Today is the first day of the impeachment trial, and I expect that we’ll spend far too little time talking about the actual central question of the case. Also, let’s talk a bit about “moderate” Pete Buttigieg’s legal extremism. Today’s French Press:

-

We know the material facts about impeachment; now let’s discuss their meaning.

-

Pete Buttigieg fails the First Amendment test.

Was Donald Trump’s misconduct severe enough to merit removal?

If I had to sum up the case against Donald Trump in one sentence, it would be this: The available evidence demonstrates that the president of the United States attempted to coerce an allied nation to investigate a self-serving, debunked conspiracy theory and a prominent domestic political rival as a precondition to receiving vital American military aid. If I have another sentence to expand on the claim, I’d add that he attempted to accomplish this scheme by using his private attorney to supplement and circumvent normal diplomatic channels for the purely personal benefit of the president.

The evidence in support of the contentions above is overwhelming, including—most importantly—the words of the president himself recorded in the memorandum of the conversation between him and President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine. Zelensky raised the possibility of purchasing much-needed Javelin missiles to bolster Ukrainian defenses in its shooting war with Russian, of our primary geopolitical foes. Trump responded with two explicit investigation requests—an investigation seeking a (mythical) Crowdstrike server in Ukraine and an investigation of Joe and Hunter Biden.

Moreover, the impeachment inquiry uncovered evidence of extensive formal and informal diplomatic efforts dictated by the president’s personal needs. The U.S. ambassador to the Ukraine was targeted for smearing and removal based on her perceived opposition to this personal quest, and American diplomats attempted to pressure Ukrainians to announce the existence of investigations. And while the president’s team may claim there is insufficient evidence to prove those conclusions, say, beyond a reasonable doubt (though there is certainly a preponderance of evidence in support), they have also blocked access to additional testimony and evidence that could establish (or refute) additional personal presidential involvement in the scheme.

Many of the best and most thoughtful of the president’s defenders (including my friends Erick Erickson and Andrew McCarthy) have made the defense the president himself won’t make—that his conduct was bad, but it was not impeachable. This close to an election, let the people decide.

It’s a serious position held by serious people. It’s the position I held myself in response to the Mueller investigation and in the aftermath of the Stormy Daniels scandal. Expose the president’s wrongdoing, and let it be part of the electoral calculus. It’s a powerful argument. But let me explain an aspect of the case that I believe renders the president’s misconduct especially egregious, calls into question the effectiveness of the normal checks and balances against the executive branch, and tips the scales towards a vote to convict.

First, let’s make one thing abundantly clear—Donald Trump is not the first modern American president to abuse the power of his office. Presidents have violated the Constitution, stretched their power past statutory limits, and otherwise behaved in ways that would shock the founders. But in the vast majority of those instances, there was immediately available constitutional check on the president’s conduct—a check that could rein in the executive branch without the disruption of removing the president from office.

Let’s take, for example, President Obama’s famous use of “pen and phone” to unilaterally change federal law without either congressional action or regulatory rulemaking. States and individuals had immediate access to courts to reverse the administration’s actions, and when the courts ruled against the administration, the administration complied with the rulings. Even when the administration targeted Tea Party groups for harassment, court remedies were also immediately available. We could (and did) file suit against responsible officials and could (and did) receive legal relief. I remember it well. I was part of the legal team that represented dozens of aggrieved Tea Party chapters.

The give-and-take of presidential overreach, legal challenge, and legal defeat has become part of the sad, new normal of American politics. Democrats and Republicans alike elect presidents who strain at the constitutional leash. They abuse their power. And sometimes they even seem motivated by partisan political malice.

But President Trump’s conduct regarding Ukraine was different. Here was a president, operating at the absolute apex of his constitutional powers, steering international diplomacy for personal benefit, and not only were there no clear means of constitutional restraint, there was obvious intent to accomplish the scheme well outside the public eye. The scheme was blocked by the unlikely combination of whistleblowing and informal political pressure. Even worse, a defiant administration refuses to admit to any wrongdoing at all—even calling the key piece of evidence against the president a “perfect” call. It was essentially our good fortune (through the courage of the whistleblower) that the American people have access to partial information about the scandal so they can factor it into their electoral calculus.

What’s the constitutional check for misconduct of that kind? Citizens can’t run to court to block this particular abuse of presidential power. We can’t even count on public knowledge for public accountability. The administration is still actively holding back material evidence.

The checks and balances of the American constitutional republic are far-reaching, and the framers—in their wisdom—established an ultimate check on the president. When no other structure of government can restrain his abuse of power, Congress can impeach him and remove him from office. When presidents promulgate unlawful rules and regulations, we can take them to court. When presidents announce unpopular policies, we can vote for their opponents. When presidents work in secret to substitute their personal priorities for the public good in a strategically vital region of the world, the conventional checks are unreliable. In that context, impeachment is the difference between punishment and permission when a president abuses his power while conducting affairs of state.

Pete Buttigieg is radically opposed to religious liberty.

Is it possible that the most religious candidate in the Democratic primary is also the most hostile to religious liberty? If you’ve followed Pete Buttigieg at all, you know that he’s outspoken about his Christian faith. He brings Christian arguments into the public square, justifies his policy positions in part by reference to his Christian values, and has given every indication that he wants to fight hard against the idea that the Democrats are a secular party.

