Happy Wednesday! Quick reminder we’ve got a special bonus Dispatch Live on tap tonight. Our Advisory Opinions team will be answering your questions about the coming Supreme Court confirmation battle, and Sarah Isgur will talk to David French about his new book. Be sure to RSVP here, and we’ll “see” you at 8:30 p.m. ET!

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

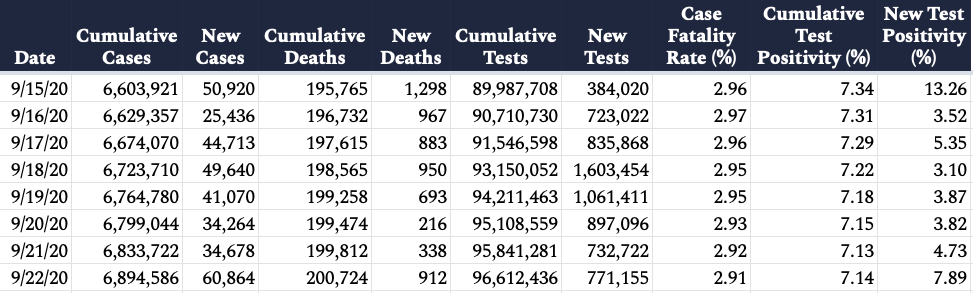

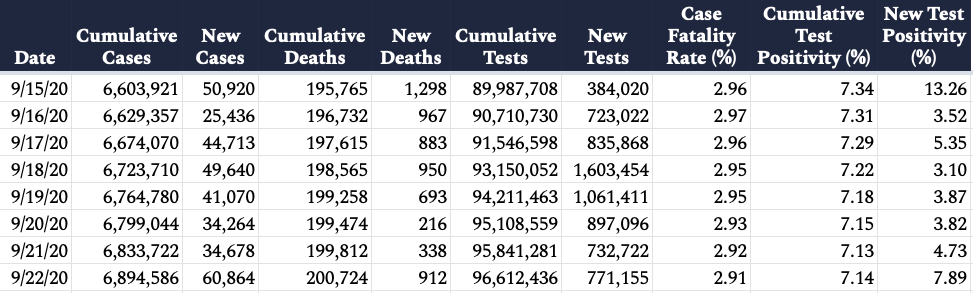

The United States confirmed 60,864 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 7.8 percent of the 771,155 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 912 deaths were attributed to the virus on Tuesday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 200,724.

-

Sen. Mitt Romney announced yesterday he intends to “follow the Constitution and precedent” and vote on President Trump’s coming Supreme Court nominee “based upon their qualifications.” His support for moving forward with the process increases the likelihood that President Trump’s nominee—set to be announced Saturday evening—will be confirmed to the court.

-

Slightly more than a week away from a potential government shutdown, the House approved a bipartisan short-term spending bill negotiated by Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin that will fund the government through December 11. President Trump is expected to sign the bill into law once it passes the Senate.

-

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ordered state election officials on Thursday to throw out “naked ballots” received by the election deadline, meaning any ballot not encased by the requisite “secrecy envelope” will automatically be invalidated. Lisa Deeley, the Democratic chair of the Philadelphia city commissioners, warned that the court’s ruling may require election officials to throw out more than 100,000 ballots, causing “significant postelection legal controversy, the likes of which we have not seen since Florida in 2000.”

-

The GOP plans to challenge the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s September 17 extension of the state’s mail in voting deadline, marking the first case the Supreme Court will likely hear in a post-Ruth Bader Ginsburg court. The Republican party of Pennsylvania filed court documents Monday night and Tuesday morning, setting the stage for a bitter election fight in the battleground state that Trump won by 44,000 votes in 2016.

The Norms, They Are A Changin’

When Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell made clear on Friday Republicans would be moving ahead with filling the Supreme Court vacancy left by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death, Democrats were—predictably—furious. “McConnell is cementing a shameful legacy of brazen hypocrisy,” Sen. Bernie Sanders said. Sen. Martin Heinrich called Republicans confirming a new justice “hypocrisy at its worst” and “a grave injustice to the American people.”

Minority Leader Chuck Schumer escalated the rhetoric on a Democratic caucus call the following day. “Let me be clear,” he said. “If Leader McConnell and Senate Republicans move forward with this, then nothing is off the table for next year.”

