Dear Reader (especially those of you who know a Potemkin village when you see it),

It feels like a million years since we last corresponded.

I hate skipping columns and “news”letters for vacations, for the simple reason I am always more concerned that instead of coming back “refreshed” I’ll have forgotten how to make the word things go good.

Speaking of word things, I got a lot out of my conversation with Hyrum and Vernon Lewis on The Remnant before I left, and I have to say, between the conversation and their book, The Myth of Left and Right: How the Political Spectrum Misleads and Harms America, I’ve been revisiting a lot of my long-held views. Of course, this was often while snorkeling or drinking on a boat, but still. Their argument has stuck with me. And since I’ve been out of the news scrum for a bit, I’m just going to ruminate on this for a bit (at the cell phone parking lot at the Orlando airport).

Their argument, in brief, is that the political spectrum of “left” and “right” is a “social construct.” Nothing too controversial about that. Lots of things are social constructs, but are also in a very meaningful sense “real.” The law is, largely, a social construct. (I put “largely” in there to fend off 3,000-word emails from natural law zealots.) Paper money is a lie agreed upon. But because everyone agrees upon the value of paper money, paper money has real value. If you disagree, please send me all of your worthless currency.

But the Lewii go further (I think Lewii is a more euphonious pluralization that Lewises). They argue that left and right are not signifiers of a coherent or immutable set of ideas (ideology) or even sentiments (the “conservative temperament,” change vs. status quo, etc.), but are instead labels we use for groups—and that the ideas and orientations of those groups are a moving target. In other words, the causation is always backward from the way we think about these terms. What makes something left-wing or right-wing is entirely contingent on what left-wingers or right-wingers want at any given time, and any attempt to hold the definitions constant will fail.

For instance, they write:

Progressives were more likely to favor Prohibition, censorship, and racist eugenic policies than those on the right, and, by the standard measures of congressional ideology, segregationist Southerners were the most reliably left-wing members of the Democratic Party. Heroes of the “conservative” tradition, such as Alexander Hamilton, Henry Clay, and William Howard Taft, had far more enlightened racial views than their ‘liberal’ rivals Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, and Woodrow Wilson—showing that not even racial equality is an “essential” liberal principle. Issues considered “socially conservative” today were not associated with conservatism at all in the early twentieth century.

This is just a tiny snippet of their illustrations of their point. One thing the Lewii do not want for is examples that show left-wingers and right-wingers have switched positions and sentiments over the years. “Ultimately,” they argue, “we are saying that nearly all of the incessant talk about ‘liberal,’ ‘conservative,’ ‘progressive,’ ‘left wing,’ and ‘right wing’ is a lot of sound and fury signifying nothing.”

Now, I don’t disagree with them as much as many people thought I would. More significantly, I don’t disagree with them as much as I thought I would. Which brings me back to what I said above about revisiting a lot of my positions because of their indictment of left and right. “Revisiting” isn’t necessarily a synonym for “changing” my mind. As I look back on my copious writings about conservatism, I find a lot more confirmation of their argument, at least the soft version of their thesis.

What do I mean by “soft”? I think they make their case too stridently, too categorically. I don’t believe all of those labels signify nothing. That’s the hard version of their thesis. The soft version is that such labels, to one degree or another, mean much less than a lot of people believe. They are very persuasive about that. I have other caveats. For instance, when they say they’re fine with calling right and left “team red” and “team blue,” they run into a “rose by any other name” problem. But I don’t want to dwell on that. I want to dwell on, well, me.