On one level, this is welcome. Although I disagree with many of Buttigieg’s policy positions (and have strong theological disagreements with many aspects of his Episcopal faith), I’ve always rejected the idea that Christians should abandon faith-based arguments in political debate.

Arguing from faith principles is honest (it’s what you really believe) and it’s quite often persuasive. Tens of millions of Americans make decisions based on religious values and principles. So let’s have the debate. When scripture asks us to care for the poor, what does that mean? What does it mean for a nation? What does it mean for individuals?

But for a man who so obviously values his church and his faith, Mayor Pete is extraordinarily dismissive of religious freedom. Writing in the Washington Post, Michael Gerson charitably called Buttigieg’s position “minimalistic.” I’d call it radical. Here’s the relevant excerpt:

On policy issues of particular concern to many evangelical Christians, Buttigieg gives little ground. His conception of religious liberty is minimalistic, making no provision for religious institutions such as colleges to admit or hire according to their traditional religious standards. “If you are talking about professional organizations that have HR departments,” he told me, “then yes, it is not enough to say religion inspires me to discriminate against you and expect government to let that go.”

Let’s briefly unpack this comment. First, the existence of an HR department or the professional character of an organization is constitutionally irrelevant to its First Amendment rights. There are churches that employ well over hundreds of employees, including pastoral employees. Christian ministries can employ thousands. Each of these organizations is centered a specific set of values and religious ideals. It’s basic, black-letter constitutional law that the First Amendment protects their religious freedom, free speech, and freedom of association.

I’d ask Mayor Pete if he disagrees with a case called Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. EEOC. In Hosanna-Tabor, the Supreme Court ruled against an Obama administration effort to apply nondiscrimination law to the school’s employment decisions regarding its ministerial employees. The court held that both the Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause tell the government to “let that go” even if the school is deemed to discriminate.

Was that case 5-4, with the four Democratic appointees adopting the Mayor Pete position? Nope. It was 9-0. Mayor Pete is to the left of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor.

Moreover, what—precisely—is the state’s interest in interfering with the hiring and firing decisions of Christian organizations? Nobody is forced to work at a Christian institution. They represent only a small fraction of the American economy. Allowing Christian organizations to maintain their distinctive religious character does not materially impair the opportunities or individual liberties of any American citizen. If you don’t like the rules of a Christian school, don’t go. If you don’t want to comply with Christian sexual ethics, don’t apply to work at a Christian ministry that upholds traditional Christian teachings.

It is exactly right to question Christians if they defend conduct in President Trump that they’d condemn (and have condemned) in other presidents. It’s exactly right to question whether Evangelicals should abandon character tests for president—after loudly proclaiming the importance of character for so many years. It’s very much worth worrying about the impact on the Christian witness when prominent Christians exhibit so much rage and fear and so prominently and blatantly change their position depending on the prevailing partisan winds. At the same time, however, exactly no one should be surprised at widespread Evangelical opposition to Democrats when even a “moderate” takes a radical stand against the First Amendment.

One last thing …

In the aftermath of the Titans loss in the AFC Championship, I’ve been flooded with good-natured condolences and well-wishes. But I’m not too upset. After a 2-4 start, the playoffs seemed like a pipe dream. To then make the playoffs and beat the Patriots and Ravens on the road? That was beyond our wildest dreams. To pay tribute to a great playoff ride, I’m giving the people what they want, and the people want a YouTube of Derrick Henry’s season highlights. Enjoy:

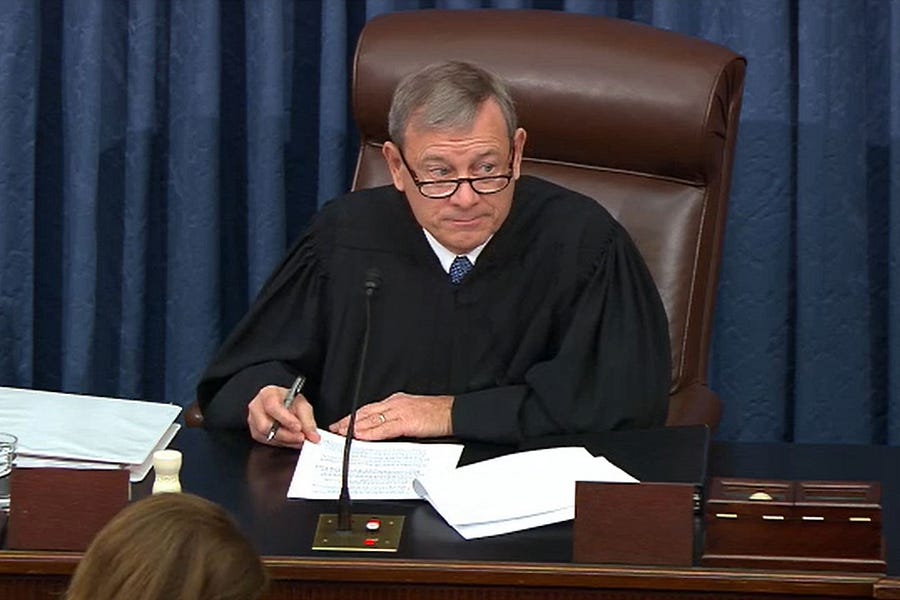

Screengrab of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts presiding over impeachment proceedings against U.S. President Donald Trump in the Senate at the U.S. Capitol on January 21, 2020 in Washington, DC, from Senate Television via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.