Happy Thursday! Time for another round of “Is today the day the Supreme Court finally releases its ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and throws Declan and Esther’s TMD plans in the garbage?”

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

Moderna on Wednesday released new clinical data about a modified version of its COVID-19 vaccine designed to target both the original strain and the Omicron variant, claiming its trials show a 50-µg dose of the booster elicits a “potent” neutralizing antibody response against both. The company said it has already submitted the data to public health regulators, and hopes the shot will be authorized for use by August.

-

An earthquake with a magnitude of 5.9 struck eastern Afghanistan on Wednesday, reportedly killing more than 1,000 people and injuring at least 1,500 more, mostly in the country’s Paktia and Khost provinces. The casualty figures are expected to rise as search and rescue missions continue.

-

Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense said 29 Chinese aircraft—including six H-6 bombers—entered the island’s air defense identification zone earlier this week in the third-largest such incursion this year. The move comes days after Bloomberg reported the Biden administration had rejected China’s assertion that the Taiwan Strait is not “international waters.”

-

Testifying before the Senate Banking Committee on Wednesday, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell told lawmakers central bankers “do not think” they will need to provoke a recession to get inflation under control, but conceded that it’s “certainly a possibility” because achieving price stability is “absolutely essential” to the Fed.

-

The United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics reported Wednesday that the UK’s consumer price index (CPI) rose at a 9.1 percent annual rate in May, a 40-year high and up from 9.0 percent in April. The Bank of England projected last week inflation in the country would continue rising over the next few months until it peaks “slightly above” 11 percent in October of this year.

-

Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District Superintendent Hal Harrell announced yesterday the district’s police chief, Pete Arredondo, was placed on administrative leave as an investigation into the police response to last month’s shooting at Robb Elementary continues.

-

Rep. Bennie Thompson, chair of the January 6 Select Committee, told reporters Wednesday the committee will adjust its public hearing schedule after receiving more evidence about former President Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election, including new documentary footage and additional documents from the National Archives. The committee’s fourth hearing will still be held later today, but the series likely won’t resume until next month after the House’s 4th of July recess.

Religious Schools Maine Attraction at Supreme Court

What comes to mind when you think about Maine? Lobsters? Lighthouses? Former toothpick capital of the world?

Probably not that last one. But you may know the state is sparsely populated—shy of 1.4 million residents despite having a single county bigger than Connecticut and Rhode Island combined. (One of your TMDers grew up in Maine and has a lot of wicked good fun facts to squeeze in.)

Those 1.4 million people are spread out, so many school districts don’t have enough kids to support a middle or high school. Instead, the districts send students to neighboring public schools or give parents of eligible students money for tuition at any accredited, non-sectarian private school they choose.

Which brings us to the other thing that might come to mind this week when you think about Maine (right after you remember that it saw the first naval battle of the Revolutionary War): The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 on Tuesday in Carson v. Makin that the state can’t exclude religious schools—sectarian schools—from the tuition assistance program.

The Court has already been revisiting the question of how the First Amendment applies to government funding and religious institutions. In 2017’s Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer, it ruled that Missouri couldn’t exclude a church from a program to improve playground safety on the grounds that it was a religious institution. In 2020’s Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, the Court ordered Montana to include religious schools in a tax credit-funded private school scholarship program.

This ruling takes the next step, arguing Maine can’t block eligible parents from using tuition money at schools that teach religion. “There is nothing neutral about Maine’s program,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority opinion. “The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools—so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion.” He noted that secular private schools eligible for the program are different from public schools in meaningful ways—such as curriculum and teacher certification—so the existing block on religious schools can’t be justified on grounds that the state is otherwise filling its gaps with an education equivalent to that of a public school.

The court’s three Democrat-appointed justices dissented. “This Court continues to dismantle the wall of separation between church and state that the Framers fought to build,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote.

“We have never previously held what the Court holds today, namely, that a State must (not may) use state funds to pay for religious education as part of a tuition program designed to ensure the provision of free statewide public school education,” Justice Stephen Breyer added in his dissent. “Does that transformation mean that a school district that pays for public schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to send their children to religious schools?”

No, Roberts argued—Maine could drop its private subsidies and stick with public schools. “A state need not subsidize private education,” he wrote. “But once a state decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious.” Indeed, a campaign sponsored by several groups including the Education Law Center and the Southern Poverty Law Center promised Tuesday to push Maine to drop the program altogether. Roberts suggested alternative (if not terribly realistic) solutions for Maine’s scanty school problem—opening more public schools, remote learning, busing kids farther, founding public boarding schools.

