Hi all,

We’re coming up on the one-year anniversary of the founding of the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, or CHAZ.

As I wrote last year, I loved CHAZ. It was a spontaneous radical anarchist community that shared a nickname with the sort of blue-blazered boarding school kid who uses “summer” as a verb and corrects the pronunciation of “Gstaad.”

What I loved about it was the way in which it beclowned the modern Rousseauians who find the basic foundations of civilization contemptibly artificial and unnecessary. They thought they could live in radical egalitarian tranquility and comity. And then nature—specifically human nature—said, “Nah, bruh.”

As I wrote back then, “It took activists less than 24 hours to discover that even their make-believe Duchy of Grand Fenwoke relies on the basic building blocks of any polity.” The first thing they did? Create borders—even though we’d been told for quite a while borders are retrograde and icky. Then they accepted open-carry firearms permissions—another supposed horror—because the CHAZzers needed to protect themselves. And so on. They even created smoking sections.

Still, the lack of serious self-policing and the absence of the actual police created some real problems. The CHAZ Wikipedia page, which mostly reads like the CHAZ Chamber of Commerce hired a publicist to write it, nonetheless notes:

The SPD police blotter page listed FBI-reported law-enforcement incidents in the area: 37 incidents in 2019, and 65 incidents through June 30, 2020. Crime in the area from June 2 to June 30 rose 525 percent over the same period in 2019. In addition to two homicides and two non-fatal shootings, the increase included narcotics use, violent crimes (such as rape, robbery, and assault) and increased gang activity.

You would like to think that this controlled experiment would have had the effect of reminding people that police exist for a reason. And I’m sure it did; the problem is that it didn’t remind the people who needed reminding. Indeed, it was right around this time that the whole “Defund the Police” bandwagon was barreling through the Democratic primaries and the media like a school bus without brakes. Just four days after the founding of CHAZ, the New York Times ran a piece by Mariame Kaba, described as “an organizer against criminalization,” titled “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police.”

The headline was telling, because some liberals in the media had started to realize that they were hurting Democrats by giving this inane idea so much oxygen. They tried to clean it up in real time, like mechanics trying to fix a car while it’s still moving. TV hosts would have activists on and say something like, “You don’t literally mean ‘defund the police’—that’s a right-wing smear. You mean ‘reform the police,’ or, ‘move some police resources to mental health and other social services.’” And then the activists would say, “Actually, we mean literally abolish the police.”

While Joe Biden managed to win in part by refusing to buy into this insanity, the message hurt Democrats down ballot across the country. As Biden himself said in a December meeting with civil rights leaders, “That’s how they beat the living hell out of us across the country, saying that we’re talking about defunding the police. We’re not. We’re talking about holding them accountable.”

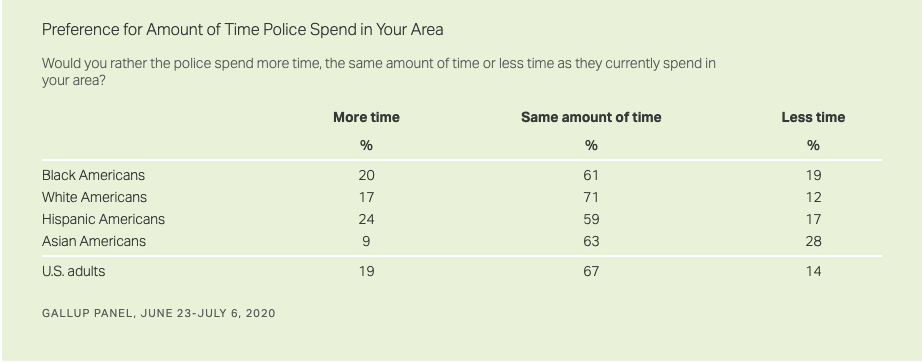

And here’s the thing: Calling for the abolition of the police should hurt Democrats—and any other politician or party that does it. I mean this in every conceivable way, but let’s start with the rank punditry: It’s an unpopular idea. Last summer, after months of “defund the police” agitprop from the media, Gallup asked normal Americans what they thought of the idea:

So 81 percent of black Americans and 83 percent of Hispanic Americans want cops to spend the same amount of time—or more—in their communities, which is just slightly lower than the total number for all Americans, which is at 86 percent.

Again, defunding the police will never, ever, get better press than it did last summer, yet more than 4 out of 5 Americans were clearly against it. Indeed, even this is misleading, because saying you want the police to spend less time in your community is not even close to the same thing as saying you don’t want the police in your community at all, never mind that you think it’d be totally fine if the police don’t come when your house is being broken into or you or your family is being attacked.

As a purely political matter, abolishing police departments is so effulgently idiotic that you’d have to be professor of social justice studies to think otherwise.

But it’s morally, logically, and philosophically asinine as well.

What the government is for.

I’m a limited government guy. I don’t want the government doing a lot of the stuff progressives—and many right-wingers these days—would like to see. But there is no definition of limited government that can countenance the idea of abolishing police entirely, because even if you strip government down to the studs, policing is what government is for. I’ll spare you lengthy quotes from Hobbes and Locke—or pretty much any sensible political philosopher who has ever existed—because this is an obvious fact of history and common sense.

