In all the discussion of Glenn Youngkin’s victory over Terry McAuliffe, there’s a word that’s largely missing from the analysis: abortion. And, on first glance, that’s quite a surprise. This was supposed to be one of the most concretely consequential elections for abortion rights in a generation. Yet in the end, the issue hardly mattered at all.

The reasons why should teach hard lessons to both sides of the argument. Ultimately, however, they signal a reality that’s deeply encouraging to those who seek to end abortion in the United States. The issue is waning in importance in part because abortion is waning in prevalence, and even pro-choice Americans don’t view abortion as a “desirable good.”

Let’s start with a brief explanation as to why the Virginia election was so politically consequential. If you look at the legal developments in the fight over abortion rights, the issue hasn’t been this contested and this salient since 1992, when the Supreme Court reaffirmed the right to abortion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

The day before the Virginia election, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in two challenges to SB 8, the Texas law that bans abortions after a heartbeat is detected and then empowers virtually any person in the United States (aside from Texas state employees) to sue any person who performs an abortion or “aids or abets” the performance of an abortion.

SCOTUS heard these cases less than a month before it will hear arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case that challenges Mississippi’s ban on abortion after 15 weeks. The state of Mississippi is explicitly asking the court to overrule Planned Parenthood v. Casey and Roe v. Wade and essentially extinguish the constitutional right to abortion.

If the court does overrule Roe and Casey, then for the first time since 1973, states would be empowered to ban abortions within their borders. Even if the court doesn’t overrule Roe and Casey, if it doesn’t also block SB 8 then states will possess a legal roadmap for restricting abortion rights well beyond post-Roe norms.

To put the matter plainly, it’s entirely possible that the Supreme Court will meaningfully (and perhaps even dramatically) increase state authority over abortion rights. This means the candidates’ respective opinions on abortion potentially mattered more than any candidate’s position in almost 50 years.

McAuliffe understood this reality and made the threat to abortion rights one of the centerpieces of his campaign. In late October, CNBC reported that three of McAuliffe’s most expensive ads targeted Youngkin for his pro-life stance. They were “among the former governor’s most aired ads on broadcast or cable television, with each airing over 1,100 times.”

McAuliffe made a campaign stop in September at an abortion clinic, and—as my former National Review colleague John McCormack pointed out—pieces in the New York Times, NPR, and the Washington Post accurately noted that the race would prove an interesting test of “the new politics of abortion.”

