance that feels unimaginable today.

In a 2004 interview, the late John Lewis described the approach:

In preparing for the sit-ins, we felt that the message was one of love — the message of love in action: don’t hate. If someone hits you, don’t strike back. Just turn the other side. Be prepared to forgive. That’s not anything any Constitution say anything about forgiveness. It is straight from the Scripture: reconciliation.

No one can argue that the civil rights movement neglected the quest for justice. At the same time, no one can credibly argue that it sacrificed the fruit of the spirit in that urgent quest. It demonstrated that fruit, even in the face of beatings, lynchings, fire hoses, and dogs.

And the argument now is, what? That these acts of love and grace were all well and good when dealing with Jim Crow, but now we’ve got wokeness to confront?

In recent years I’ve taken to rereading scripture through a specific lens—understanding that all of scripture was written to a community of believers that enjoys a fraction of the wealth and power we take for granted today, and that the entire New Testament was written to a church that had no meaningful political voice and endured violent religious persecution.

And here’s what we find—the description of biblical justice is less specific than the multiple descriptions of biblical virtue. That doesn’t mean we have no standard for justice at all. As Tim Keller has argued, biblical justice is characterized by radical generosity, universal equality, “life-changing advocacy for the poor,” and corporate and individual responsibility.

That conception of justice gives us a frame for discussing policy. It does not provide the specific answers. Biblical virtues, by contrast, are far more precise and far more detailed. This makes sense, especially for scripture that is intended to guide us in all nations, in all times. The “what” of politics (the specific policies we support) will evolve. They’ll often be debatable. We’ll have uncertain answers to complex questions.

But the “how” of politics—the virtues we display as we engage—don’t evolve at all. The fruit of the spirit is timeless. There is no political emergency that justifies a departure from these core values. Scripture anticipates that Christians will face evil, yet the command is clear: “See to it that no one repays evil for evil to anyone, but always pursue what is good for one another and for all.”

Christian young people are often taught that they should be countercultural. The youth group version of that admonition goes something like this: When the world is profane, your speech is clean. When the world is drunk, you are sober. When the world is promiscuous, you are chaste. How do you know we’re Christian? We don’t cuss, drink, or have premarital sex.

But the call to counterculture is much more comprehensive. When the world is greedy, you are generous. When the world is cruel, you are kind. When the world is fearful, you are faithful. When the world is proud, you are humble. How do you know we’re Christian, by our love.

Yes, we say. Yes to all of this. Right until the moment when we think that our kindness, our faithfulness, or our humility carries with it a concrete political cost. We think we know what’s just, and we can’t do justice without power.

And so, in our arrogance, we think we know better than God. We can’t let kindness or humility stand in the way of justice. Yet we’re sowing the wind, and now we reap the whirlwind. The world’s most-Christian advanced nation is tearing itself apart, and its millions of believers bear much of the blame.

One more thing …

It’s not often that I’m going to recommend a Twitter thread, but this series of tweets by Rabbi Dr. Ari Lamm is absolutely fascinating. It’s about how the nuances of the Hebrew language help us better understand the Tower of Babel. Take a couple minutes. Read it all:

One last thing …

There is nothing quite like mass corporate worship. At its best it’s a reminder that the church is a “great multitude” from “every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages.” This song is simple and beautiful, sung before a great multitude. Enjoy. I hope it blesses you as much as it blessed me:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.