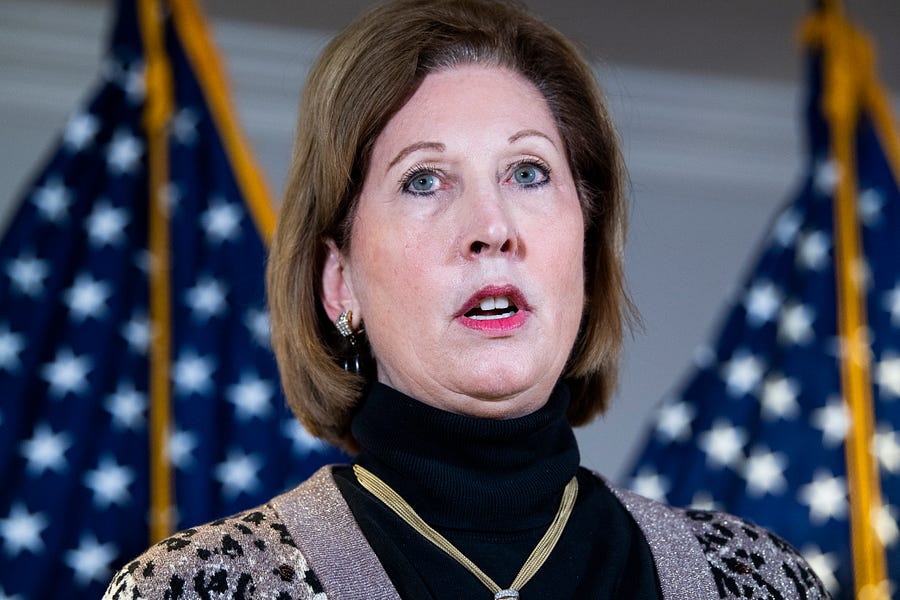

Ok, let me begin with an apology. I’ve violated the First Commandment of The Dispatch—“Thou shalt not write clickbait headlines.” But in my defense, I got my inspiration not from a clickbait website but rather from—of all places—PBS. Its writeup of a Georgia federal district court’s decision to dismiss Sidney Powell’s “kraken” lawsuit is entitled, “Judge Finds ‘Kraken’ Election Challenge Lacking, Dismisses Lawsuit.” My headline is just a bit more down-home and direct.

Now, on to the main event. We’re in the midst of a strange and disturbing phenomenon. At the same time that the Trump campaign and his allies are experiencing a wave of defeats in court—including at the hands of Republican appointees (including Trump appointees and judges on Trump’s shortlist for SCOTUS)—many Trump supporters are increasingly convinced that the election was stolen.

And what is helping convince them? The exact claims that are being tossed out of court on a daily (and sometimes hourly) basis. So I thought it would be worth taking a bit of time to explain why these cases are being tossed and why some folks still find them so very convincing, even when they lose.

First, let’s break this down as simply as possible. To prevail in a case, at a minimum you have to present 1) a valid legal claim; 2) filed on a timely basis; 3) supported by admissible evidence; that 4) seeks lawful relief.

Time and again, the Trump and Trump-allied cases clearly and obviously fail to meet multiple prongs of this test. Take the so-called “Kraken” cases. These are the cases filed by Sidney Powell in multiple states that allege extreme levels of fraud and vote manipulation and seek to overturn the elections in each state.

On Monday, federal judges tossed Kraken lawsuits out of court in both Georgia and Michigan. In Georgia, the judge (a George W. Bush appointee) delivered his ruling from the bench. Per Politico:

“They want this court to substitute its judgment for two-and-a-half million voters who voted for Joe Biden,” Batten said, calling it perhaps the most extraordinary relief ever sought in an election lawsuit. “And this I am unwilling to do.”

Batten rejected the suit on multiple grounds, including the timing of the complaint, the standing of the plaintiffs and the extreme relief they were seeking.

In Michigan, the judge issued a written ruling that dismantled Powell’s legal and factual arguments (describing many of the factual claims as mere “speculation”) and concluded:

This lawsuit seems to be less about achieving the relief Plaintiffs seek—as much of that relief is beyond the power of this Court— and more about the impact of their allegations on People’s faith in the democratic process and their trust in our government. Plaintiffs ask this Court to ignore the orderly statutory scheme established to challenge elections and to ignore the will of millions of voters. This, the Court cannot, and will not, do.

To get a sense of the “evidence” Powell presented, part of her case hinged on a redacted affidavit from a person identified only as “Spyder” who describes himself or herself as a “white hat hacker.” The affidavit itself reads like Star Trek-style technobabble (Scotty! Use the dilithium crystals to reboot the voting machines!), but the part that’s decipherable is patently absurd to the point of hilarity. For example, follow this short tweet thread by Julian Sanchez (language warning):

To recap, Powell didn’t file on a timely basis, couldn’t support her claims with admissible evidence, and sought relief that the courts could not grant.