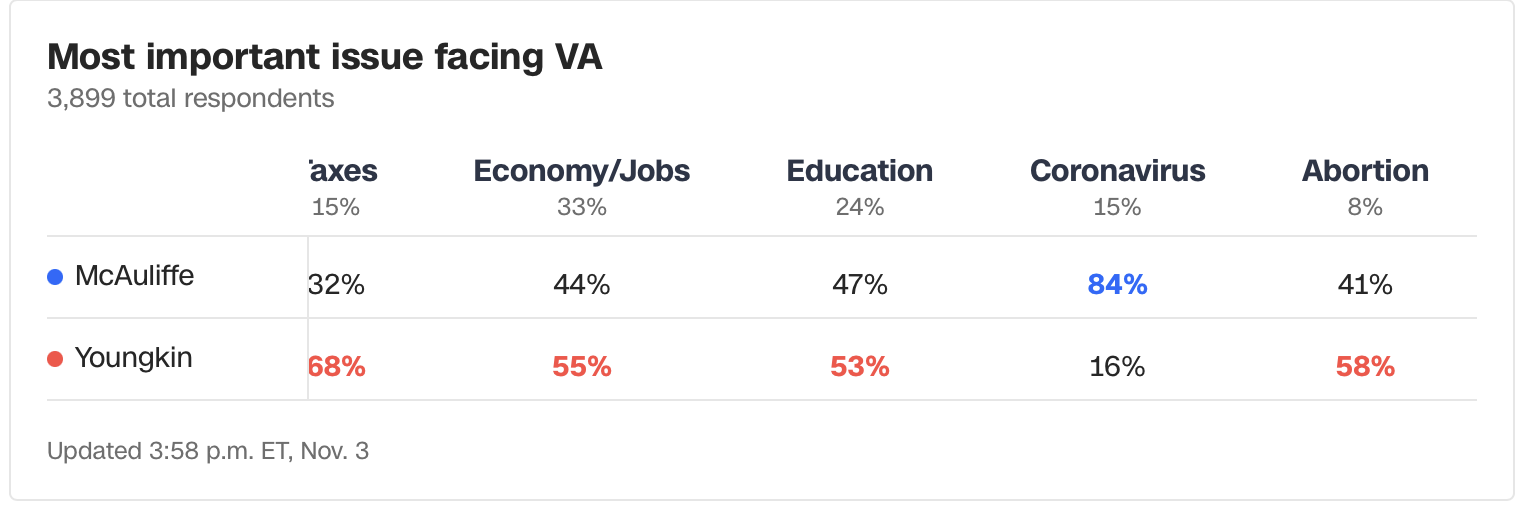

And what happened? If the exit polls are to be believed, the issue fizzled. Voters largely did not care. Only eight percent listed abortion as their top issue, and of those eight percent, 58 percent voted for Youngkin. The economy, education, taxes, and coronavirus were all far more consequential:

If you spend your life online (and you shouldn’t!), you might be shocked. Few issues generate more Twitter intensity than abortion. Offline? The reality is quite different. We know that opposition to abortion rights motivates white Evangelicals far less than their leaders’ rhetoric would suggest. Eastern Illinois University’s Ryan Burge, one of the nation’s leading statisticians of American religion, has noted, for example, that immigration drove Evangelical support for Trump more than abortion.

The Virginia race itself illustrates the surprising unimportance of abortion to self-described white Evangelicals. A full 27 percent of the Virginia electorate identified as white born-again or Evangelical, and that clearly means a large majority did not rank abortion first, even though this could be the most consequential election for state abortion rights in a generation.

But if pro-life Evangelicals weren’t prioritizing abortion, then pro-choice voters were prioritizing it even less. Voters focused on protecting abortion rights were the minority of a small minority. They were 41 percent of the eight percent. McAuliffe’s giant ad buys represented a tremendous swing and miss. He made the argument. Pro-choice Virginians simply didn’t respond.

Why the indifference? In a smart post, McCormack rightly argues “what happens in one state won’t have much of an impact on how voters vote in other states.” In other words, Texas isn’t Virginia, and Virginia voters rightly care less about Texas. Also, Youngkin didn’t stake out an abolitionist position on abortion during the race. He identifies as pro-life and supports additional abortion restrictions under Virginia law, but he has stopped short of pledging an abortion ban.

At the same time, however, I do wonder if something much deeper is going on—something that isn’t directly related to politics, but rather to the two powerful cultural realities in the United States that I’ve identified time and again. Abortion rates and ratios have declined dramatically, and even abortion supporters tend not to believe abortion is a “desirable good.”

With apologies to longtime readers, it’s worth reviewing the facts. In my experience, few Americans understand how dramatically abortion rates have declined since their highs in the early 1980s. According to data from the pro-choice Guttmacher Institute, the abortion rate (abortions per 1,000 women) is below the rate when Roe was decided, and when Roe was decided abortion was illegal or sharply restricted in most states.

If you think the abortion rate decline is entirely the product of a decreasing American birth rates, think again. Not only has the abortion rate declined, so has the ratio (abortions per 1,000 pregnancies), and so has the absolute number of abortions performed per year.

In 2017 (there tends to be rather substantial lag time in abortion rate reporting), there were 13.5 abortions per 1,000 women. That’s well less than half the peak, and it represents the continuation of declines that have occurred in every American presidency since Carter’s, regardless of whether the president was pro-life or pro-choice.

The reasons for the decline are varied and complex—and contraception plays a big role in the story—but it’s also true that even abortion rights supporters have mixed feelings about the practice itself. The best single study I’ve ever read about American attitudes towards abortion comes from Tricia Bruce at Notre Dame.

Abortion can be notoriously hard to poll, with answers highly dependent on question phrasing and citizen knowledge. How many respondents truly understand that overruling Roe won’t ban abortion nationally, but rather leave the issue for states—or potentially Congress—to resolve?