What’s remarkable to me is how liberals have to keep relearning this idea. Crime is the enemy of everything liberals want the government to do. “Law and order” was central to getting Republicans elected president from 1968 to 1988. Bill Clinton understood this, which is why he ran explicitly as a law-and-order liberal. He even took time off the campaign trail to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a self-lobotomized black man so mentally deficient he told his guards that he was saving his pecan pie “for later” as they escorted him to the death chamber. Clinton was determined not to be seen as soft on crime in the way Michael Dukakis had been.

Crime—particularly violent crime—causes people to prioritize safety and security. This is a fact of human nature, and an entirely justifiable one. Get on the wrong side of that priority, and you can’t get elected to do the other stuff you want to use government for. This is because, again, government exists to protect people from violence and murder before literally anything else.

But for progressives, an interest in diminishing crime should go deeper than simply cynical electoral arguments. Crime hurts poor people far more than it hurts the affluent. This is true from every angle. Poor people are the victims of crime more than the non-poor.

We are not homo economicus, but sometimes it helps to think in economic terms. Writing in The Public Interest two decades ago, Eli Lehrer argued that we should think of crime as a tax, the burden of which is overwhelmingly carried by the poor:

For the 30 million or so Americans living in households earning less than $15,000 a year, crime represents a horrific fact of daily life. Compared to the middle class, the poor fall victim to nearly six times as many rapes, more than twice as many robberies, almost double the number of aggravated assaults, and half again more acts of theft. Crime is, in short, an inversely progressive tax.

Moreover, for a host of reasons, poor people have less capital—social, financial, political—to deal with the consequences of crime. Of course, it’s a bit gross to think of rape or robbery in crude economic terms. But it’s nonetheless true that well-off people can cope and rebound from the damage and trauma of crime better than poor people can—whether it’s in terms of replacing lost property, taking time off, or seeking psychological or physical therapy.

The consequences don’t end there. Here’s how a recent San Francisco Chronicle piece begins:

For years, John Susoeff walked from his home two blocks to the Walgreens at Bush and Larkin streets — to pick up prescriptions for himself and for less mobile neighbors, to get a new phone card, and to snag senior discounts the first Tuesday of the month.

That changed in March when the Walgreens, ravaged by shoplifting, closed. Susoeff, 77, who sometimes uses a cane, now goes six blocks for medication and other necessities.

“It’s terrible,” he said. On his last visit before the store closed, even beef jerky was behind lock and key. A CVS nearby shuttered in 2019, with similar reports of rampant shoplifting.

“I don’t blame them for closing,” Susoeff said.

Now, I don’t know whether Susoeff is poor, but it’s not hard to understand how this dynamic disproportionately hurts poor people.

A lot of people don’t understand that it’s more expensive to be poor in some fundamental ways. For instance, high crime neighborhoods aren’t attractive to big grocery chains. That means small shops, usually run by poor immigrants, are the only available sources of basic necessities. These stores have to charge more for all sorts of reasons, starting with the fact they can’t get the savings big chains get from buying on a huge scale.

Shoplifting in San Francisco is so rampant that Walgreens has shut 17 locations in the last five years. Theft in San Francisco-area Walgreens, according to the Chronicle, is 400 percent their national average. They spend 3,500 percent more on security guards than the norm. For CVS, 42 percent of losses in the Bay Area came from just 12 stores, comprising 8 percent of the market. The reasons for these surges are no doubt complicated, but California’s passage of Proposition 47—which reduced penalties on theft and increased the value of goods people could steal without being charged with a felony from $400 to $950—surely played a part.

The costs of such do-goodery get passed on to everybody, but most regressively and disproportionately to poor people. Just think about the complex relationship between housing costs and public education. People who can afford to move away from high crime areas tend to do just that. Local dollars fund public schools. And schools in poor areas, with high levels of crime, rob kids of opportunities.

And again, those costs aren’t just financial: Social scientists documented decades ago that crime fuels breakdowns in social trust, faith, and confidence in institutions, most notably in government. But it also undermined peoples’ faith and trust in each other. This makes society worse in tangible ways, even if some people don’t understand why:

Now, none of the above is an argument for turning a blind eye to police abuse or opposing criminal justice reform. There are reasonable arguments on all sides of these issues. But what isn’t helpful is the faddish nonsense that dominates the left’s contributions to the conversation about crime and punishment. Police aren’t modern day “slave patrols” committed to black genocide, nor is it “open season” on black men.

I know countless liberals who understand all of this. But by allowing the debate to be governed by radicals, activists, and Hollywood virtue signalers, they aren’t just making sensible reforms more difficult—they are helping people who have no interest in reform at all. And the more crime surges—as it is right now—the more perfectly rational voters who might be otherwise sympathetic to sensible reform will turn against them. The longer it takes for liberals to realize this, the more the burden of crime will fall disproportionately on the people they claim to care about most: poor people and minorities.

In 1952, Irving Kristol wrote about Joseph McCarthy, “there is one thing that the American people know about Senator McCarthy: He, like them, is unequivocally anti-Communist. About the spokesman for American liberalism, they feel they know no such thing.” Replace “anti-Communist” with “anti-crime,” and you can see the predicament liberals are making for themselves.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.