Well, by all accounts, Leader McConnell and Senate Republicans are moving forward with this, so it’s worth taking a look at the procedural maneuvers Schumer says are now on the table if Democrats reclaim the Senate in November. Neither are entirely without precedent, but both would usher in dramatic—and perhaps irreversible—change to our political system.

Packing them in.

The most direct path to vengeance for Democrats would be to pack the Supreme Court. Proposals that would do so have thus far taken two basic tacks: Ostensibly nonpartisan reform or straightforward score-settling in response to “stolen” seats of Justice Gorsuch and whoever replaces Justice Ginsburg. The plan Pete Buttigieg ran on in the Democratic primary, for example, falls into the former camp. He would expand the court from nine members to 15, with five associated with the Republican Party, five associated with the Democratic Party, and the remaining five having to be chosen unanimously by the first 10. New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie, by contrast, has argued for a more straightforward, “eye-for-an-eye” approach. “Add two additional seats to account for the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the Gorsuch and Kavanaugh nominations,” he wrote in 2019.

“Court packing,” the colloquialism for Congress using its (yes, entirely constitutional) power to add seats to the Supreme Court, isn’t new to U.S. politics. Congress has intervened to add—and subtract—justices under partisan conditions several times in American history. But the Supreme Court has stood at nine justices since 1870.

At the beginning of the 19th century, with President John Adams’ Federalist administration due to be replaced by Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican one in 19 days, Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801 (or “Midnight Judges” Act). The act reduced the number of Supreme Court justices from six to five (denying Jefferson a nomination), and created 16 new circuit judgeships, which Adams rushed to fill before leaving office; he was said to still be confirming circuit judges the night before Jefferson assumed the presidency, and his party’s actions were met with uproar. Jefferson and his own party repealed the act, and their refusal to seat nominee William Marbury would lead to the landmark Marbury v. Madison ruling that established judicial review. The Judiciary Act of 1802 restored the Supreme Court to six members, and the 7th Circuit Act of 1807 added another, bringing the total to seven. The 8th and 9th Circuit acts brought the total number of justices to nine in 1837.

Some 30 years later, the Civil War-era federal government added a 10th justice to both accommodate the rapidly growing population in California and aid the Lincoln administration in its war effort. After the war, radical Republicans in Congress—locked in a bitter feud with President Andrew Johnson over Reconstruction—used attrition to reduce the court’s size to seven, denying Johnson appointments. They later restored all nine justices under President Ulysses S. Grant.

America’s most well-known court-packing episode, however, came in the mid-20th century as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt attempted to ram through his myriad New Deal programs. Angered by conservative rulings of the “nine old men” on the court blocking some of his initiatives, Roosevelt proposed in 1937 to pack it—just not in so many words. He relied on a (somewhat valid) concern over inadequate pensions leading justices to stave off retirement, proposing full benefits to justices over the age of 70. If a justice refused to retire after that, he would appoint an “assistant” justice to the court. The idea was met with bipartisan blowback from both elected officials and the press, and never got far. But, for Roosevelt’s purposes, it ended up not mattering much: Justice Owen Roberts’ decision to accommodate more aspects of the New Deal—the famous “switch in time that saved nine”—as well as a later spate of retirements, largely removed the court’s threat to the New Deal.

Would Democrats actually go through with the move, or is the threat merely to gain leverage? Joe Biden has expressed hesitancy in the past. “I would not get into court packing. We add three justices. Next time around, we lose control, they add three justices,” he said in a debate last fall. “We begin to lose any credibility the court has at all.” Earlier this week, however, the former vice president refused to answer a question about the possibility. “It’s a legitimate question,” he said. “But let me tell you why I’m not going to answer that question: because it will shift all the focus. That’s what [Trump] wants.”

Sen. Kamala Harris, Biden’s running mate, did not rule out the possibility in an interview with Politico in March 2019. “We are on the verge of a crisis of confidence in the Supreme Court,” she said. “We have to take this challenge head on, and everything is on the table to do that.”

As of late last year, polling showed that trust in the institution of the Supreme Court remained relatively high. Nearly 70 percent of respondents in an Annenberg Civics Knowledge Survey trusted the Supreme Court to “operate in the best interests of the American people.” A Marquette Law School survey found 37 percent had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the court, with 42 percent having “some” confidence. (Only 10 percent and 28 percent had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in Congress and the presidency, respectively.)