Bruce took a different approach. She and her team conducted 217 in-depth interviews of a demographically-representative cross-section of Americans. The interviews lasted an average of 75 minutes, and the questions were designed to “elicit thoughts, feelings, and experiences connected to abortion attitudes.”

The responses were fascinating, and I’ve written about them repeatedly. They provide an in-depth understanding of the nuances of American thoughts, and it should be required reading for advocates on both sides of the pro-life/pro-choice divide. But of all the findings, this stands out:

None of the Americans we interviewed talked about abortion as a desirable good. Views range in terms of abortion’s preferred availability, justification, or need, but Americans do not uphold abortion as a happy event, or something they want more of. From restrictive to ambivalent to permissive, we instead heard about the desire to prevent, reduce, and eliminate potentially difficult or unexpected circumstances that predicate abortion decisions (whether of relationships, failed contraception, lack of education, financial hardship, or the like). Even those most supportive of abortion’s legality nonetheless talk about it as “hard,” “serious,” not “happy,” or benign at best. (Emphasis added.)

In fact, the first sentence is entirely consistent with what I hear from thoughtful pro-choice advocates all the time. They seek to preserve abortion rights not because people are “happy” to have abortions, but rather because they feel an abortion is a sad necessity, or prudent but hard.

But let’s combine the abortion data with attitudes about abortion itself. The reality is that fewer and fewer American women are availing themselves of a procedure that virtually none of them affirmatively like. That is not generally a recipe for real-world political intensity. It means abortion is increasingly out of sight (alien to personal experience) and out of mind (unpleasant to think about).

Consider a counter-factual. Would fights over free speech, religious freedom, or gun rights be more or less intense if, in any given year, (a) few people exercised those rights, and (b) those who exercised their rights considered that exercise “hard” or “serious” and definitely not a “desirable good”?

Most people who prioritize the defense of free speech, religious freedom, or the Second Amendment both value the right and often relish its exercise. They find meaning and purpose in vocalizing their ideas, living their faith, or protecting their families.

It’s impossible to know if the (relative) public indifference to the abortion debate will impact the Supreme Court. Even if it does impact the Court, it’s anybody’s guess as to the direction of that impact. My friend John McCormack argues that the Virginia results provide evidence “that if the Supreme Court does restore the right of the American people to enact laws protecting the lives of unborn babies, there would not be some sort of overwhelming nationwide backlash against Republicans at the polls in 2022.”

He’s likely right, especially if the pandemic, inflation, and supply chain issues remain relevant in the public debate. In fact, it’s been fascinating to watch the real-world response to Texas’s SB 8. While Twitter arguments rage and courtroom battles continue, the issue has seemed to trigger less cultural conversation than the controversies over Dave Chapelle’s Netflix comedy, and corporate activism has been muted.

The abortion rate continues to wane, and if negative attitudes about abortion persist, could the abortion debate end not with a giant legal and political bang—with huge numbers of Americans rallying for or against abortion rights and placing abortion at the center of American political life—but with an exhausted cultural whimper?

Outside of politics, Americans are making choices, and the direction of those choices is clear. American pregnancies are increasingly rare, and they are increasingly precious. There are many consequences to this significant cultural shift, but we might see one consequence already: The abortion debate is changing, and the intensity of the argument may not be as high as either side expects. In Virginia—with Roe in the crosshairs—voters responded with a yawn, not a roar.

One more thing …

Watch this space! Next week I’ll be linking to a trailer for the new Dispatch Good Faith podcast. Each week I’ll be co-hosting a new episode with my good friend, former pastor, and senior fellow at Fuller Theological Seminary, Curtis Chang.

You’ll love hearing from Curtis. He’s one of the wisest and most thoughtful people I know, and he’s one of the best at making theology accessible and discerning the deep truths behind cultural trends. I’m incredibly excited about this podcast. I’ll be blasting out the trailer on my Twitter feed and in my newsletter. Please click and subscribe when you can.

One last thing …

This is a great song by JJ Heller. It’s beautifully sung, and it speaks to the glorious presence of God in our daily lives. Please give it a listen:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.