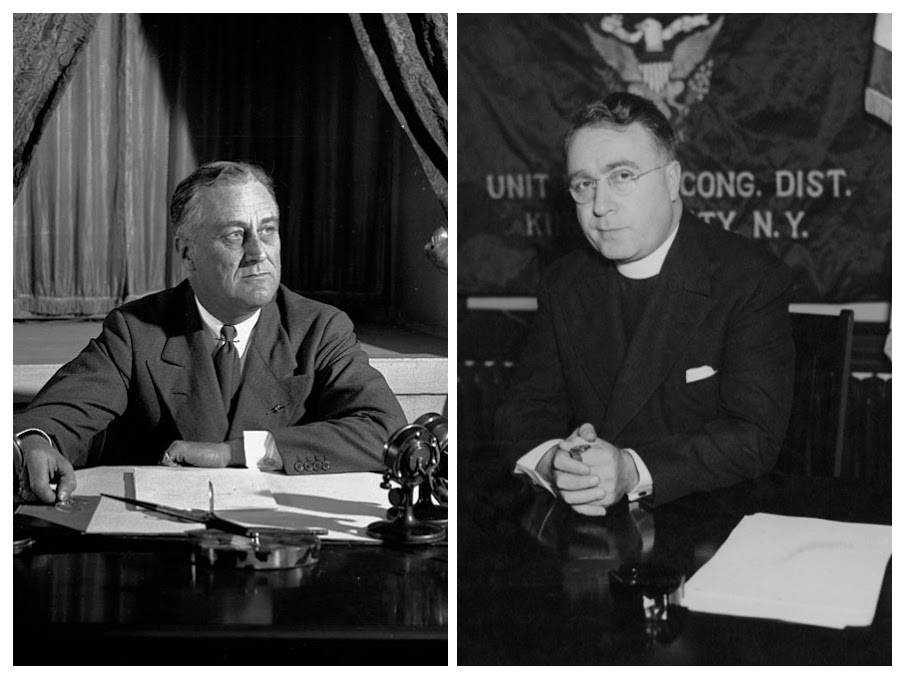

When I look back on a lot of my stuff, I’ve very often made a complementary, not contradictory, argument. For more than two decades, I’ve been writing about how a lot of things the left has claimed are definitionally right-wing aren’t inherently right-wing, and sometimes not right-wing at all. If you read Liberal Fascism you know I can do chapter and verse on this at great length. Father Coughlin is often described as the “right-wing radio priest” of the 1930s, when his entire program was to the left of FDR’s. He gets called “right-wing” because he was an antisemite. But antisemitism isn’t inherently right-wing. I’m not saying it’s inherently left-wing, either. As we’ve seen, the phenomenon manifests itself all over the ideological landscape.

Similarly, we’re often told that the right is the natural home of isolationism, but there’s a very long tradition of left-wing isolationism in America. Eugenics is widely described as right-wing, but most of the famous eugenicists were considered on the left. The “paranoid style” in American politics isn’t a right-wing thing, as countless historians, intellectuals, journalists, and pundits have claimed ever since Richard Hofstadter coined the term. The paranoid style is an American thing, and really a human thing, that manifests itself across the ideological spectrum at different times and places. Opposition to change, I’ve pointed out many times, is often a feature of left-wing politics—from opposition to things like GMOs, repealing Roe v. Wade, reforming Social Security, and, you know, capitalism. And support for change is often a defining feature of right-wing politics, from support for things like GMOs, repealing Roe v. Wade, reforming Social Security and, you know, capitalism.

Jacob Heilbrunn has a new book coming out, America Last: The Right’s Century-Long Romance with Foreign Dictators. I haven’t read it yet. But my initial reaction to the press release was, “Yeah okay. But this is the intellectual equivalent of one-hand clapping.” Because I could give you an outline of the left’s century-long romance with foreign dictators without even doing much googling. Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler (for a while), Castro, Mao, Pol Pot, Khomeini, Daniel Ortega, and Hugo Chavez all had cheering sections among American leftists at one point or another. Hell, look at the pro-Hamas spinning today and tell me again how the right is uniquely indictable for the charge of being soft on illiberalism (or antisemitism).

In short, it’s fine to ding right-wingers for their support of various authoritarians and totalitarians, but to argue that this is an essentially right-wing thing is cherry-picking. Maybe Heilbrunn anticipates this objection in the book, but there’s no indication of that in the press release, which informs us that, “The habit of mind is not really about foreign policy, however. As Heilbrunn argues, the Right is drawn to what it perceives as the impressive strength of foreign dictators, precisely because it sees them as models of how to fight against liberalism and progressivism domestically.”