Breyer also suggested that the majority opinion violates the Establishment Clause, which forbids the state from favoring any one religion. “Maine denies tuition money to schools not because of their religious affiliation, but because they will use state funds to promote religious views,” Breyer wrote. “The very point of the Establishment Clause is to prevent the government from sponsoring religious activity itself, thereby favoring one religion over another or favoring religion over nonreligion.” But Roberts would argue his opinion does no such thing: Maine parents will be under no obligation to use the tuition benefit at a school espousing a particular religion, or at a religious school at all. Those who wish to pursue secular education for their children will still be able to do so.

The ruling also doesn’t preclude states like Maine from establishing certain criteria schools must meet to be eligible for the tuition subsidies. “The state remains free to restrict vouchers to schools that fail to meet curricular standards that apply equally to both religious and secular schools—even if those standards go against the beliefs of some of them,” George Mason University law professor Ilya Somin argued. “For example, it might require recipient schools to teach students the theory of evolution despite the fact that some religious groups reject it.”

Amy and David Carson—two of the parents who brought the suit in 2018—put their daughter Olivia through high school at a Christian school on their own dime, but celebrated the ruling this week anyway. “We are overjoyed that today’s decision will allow Maine families to choose the school that is best for their child,” Amy Carson said. “We always knew that we would be unlikely to benefit from a victory but felt strongly that Maine’s discrimination against religious schools and the families who choose them violated the Constitution and needed to end.”

Biden’s Mixed Messages on Oil

Asked by a reporter about his strategy for an upcoming boxing match with Evander Holyfield, Mike Tyson famously responded that “everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Joe Biden was no Elizabeth Warren, but he had plenty of plans as he was running for office in 2020. Plans to bring about a “Clean Energy Revolution” and transition the United States away from fossil fuels entirely by “no later” than 2050. Plans to ban new oil and gas permitting on public lands and waters. Plans to “get every major country to ramp up the ambition of their domestic climate targets.” Plans to make Saudi Arabia a global “pariah” and ensure the kingdom “pays the price” for its myriad human rights violations.

Then, he got punched in the mouth. First by $3.50-per-gallon gas. Then by $4.00-per-gallon gas, $4.50-per-gallon gas, and $5.00-per-gallon gas. And as the cost of filling up a tank continues to increase—up more than 50 percent since the beginning of this year, and more than 80 percent since the comparable pre-pandemic world of June 2019—Biden’s political prospects grow darker. Voters routinely list inflation—and specifically gas prices—as the biggest issue currently facing the country, and they fundamentally don’t trust the president to address it. Correlation doesn’t necessarily equal causation, but Biden’s net approval rating has fallen from -8.6 percent in mid-March to -15.1 percent today.

That rapidly shifting political reality has led to some cognitive dissonance. At different points during his campaign and presidency, Biden has both guaranteed his administration will “end fossil fuel” and written letters to oil executives asking them to “take immediate actions to increase the supply of gasoline, diesel, and other refined product.” He has both signed executive orders attempting to pause new oil and gas leases on public lands and chastised oil and gas companies for not drilling more. Last week, Biden convened a meeting of international leaders to discuss efforts to limit global emissions and accelerate the transition to clean energy. Next month, he’ll visit Saudi Arabia in an effort to convince the Kingdom to boost its oil production.

No wonder the energy sector is confused. “I think the industry is just waiting for security, for consistency, to be able to invest. That’s all business needs,” Leslie Beyer—CEO of the Energy Workforce & Technology Council, which represents more than 450 companies in the oilfield services and equipment sector—told The Dispatch. “We aren’t able to invest as much as we would like. All the administration would need to do is just give us some visibility and some stability.”

In a typical market, soaring prices for a good encourage businesses to increase production of that good and reap higher profit margins until supply and demand rebalance at a new equilibrium. Biden himself touted the concept in a letter to oil executives last week, arguing crude oil prices above $110 per barrel should serve as “ample market incentive” for companies to boost their output. Some have done so on the margins—Exxon and Chevron responded to Biden’s letter reiterating their plans to increase production in the Permian Basin this year—but not by anywhere near as much as $110-per-barrel crude would ostensibly suggest.

