Happy Monday. At least in D.C., we’re now squarely in the thick of spring allergy season. Not ideal when incessantly on high alert for any respiratory symptoms.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

As of Sunday night, there are now 337,620 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States (a 37.7 percent increase from Thursday night) and 9,643 deaths (a 61.2 percent increase from Thursday night), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 2.9 percent (the true mortality rate is difficult to calculate due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 1,762,032 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States, 18.9 percent have come back positive, per the COVID Tracking Project, a separate dataset with slightly different topline numbers.

-

The Supreme Court canceled oral arguments for the nine cases it was scheduled to hear the rest of this term. The justices are still doing business relating to cases they’ve already heard, and are exploring alternatives to hearing cases in person.

-

President Trump fired Michael Atkinson—the intelligence community inspector general—late Friday night. Atkinson had flagged the Ukraine whistleblower’s complaint last fall. He released a remarkable statement about his dismissal on Sunday.

-

After becoming the first world leader to be diagnosed with coronavirus, Boris Johnson was hospitalized on Sunday because his symptoms have not abated even after 10 days.

-

An Associated Press review of federal purchasing contracts found “federal agencies largely waited until mid-March to begin placing bulk orders of N95 respirator masks, mechanical ventilators and other equipment needed by front-line health care workers.”

Wherefore Hydroxychloroquine

“I may take it.”

Over the weekend, President Trump repeatedly touted a drug called hydroxychloroquine as a possible treatment for COVID-19, noting that he had heard that people with lupus and those in malaria-prevalent countries who take the drug are not susceptible to the virus. “Maybe it’s true, maybe it’s not. Why don’t you investigate that?” he said to the reporters gathered in the briefing room Saturday.

While Trump has said the drug could be a “game changer,” Dr. Anthony Fauci and other medical experts have been more circumspect. Asked about it last week, Fauci said, “bottom line is there is no proven drug that has efficacy against this disease.” And when a reporter at the White House asked Fauci what he thought of the drug again last night, the president instead stepped in and said, “I answered this 15 times; you don’t have to answer.”

The differences between Trump and Fauci on hydroxychloroquine have been evident at the briefings for more than two weeks. When Trump lashed out at NBC’s Peter Alexander on March 20, he did so after Alexander asked about drugs to treat coronavirus. After Trump said he came from a “very positive school” on drug treatments and suggested a “game changer” might be coming, Alexander asked about Fauci.

“Dr. Fauci said that there is no magic drug for coronavirus right now, which you would agree. I guess on this issue—”

Trump interrupted: “Well, so, I think we only disagree a little bit. I disagree. Maybe, maybe not. Maybe there is, maybe there isn’t. We have to see. We’re gonna know.”

A report from Axios’ Jonathan Swan Sunday evening, later confirmed by the New York Times and others, detailed a confrontation between Trump trade adviser Peter Navarro and Fauci on the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine. The drug has been repeatedly touted by Trump advisers outside the administration, including Rudy Giuliani, Sean Hannity, and Dr. Mehmet Oz. But many medical experts are not convinced. “I’m not that optimistic about hydroxychloroquine,” said Scott Gottlieb, former head of the Food and Drug Administration under Trump. “It’s not really clear it’s having a clinical effect. I hope it works, but I think a lot of the enthusiasm is because it’s available, so people are over-interpreting the data, because it’s on the shelf.”

Hydroxychloroquine first came on the market as a drug used to prevent and treat malaria, but since the 1940s, it has also been used to treat autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus. It is not clear why it works on these autoimmune diseases, but the American College of Rheumatology explains that “[i]t is believed that hydroxychloroquine interferes with the communication of cells in the immune system.”

This also isn’t the first time that researchers have looked at hydroxychloroquine to combat viruses that target the respiratory system. During the SARS-CoV outbreak 15 years ago, the drug showed some promise “but it failed to decrease viral load in mice, and clinical interest drifted away,” explained one doctor.