This is almost literally my argument about left-wing infatuation with authoritarianism from Lincoln Steffens and Walter Duranty to Thomas Friedman. As New Deal intellectual Stuart Chase put it, “Why should the Russians have all the fun remaking a world?”

I think Lewis & Lewis would respond to this by saying I’m right but I’m not taking the point to its logical conclusion. Rather than focus on the left’s cherry-picking, I should realize that the cherry-picking itself is proof that left and right are conceptually meaningless save as journalistic descriptors of two different teams that change their views in an endless relativistic battle for political power. Indeed, if I wrote that book about the left’s love affair with dictators, Heilbrunn or someone else could make the same point about my cherry-picking. Moreover, by adhering to this dualistic view of all politics falling into the left-right spectrum, I’m part of a larger problem. By starting from the presumption the left is wrong, we on the right fall into the trap of opposing positions simply because the left is for them. And vice versa. It’s a form of popular-front thinking that puts the agenda of the team ahead of both principle and policy.

And they have a point. A very good point.

But I’ve spent 20 years complaining about popular frontism, on the left and the right, while still holding onto the left-right spectrum.

I still think these labels have some utility for reasons I got into on The Remnant and will no doubt get into again (and again and again). But I want to offer a (partial) solution to the very real problem they helpfully, if uncomfortably, illuminate. I don’t think they would entirely disagree with me, indeed I’m partly restating their argument, albeit to illuminate (one reason) why I think we can hold onto left and right while also acknowledging its severe limitations and drawbacks.

Moar labels!

In their book they criticize me for holding a “private definition” of conservatism. My response to that is that what they call a “private definition,” I call “defining my terms.” I think defining your terms is hugely important for several reasons, starting with simple intellectual and writerly clarity. If you’re going to call something fascist, racist, socialist, etc. you should be prepared to explain what you mean by such labels. And if you’re going to write a book about such things, you should spell out what you mean by such terms.

This gets to the heart of my complaints about left-wing and liberal historiography alluded to above, but also about liberal media bias. The left, I’ve written countless times, thinks it has a monopoly on political virtue and therefore starts from the presumption that anything they consider bad to be definitionally “right-wing,” or “racist,” “fascist” etc. Orwell got at this when he described the lazy tendency of political writers to use “fascism” as placeholder for anything not desirable. Again, you can fairly criticize the right for a similar tendency, but right-wingers don’t control higher education, the mainstream media, Hollywood, and other command posts in narrative formation.

But there’s another reason to define your terms. When you rely on the broad, dualistic, categories of left and right, without any further specificity, you’re going to sweep all manner of people, ideas, and institutions into a single bucket. And that’s a profound disservice.

The easiest way to illustrate this is just to note how the Trumpian right desperately and thirstily insists that simply by opposing Trump you’re a left-winger. But I could also point out (again) that the definition of right-winger in the 1930s was largely “opponent of FDR.” I’ve come to know countless liberals and progressives—my American Enterprise Institute colleague Ruy Teixeira comes immediately to mind—who think identity politics has been a disaster for the left. But if I call Ruy a “left-winger,”which he is by many standards, most people will assume that he agrees with Ibram X. Kendi, Noam Chomsky, or Rachel Maddow. If someone calls me a right-winger, a normal person who didn’t know anything else about me could reasonably assume I love Donald Trump. (If you’re new here, I do not love Donald Trump.)

In short, the problem isn’t using labels, the problem is not using more labels.

This is how language works. If I just say something is “hot,” I could mean everything from spicy, to sexy, to scalding, to popular. You need to use more words to communicate which meaning of hot you have in mind.

Think of it this way. A lot of people have tried to apply the equally flawed binary of “white” vs. “person of color” framework to Israel. Israel is cited by a lot of ridiculous people as a “white” or “European” “settler colonial” state. Among the myriad problems with this, Israel is not a particularly “white” or “European” country. Roughly half of Israelis are from the Middle East, North Africa, etc. The white/non-white binary erases Ethiopian, Moroccan, and other Jews. Such binaries make bad arguments easier for people who don’t want to do the work of making complicated arguments.