Why? Because that’s not the price off of which companies are making these determinations. Boosting output requires significant capital investment and months of lead time—expectations of what prices will be in the future are much more pertinent to companies’ decision-making than the current rates. And after being burned by oil price crashes on multiple occasions over the past decade, producers have become much more risk-averse when it comes to breaking ground on new projects. “The industry’s been totally focused on spending discipline [for the past two years], and it turned in stellar financial performance last year as a result,” said Ben Cahill, a senior fellow in CSIS’ Energy Security and Climate Change Program. “It was the first time in a decade that the industry found a winning formula for investors. And that’s the reason why growth is more restrained.”

To incentivize expansion, then, policymakers need to convince oil companies it’ll be worth their while not just today, when supply shocks have driven prices through the roof, but in the future as well. They could do so by giving producers the option to sell to the federal government at a fixed rate to restock the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, as Skanda Amarnath and Arnab Datta argued in a recent white paper for Employ America, a macroeconomic policy think tank. And they could also do so, Beyer added, by backing off their publicly stated desires to eventually put these companies out of business. “The administration has vilified this industry, really at every turn,” she said. “[By saying] they are not a good long-term investment, that restricts their access to the capital markets, which is what they need to be able to produce. It creates a vicious cycle.”

The administration has thus far eschewed these approaches, opting instead to pursue (likely unsuccessfully) what Amarnath described in an interview as more “gimmicky” proposals that will do little to either increase supply or decrease demand, like suspending the federal gas tax for three months, banning oil and gas exports, and implementing a windfall tax on oil company profits deemed “excessive.” And in the same press briefing on Thursday in which she called on oil and gas companies to boost production, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm reiterated her belief that the United States is “overly reliant” on fossil fuels and “must move to a clean energy future.”

“I don’t think the administration still quite gets it,” Amarnath told The Dispatch. “If they want a strong economy, they’re going to have to think about these problems realistically, and I don’t think that that has been the case thus far. They’re a little too worried about political convenience, and that’s gotten in the way of substance.”

Worth Your Time

-

Russia hasn’t had major cyberattack victories since it began invading Ukraine, Microsoft reports, but it’s not for lack of trying. “Moscow conducted more cyberattacks than was realized at the time to bolster its invasion, but more than two-thirds of them failed, echoing its poor performance on the physical battlefield,” David Sanger and Julian Barnes report in The New York Times. “In many instances, Russia coordinated its use of cyberweapons with conventional attacks, including taking down the computer network of a nuclear power plant before moving in its troops to take it over.” But Russia is still pushing disinformation. “Microsoft tracked the growth in consumption of Russian propaganda in the United States in the first weeks of the year. It peaked at 82 percent right before the Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, with 60 million to 80 million monthly page views. That figure, Microsoft said, rivaled page views on the biggest traditional media sites in the United States.”

-

Why do we sometimes get irritated even with the most un-sanctimonious do-gooders? And if we’re the do-gooders in question, how do we avoid driving everyone around us crazy while sticking up for what we think is right? In The Atlantic, Michelle Nijhuis offers some research-backed advice for our better angels. “Researchers have found that people face up to and address their moral inconsistencies when they consider themselves capable of improvement,” she writes. “Moral rebels can bolster this confidence [by] presenting their own behavior as the result of an ongoing process instead of an overnight transformation. Those who devote time to a political issue, for instance, might describe the small but meaningful wins that keep them motivated. Those who have given up a pleasure or convenience for ethical reasons might admit to occasional lapses or temptations. (Instead of ‘Meat makes me gag,’ vegetarians might try ‘That smells so good—steak’s the thing I miss the most.’)”