The debate around its current efficacy revolves around several studies and what Fauci has repeatedly called “anecdotal evidence.” In mid-March, France published a study involving 36 patients who had tested positive for COVID-19 with varying severity of symptoms. Despite its small sample size and problems with its methodology, the reported results “showed a significant reduction of the viral carriage … compared to controls, and much lower average carrying duration than reported of untreated patients in the literature.”

But just days later two “blinded, randomized, and controlled” studies came out of China in which one “showed no effect” and the other “showed significant improvements in comparison to the controls in fever, in cough, and in pneumonia.” The French then followed up with another study which also showed “no evidence of a strong antiviral activity or clinical benefit of the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for the treatment of our hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19.”

Now, the U.S. has several clinical studies underway, including one conducted by the Henry Ford Health System that is working with 3,000 volunteers “from health care and first responder working environments.”

In the meantime, there has been a run on hydroxychloroquine because “many hospitals in the United States have simply been giving hydroxychloroquine to patients, reasoning that it might help and probably will not hurt, because it is relatively safe.” The president announced over the weekend that the U.S. currently has 29 million doses in the Strategic National Stockpile and that he had spoken to Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, who had previously banned all exports of hydroxychloroquine, to import more doses.

But hydroxychloroquine is just one of several drugs currently under testing for treatment of coronavirus. Drugs named Favipiravir and Remdesivir, both of which work to inhibit the virus’ replication, also have studies underway and have shown some preliminary positive results. And studies on Kevzara, a rheumatoid arthritis treatment, are underway in Italy, Spain, Germany, and France.

How Will We Catch Up On Testing?

Over the past month, the United States has undeniably ramped up its coronavirus testing efforts dramatically. We were slow off the blocks, and there have been undeniable speed bumps and complications, but it’s worth acknowledging that going from the roughly 2,000 tests performed in the U.S. at this time last month to the approximate 1.7 million tests we’ve administered now has been no mean feat.

The only problem: The virus got a head start, and it’s been growing just as fast as our testing efforts have. “If we’re doubling our test production every week, but we’re doubling our number of cases in the country every two to four days, we’re never going to catch up,” one doctor told us last week.

In a piece up on the site this morning, Andrew has a rundown of many of the challenges we still face in solving the primary epistemological problem of our ongoing pandemic: how many of us have had the thing, and who, and where. Here’s a quick rundown of the highlights.

Why can’t our testing catch up with the virus?

Apart from the brute mathematical problem of a virus growing exponentially and virus tests failing to do the same, the current test we’re using across most of the country to diagnose COVID-19 has some substantial drawbacks. The current tests rely on a process called polymerase chain reaction, in which viral RNA is duplicated millions of times until there’s enough of it that the lab can detect it. These tests are relatively labor-intensive on the laboratory side, which has led to a substantial backlog of kits awaiting testing at many U.S. labs. They also return a worrying number of false negatives, where the coronavirus is not detected in a person who is indeed sick.

The bigger problem, however, is simply that we’re still testing primarily people who are showing severe symptoms of the virus—and with substantial spread occurring in people with mild symptoms or even no symptoms at all, that means we’re still constantly toiling in the wake of the disease, not getting out in front of it.

What can we do to change that?

Continuing to ramp up the PCR testing regime remains useful for a few reasons, not the least of which is the hope that social distancing will slow the spread of new infections until testing can catch up. The best-case scenario is that we get to where South Korea was a few weeks ago: having enough knowledge of the current whereabouts of the virus, and enough tests on hand, to be able to aggressively test anyone known to have come into contact with any known coronavirus patient. We’re still a long ways from that point, however, and the biggest factor in getting there has little to do with testing at all: Rather, it’s simply hoping that keeping everybody away from everybody else will be enough to slow the spread.

Is there any fruitful testing that can be done in the meantime?