Let’s move on to another lawsuit: the extraordinary case filed by the attorney general of Texas in the Supreme Court to challenge the election results in Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin. There’s one thing that is credible about the case—that it was filed directly at SCOTUS. The Constitution grants the court original jurisdiction to hear cases between states.

But beyond filing the case in the proper venue, the complaint is woefully deficient. Incredibly, it purports to claim that the election outcome was virtually statistically impossible, featuring a nonsense allegation:

The probability of former Vice President Biden winning the popular vote in the four Defendant States—Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—independently given President Trump’s early lead in those States as of 3 a.m. on November 4, 2020, is less than one in a quadrillion, or 1 in 1,000,000,000,000,000.

Wait. What?

The reason Trump ultimately lost when he was leading earlier in the evening is simple—large, heavily-Democratic counties were slower to count their votes, and they didn’t report their totals until later. Moreover, one reason some jurisdictions didn’t report until later is that Republican legislatures prohibited them from counting hundreds of thousands of mail-in ballots before election day. The delay was a product of political choices, not corruption.

That’s not hard to understand, but if you want to read more Star Trek-style technobabble (really, statistics babble), get a load of this excerpt of the court filing in support of the claim of improbability:

If you want to dive into all the flaws in the analysis, follow this thread. It’s not necessary, but it is amusing (again, language warning):

The statistical allegation isn’t the entirety of the Texas case, of course, but its mere presence is shocking. The rest of the case suffers from different deficiencies. Texas is challenging the way other state officials have interpreted and applied the election laws of those states. Yet Texas doesn’t have standing to raise those claims. That’s a matter of state law to be settled by litigation between proper parties in the state court of the relevant state.

In fact, the vast majority of state election disputes don’t even implicate federal law at all. There’s even a legal doctrine (called the Purcell principle after the 2006 case Purcell v. Gonzalez) that admonishes federal judges to restrain themselves from making changes in election law close to an election. Given Purcell, it’s preposterous to think that SCOTUS would both alter election law after the election and toss out the results of the vote.

I’ll make this short. There is no chance the Supreme Court will grant the relief Texas seeks.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that even substantive and serious legal challenges can and must be thrown out of court when they’re filed at the wrong time and seek the wrong relief. As I typed this newsletter, the Supreme Court rejected (with no dissents) Congressman Mike Kelly’s attempt to overturn the election results in Pennsylvania.

Kelly’s lawsuit raises an interesting question of Pennsylvania law: Were the commonwealth’s 2019 election reforms that expanded mail-in voting consistent with the Pennsylvania constitution? But note the date of the reforms. Kelly could have raised his challenge well before the election. He should have raised his challenge before the election. So it was no surprise that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court rejected his lawsuit as filed too late.

It was even less surprising that SCOTUS refused to engage. Why? Because the Pennsylvania Supreme Court is the final authority on the meaning and interpretation of Pennsylvania law and the Pennsylvania constitution, not SCOTUS.

Everything I’m telling you in this newsletter is elementary. It represents basic election law, basic constitutional law, and basic rules of evidence. So why does the GOP belief that the election was stolen persist even through repeated, decisive legal defeats?

There’s a complicated answer and a simple answer. Let’s ignore the complicated answer for the moment—it’s based in the enduring human vulnerability to conspiracies compounded by widespread and increasing distrust in institutions. In short, to greater and lesser degrees conspiracy theories will always be among us.

In this case, however, the challenge of human nature is compounded by the fact that multiple trusted conservative and Republican voices are making arguments they know—or should know—aren’t just wrong, but frivolous.

In normal circumstances, a legal personality like Mark Levin would shred the arguments in the Pennsylvania case. Instead, he promoted it. Ted Cruz has the legal skills to know the case has no hope. He offered to argue it at the Supreme Court. And I know the attorney general of Texas well enough to know that this lawsuit is far beneath his level of legal expertise.

In other words, lawyers who should know better are conning their own fans and constituents. Credentialed charlatans are telling frightened and sad Americans exactly what they want to hear about topics they have no reason to understand. Is it any wonder they believe?

Coming attractions …

Meanwhile, even as Trump is trying desperately to cling to power, Joe Biden is preparing to govern. He’s made a battery of nominations to his cabinet, and one is particularly objectionable—Xavier Becerra as secretary of Health and Human Services.

In the spirit of Festivus, I plan on airing my grievances against the pick. If a GOP senate survives the Georgia runoff, it should seriously consider rejecting Becerra. I’ll explain why on Thursday.

One last thing …

Speaking of Festivus, here’s a primer for young readers—those who missed the glory of Seinfeld. Enjoy and remember the comedic greatness of Jerry Stiller:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.