These days, sadly, “conservative” doesn’t convey very much information. Anti-Trump conservative conveys more information. “Classically liberal conservative” or “Reaganite conservative” conveys even more. Such qualifiers also convey different information than, say, “post-liberal conservative” or “nationalist conservative.” “American conservative” means something different than “French conservative” or “Bolivian conservative.” You get the point.

One of the things I like about bygone eras is how such qualifiers were much more necessary and widely used. I love all the old intramural fights between—in no particular order—American Trotskyites and Stalinists (but also Russian Trotskyites and Stalinists), ADL liberals and progressive (i.e. pro-Communist) liberals, Hamiltonians vs. Jeffersonians, Taft Republicans vs. Eisenhower Republicans, Buckleyites vs. Randians and Rothbardians, paleoconservatives and neoconservatives, paleoliberals and neoliberals, left libertarians versus right libertarians, Harry Jaffa vs., well, everyone.

I understand why the eyes of normal people often glaze over when hearing about such squabbles. It often sounds like rivalries between the Judean People’s Front and the People’s Front of Judea. But such granular labeling was useful because it helped illuminate important distinctions, not just of different principles but of different contests for power. Reducing everything to left versus right erases these distinctions intellectually and politically.

I’ve been rereading Lionel Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination, most famous for a single, often misunderstood, line in which he said, “in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.” In Louis Menand’s introduction to my edition, he writes, “In Trilling’s time, the division between liberal anticommunists and liberal anti-anticommunists, minor as it might appear from a historical distance (most anti-anticommunists were not pro-communist), seemed unbridgeable.”

The Cold War is over, but the culture war is raging. The problem is that a lot of the culture war—by no means all of it—is a caricature that plays out on TV and social media as a simplistic binary left-right conflict, when the reality on the ground is vastly more complicated and nuanced. The beauty and complexity of American politics prior to concretization of the left-right paradigm of the 20th century is that it relied on a mosaic of competing factions organized around multiple factions—economic, regional, religious, ethnic, etc. The parties were, for the most part, coalitions of these factions. The FDR coalition had communists, Jews, and blacks as well as Southern racists in it. Calling it left-wing illuminates some aspects of Roosevelt’s Democratic Party, but it obscures others. The only way to clear the fog is to employ more labels, not fewer.

A lot of people think that labels get in the way of progress. That was the argument behind “No Labels” when it first launched. Its credo back then was “Put the Labels Aside. Do What’s Best for America.” But, as I wrote about at length in my underrated second book, labels are vital to intelligent thought and basic survival. That’s because labels are another word for “words.” And without words, we’re back in the trees. Go into your kitchen and remove all the labels from your cleaning supplies and canned goods and see how much progress you make. I was just in Gainesville, Florida, where all the local ponds have signs warning about alligators. Such signs are truth-in-labeling. Would it be better if we put those labels aside?

Where the Lewii are correct is that the labels of left and right are insufficient. They’re the equivalent of replacing the poison warning on a can of bug spray or the alligator warning sign with “bad.” But it’s worse than that, because we live in a country where what is “bad” for Team Blue is “good” for Team Red. The only way past this problem is to explain, with more accurate labels, what we mean by good and bad. But that is too much to ask for a lot of culture warriors today who would rather use simplistic terms to do their thinking for them.

Various & Sundry

Canine update: My plane is about to take off, so I’ll be quick. The beasts have had a very nice time with Kirsten. Zoë did very well working security for a rotating roster of fluffballs and replacement spaniels, and she got to spend some quality time with Sammie, her bestest friend. Gracie has stayed at chez Goldberg with Clara, our housesitter who has been studying with Gracie (alas, pics of that are on The Fair Jessica’s phone). Clara has been amazed by how much Gracie likes—and demands—belly rubs. Anyway, I’m heading home and, hopefully, the welcoming committee will be half as excited to see me as I will be to see them.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.