Actually, yes—although testing of a different kind. Over the last few days, a few private labs and the CDC have begun to roll out a new kind of coronavirus test, called a serology test. Serology tests don’t check for the presence of the coronavirus itself; rather, they analyze a blood sample for antiviral antibodies, evidence that a person has previously come into contact with the virus.

From an individual medical perspective, the serology test is less useful than the PCR test: There’s a period of lag after infection before the body starts producing antibodies, meaning the test is more reliable to determine who has had the coronavirus than it is to determine who has it. By the same token, a serology test offers no information about whether a person is still “shedding” the coronavirus—in other words, whether they remain contagious.

But from a public health standpoint, these tests could prove incredibly useful in finally revealing to us how widespread coronavirus infection has become—which could have a dramatic impact on how quickly we’re able to reopen much of our economy.

“It’s really important from a population health standpoint, and could give us tremendous clarity and visibility of what’s going on,” Dr. Howard Forman, a health policy professor at Yale, told The Dispatch. “Because it would completely change our policies and how we manage things if we were to discover that New York City, 30 percent of the population is positive for antibodies… If it’s five percent, then the game’s very different. Everything’s back to where we were. We have to keep things pretty hard locked down for a while.”

Worth Your Time

-

It’s a bit wonky, but a team of economists and researchers at Yale took a look at the “masks for everyone” question, and found “the benefits of each additional cloth mask worn by the public are conservatively in the $3,000-$6,000 range due to their impact in slowing the spread of the virus.” Their conclusion: “We must both encourage universal mask adoption and deal with the urgent policy priority that front-line healthcare workers face shortages of personal protective equipment, such as N95 respirators and surgical masks.”

-

President George W. Bush read John Barry’s The Great Influenza back in 2005, and grew concerned that a pandemic like the 1918 Spanish flu would one day strike the United States. Matthew Mosk has a piece for ABC News on how Bush’s concerns were subsequently converted into the infrastructure of what is now the basis of our coronavirus response.

-

Bill Withers—the iconic soul singer behind songs like “Lean On Me” and “Ain’t No Sunshine”—passed away on Friday at the age of 81. Take a moment to watch his rendition of “Lovely Day,” and try your best to have a Lovely Day yourself.