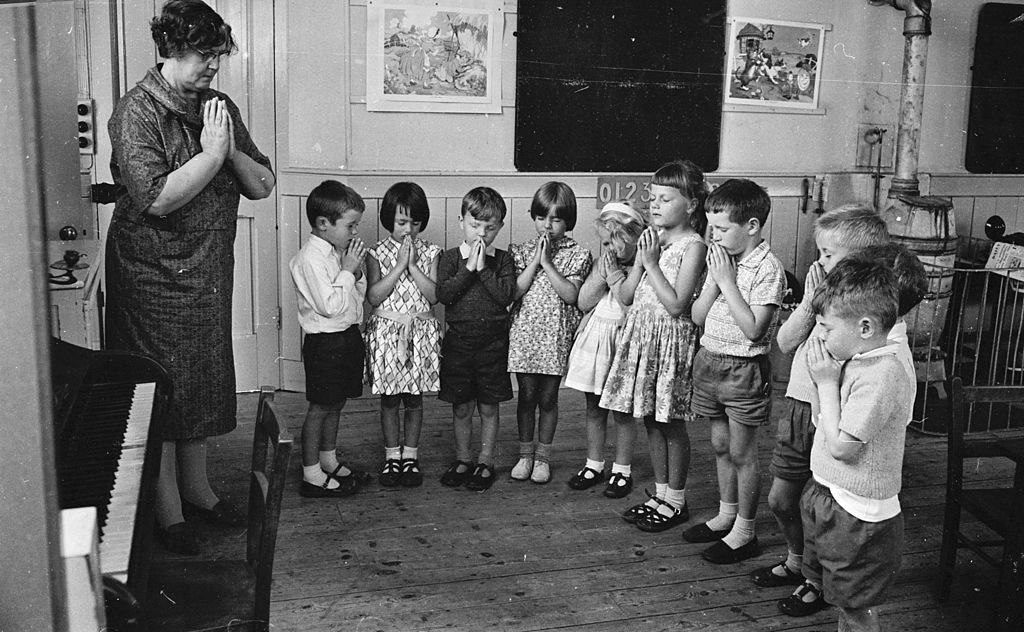

Presented Without Comment

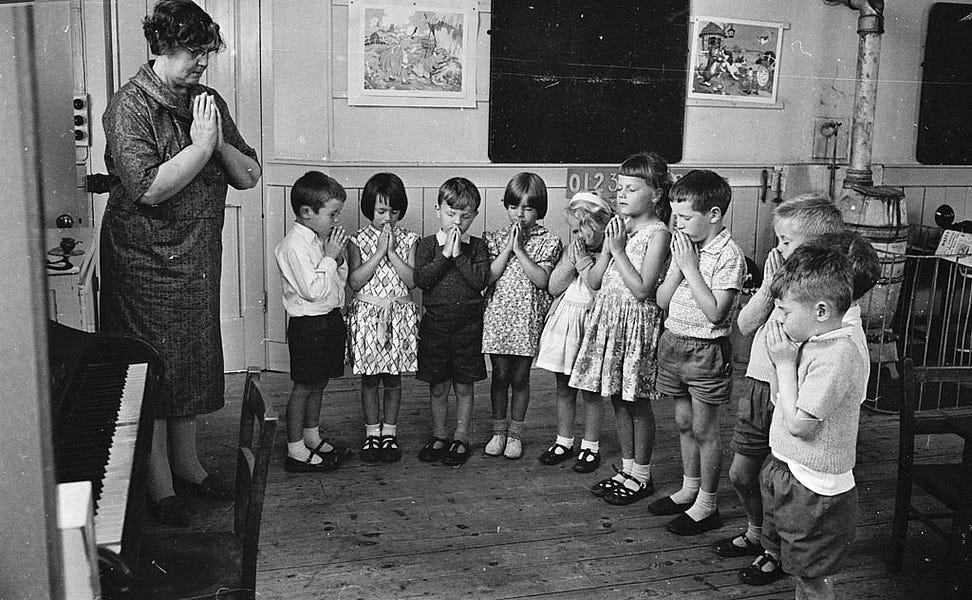

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

For more on the Biden administration’s contributions to rising gas prices, check out this week’s Capitolism (🔒). “Nobody is investing in new U.S. refinery capacity or even keeping up old refineries because they don’t think their investments will pay off,” Scott writes. “In the United States at least, policy—and policy uncertainty—is likely playing a role in the lack of new investment.”

-

Wednesday’s G-File (🔒) points out that John Dean is not the Watergate hero that everyone now remembers, with Jonah arguing it does a disservice to acts of modern political bravery to compare them to Dean’s actions. “It was only when things started to come apart that [Dean] turned on his former conspirators, told Nixon that Watergate was a ‘cancer on the presidency,’ and cut a deal for himself,” he notes. “If the Trump White House had John Deans instead of Pat Cippollones and Bill Barrs, it’s not obvious to me that Trump wouldn’t have gotten away with it.”

-

Commentary’s Christine Rosen drops by The Remnant today for a conversation with Jonah about the harmful effects of social media on young people, how pornography should be regulated, and the rapid spread of transgender ideology. Why has trauma become a political tool? How can epigenetics explain political problems?

-

And on today’s episode of The Dispatch Podcast, Declan spoke with Energy Workforce & Technology Council CEO Leslie Beyer and Employ America Executive Director Skanda Amarnath about gas prices. Why aren’t oil companies heeding Biden’s call to produce more? Is there anything the administration can do at this point to ease the pain at the pump?

Let Us Know

Which side of the Carson argument do you find more persuasive?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.