Packing the Supreme Court would likely affect these numbers with one segment of the population, while confirming Justice Ginsburg’s replacement in the next few weeks would affect them with another.

Busting up the filibuster.

Former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid told CNN yesterday that, if Biden wins and Democrats take control of the Senate next year, the legislative filibuster is toast. It’s “not a question of if it’s going to be gone, it’s only when it’s going to be gone,” he said. And Reid would know: His decision to “nuke” the filibuster for most presidential nominations in 2013 opened the door for McConnell to do the same for Supreme Court nominees in 2017.

But Reid is probably right. Immense pressure is building on the left to do away with the procedural rule that allows a minority of senators to delay—or block—votes on pieces of legislation that may have majority support. If Senate Republicans confirm Justice Ginsburg’s replacement, “we must abolish the filibuster,” Sen. Ed Markey tweeted on Friday.

Biden has long opposed abolishing the filibuster—he himself made use of it during his years as a senator. “Ending the filibuster is a very dangerous move,” he told reporters in August of last year. But since wrapping up the Democratic nomination, he’s begun to hedge. “It’s going to depend on how obstreperous [Senate Republicans] become,” he said. “But I think you’re going to just have to take a look at it.”

There’s a misconception out there that the Senate filibuster is enshrined in the Constitution, or was established during the inaugural Congress—it wasn’t. The filibuster as we know it today “was, at best, an unintended consequence of cleaning up the rule book,” said Sarah Binder, a political scientist at George Washington University who focuses on the politics of legislative institutions. “You might even call it a mistake.”

When the Senate and House were created, they had similar rulebooks—and both chambers’ guidelines included a “previous question” motion, affording a majority the ability to cut off debate and move to a vote on a bill or resolution. The House’s rulebook still includes that motion; the Senate’s does not. Why? Because in 1805, then-Vice President Aaron Burr—he of killing-Alexander-Hamilton-in-a-duel fame—told senators their rulebook was cluttered and contained redundancies. The “previous question” motion was dropped the following year, and with it, the ability of Congress’ upper chamber to end debate with a simple majority.

The Senate eventually instituted a “cloture” rule in 1917 at the behest of then-President Woodrow Wilson (World War I necessitated some urgency), allowing debate to be cut off by a two-thirds majority. That threshold was reduced to three-fifths, or 60 votes, in 1975.

Like just about anything in politics, the filibuster comes with tradeoffs. “If you think that moderation is something to be strived for,” Binder said, “then the filibuster under some conditions has the capacity to rein in off-center ideas.” She added that, since the Senate majority isn’t always representative of the popular majority, the filibuster can also be “a check against majorities that may not quite be terribly representative.”

But with our two political parties as polarized as they are, “the ability to threaten filibuster more often than not leads to gridlock and stalemate,” Binder said.

Some would argue that’s by design. “The Senate’s treasured tradition is not efficiency but deliberation,” McConnell wrote in an op-ed last year. “One of the body’s central purposes is making new laws earn broader support than what is required for a bare majority in the House.”

“[The legislative filibuster] echoes James Madison’s explanation in Federalist 62 that the Senate is designed not to rubber-stamp House bills but to act as an ‘additional impediment’ and ‘complicated check’ on ‘improper acts of legislation,’” McConnell continued. “It embodies Thomas Jefferson’s principle that ‘great innovations should not be forced on slender majorities.’”

“It’s important to make sure the minority has an input in legislation because that’s how the Senate limits government power and keeps wild-eyed partisans in check,” Sen. Ben Sasse told The Dispatch. “The Senate is supposed to act deliberatively while the House acts quickly. Killing the filibuster would mean that 51-49 votes could dramatically swing public policy back and forth, creating more cynicism and distrust. The Senate needs to promote debate, not end it.”

But others see a dramatic swing back and forth as preferable to the present reality, in that it would force elected officials to actually put the grand ideas they campaign on to the test. “The promise of more responsive majoritarian governance is not that one side wins and never loses power again,” Ezra Klein said in his podcast with David French this week, “it’s exactly in fact what many people seem to fear about it: The promise of legislating from different directions at different times, such that the American people then get to see if they prefer once set of policies to the other, and then parties have to adjust based upon their preferences.”