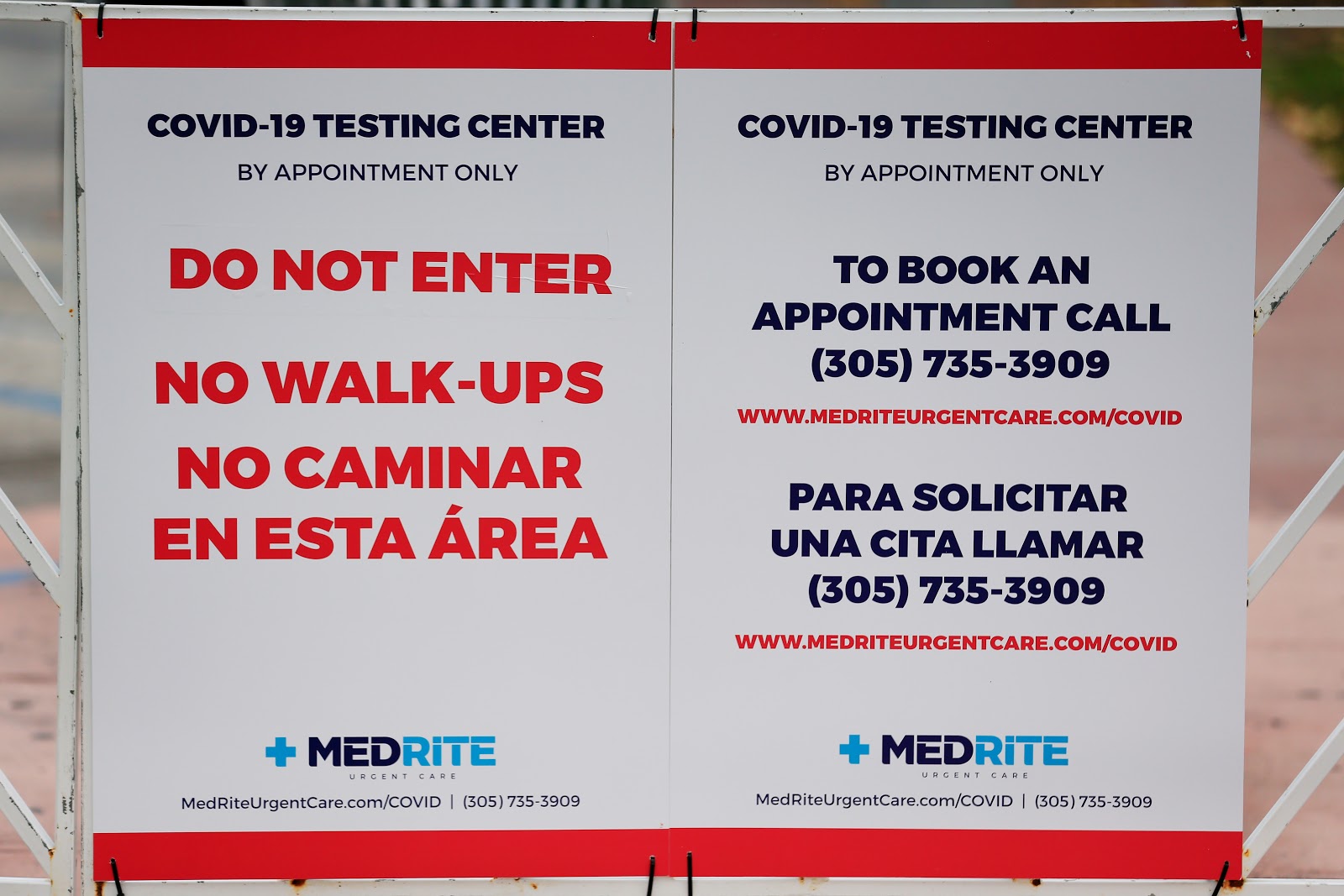

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Something Fun

Curious how your favorite television characters would respond to the coronavirus pandemic? Vulture asked the creators and writers of popular shows to write a synopsis of what a COVID-19-related episode would look like.

While Parks and Rec’s Ron Swanson “would be thrilled because now there’s a reason for him to be alone with no one bothering him,” Elmo’s parents are setting up Zoom so he “can have virtual playdates with all his friends” on Sesame Street.

Toeing the Company Line

-

Jonah’s latest G-File focuses on work, and the meaning therein. First, he reminds us how appreciative we should all be of workers on the frontlines getting the rest of us through this crisis: doctors and nurses, yes, but truck drivers, grocery store cashiers, delivery men and women, etc. “Take two seconds to think about what life would be like right now if these people weren’t out there,” he writes, before turning to the importance of “earned success.” Money matters, but so does the feeling of accomplishment that comes with a job well done: “People want to feel needed, that if they disappeared tomorrow they’d be missed.” He expands on these ideas (and much more) in his yet-to-be-named audio version of the newsletter.

-

If you missed David’s French Press yesterday, now’s your opportunity to rectify that. He drew on his experience as a JAG officer in Iraq to write about walking through the valley of the shadow of death, and offered some guidance for these coming weeks: Find your band of brothers (and/or sisters); find and pursue your purpose; seek joy; have faith.

-

On the website today, Jeryl Bier looks at the confusion caused when media outlets, reporting on a study that showed 1 million U.S. coronavirus patients might require ventilators over the course of the pandemic, suggested that the U.S. might need 1 million ventilators

Let Us Know

For a variety of reasons—not least of which China’s obfuscation—many American elected officials (in both parties), media organizations (including us at TMD), businesses, etc. were slower than they could have been in treating COVID-19 with the urgency it deserved.

Our question: When did the gravity of the coronavirus pandemic click for you, and what convinced you?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Alec Dent (@Alec_Dent), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.