It would prevent “why you can’t ever get anything done and why all of our problems endlessly go unsolved” from being “the only thing American politics is about,” he argued.

When Reid invoked the nuclear option and abolished the filibuster for non-Supreme Court nominees back in 2013, McConnell issued an ominous warning. “You’ll regret this, and you may regret this a lot sooner than you think.” Republicans won back the majority a year later and the White House two years after that, and have since installed about 200 of President Trump’s federal judge appointees.

Worth Your Time

-

Does the debt matter? According to Peter Wehner and Ian Tufts, neither party seems to think so. For decades, both Republicans and Democrats have piled trillions of dollars onto our national debt with little regard for how such fiscal irresponsibility will affect future generations. In National Affairs this week, Wehner and Tufts endeavor a solution out of this fiscal crisis we’ve found ourselves in: “Everything needs to be on the table — entitlement reforms, a restructuring of the tax code (including tax increases), changes to the federal budget process, etc. — to ensure that the United States can gradually bring the public debt down to more sustainable and safer levels.”

-

The U.S. coronavirus death toll officially surpassed 200,000 people this week, and the elderly accounted for the vast majority of those deaths. Research shows that “globally, people don’t value elderly lives as much as they do young people’s,” Olga Khazan writes in a piece for The Atlantic, citing a giant trolley problem-esque psychology study called the Moral Machine game. “When it comes to deciding who lives or dies, there’s a disregard for the elderly, even among the elderly.” This trend, Khazan argues, has made it far easier for the public to grow numb to the staggering loss of life we as a society have experienced these past six months.

-

Joe Rogan has one of the largest political followings in the country, with Spotify reportedly paying $100 million in May for the exclusive rights to broadcast his show. Rogan brands himself as a moderate liberal, but earlier this year he faced a tidal wave of backlash from Democratic elites after Bernie Sanders publicly acknowledged Rogan’s quasi-endorsement of his candidacy. “The argument was that Rogan’s views are so repellent, bigoted, and anathema to liberalism that no Democratic candidate should be associated with him,” explains Glenn Greenwald in The Intercept, citing Rogan’s history of questioning the modern trans-activist movement on his show. “If the standard is that anyone who even entertains debates over the maximalist and most controversial questions in this very new and evolving social movement is to be cast out as radioactive, liberalism and the Democratic Party will be a very small group.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

It’s become trendy on the American populist left and the nationalist right to blame the country’s problems on the alleged domination of libertarian elites in Washington. In his latest Capitolism newsletter, Scott Lincicome argues this claim is utter nonsense—and he has a zillion charts to prove it. From trade policy to the administrative state, “our current, mishmash system reflects the divided and often frustrating mix of views and procedures that is the United States.” This reality, Lincicome argues “is far more complicated (and boring) than the populist caricature, and it certainly doesn’t lend itself to easy solutions like purging Friedmanesque ideologues from the government.”

-

Over at the site today, Andrew has a piece breaking down the CDC’s recent head-scratching decision to publish new guidance calling the coronavirus an “airborne disease” spread via aerosols—and then to walk that guidance back, claiming it was published in error.

-

Also on the site today, Gregg T. Nunziata provides a brief history lesson and tutorial on the Senate confirmation process for Supreme Court justices. Did you know that on a few occasions in the past, the Senate confirmed the president’s nominee in an afternoon?

-

The SCOTUS wars are back in session and hypocrisy abounds on the political left and right. In yesterday’s French Press (🔒),David walks readers through the history and political norms surrounding election year Supreme Court nominations. “The decision to turn on a dime and reject clearly stated political principles when a presidential election is so close that voting is actually underway represents an escalation of the SCOTUS wars,” he writes. To save our country from irreparable political enmity, David argues Trump should make his pick and the Senate should wait to confirm until after the election. “If Trump wins, they confirm the pick. If Trump loses, they also confirm the pick unless key Democrats (including Joe Biden) pledge not to pack the court.”

-

David is back on The Remnant again, but this time as a guest, not a guest host! He and Jonah discuss his new book, Divided We Fall, and how we can knit together our social fabric back again. Don’t worry, they talk Tenet, The Boys, and Dune, too.

Let Us Know

A nine-justice Supreme Court and the legislative filibuster: Necessary structures to promote cautious and stable governance, or hopeless relics of a bygone era?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), James P. Sutton (@jamespsuttonsf), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.