Happy Wednesday! Three more TMDs until the weekend.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

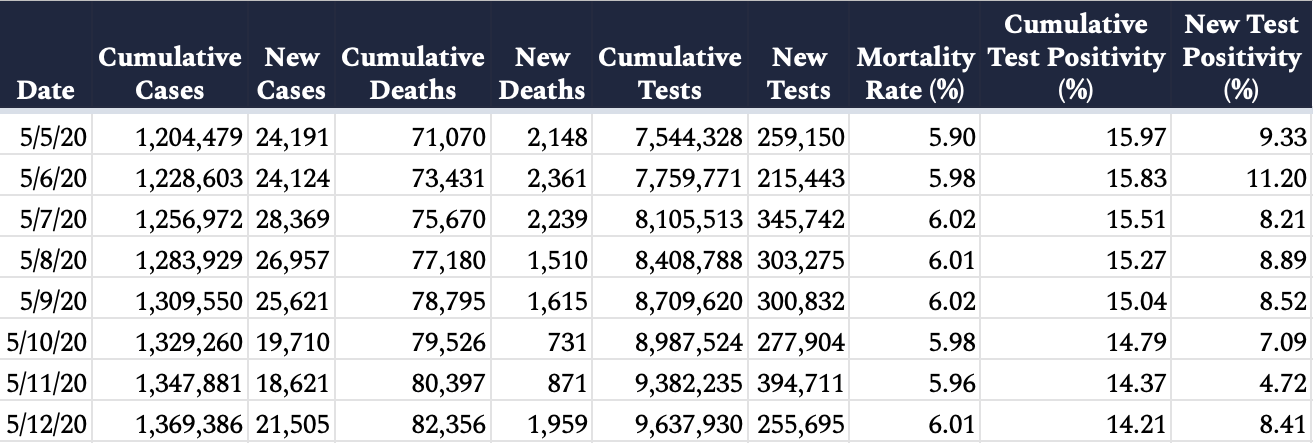

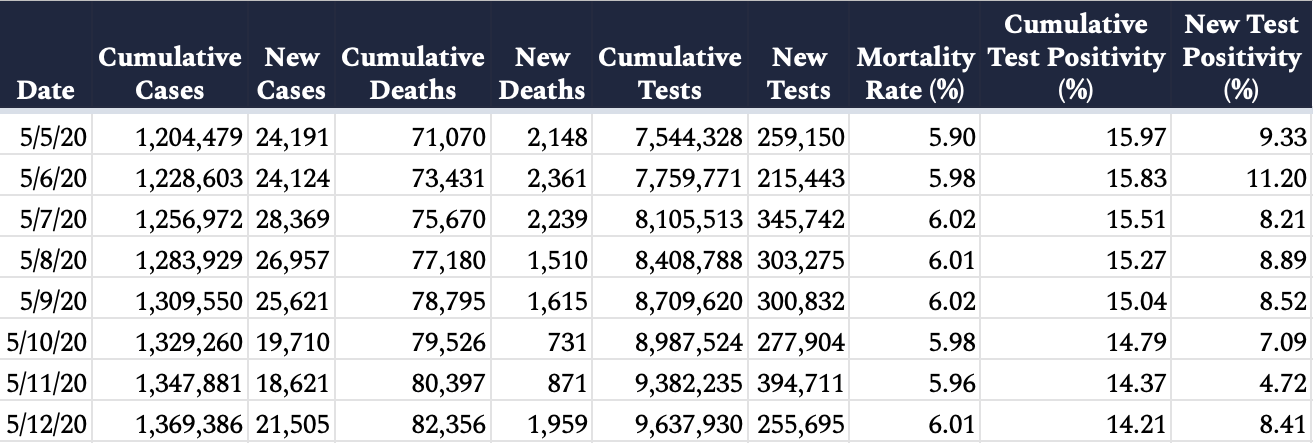

As of Tuesday night, there are now 1,369,386 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States (an increase of 21,505/1.6 percent from yesterday) and 82,356 deaths attributed to the virus (an increase of 1,959/2.4 percent from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 6 percent (the true mortality rate is likely lower, but it’s impossible to determine precisely due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 9,637,930 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States (255,695 conducted since yesterday), 14.2 percent have come back positive.

-

Dr. Anthony Fauci testified before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee on Tuesday, telling senators that a vaccine would likely not be ready “to facilitate reentry of students into the fall term,” but that “it is much more likely than not that we will get a vaccine” within the next year or two. He added that the virus’s death toll in the United States is “almost certainly” higher than the figures currently being reported, and argued there is a “real risk that you will trigger an outbreak” if states begin reopening too soon.

-

In the same hearing, coronavirus testing czar Adm. Brett Giroir told lawmakers he hopes the United States will be able to conduct 40 million to 50 million COVID-19 tests per month by September. Slightly fewer than 10 million tests have been conducted since the pandemic began.

-

The United States’ consumer-price index—a measure of economic inflation—declined 0.8 percent in April amid coronavirus lockdowns, the largest one-month drop since 2008.

-

Afghanistan has restarted its offensive against the Taliban after forces aligned with the terror organization killed 40 people—including two newborn babies. The region has seen a spike in Taliban attacks in the weeks since the United States signed an exit deal in late February.

-

House Democrats released their version of a $3 trillion phase four coronavirus relief package on Tuesday, that would send billions of dollars to state and local governments and hospitals, as well as extend the CARES Act’s $600/week* unemployment insurance boost from the end of July through the rest of 2020. Republican leadership and the White House have signaled a desire to wait and reassess the need for additional legislation.

Kids and COVID: When Can We Go Back to School?

Even as businesses begin to reopen across America, there’s another set of institutions that are months away from even thinking of going back to business as usual: our nation’s schools. Since we were already on the home stretch of the school year when lockdowns began, most parents and educators have long since reconciled themselves to bringing this one home via distance learning. But most have assumed—or at least hoped—that we’ll have enough of a handle on things by the end of the summer that schools will be able to resume relatively normal education operations come fall.

That could very well be the case—but it’s too early to say for sure yet, as was demonstrated by a terse exchange between Sen. Rand Paul and Dr. Anthony Fauci at a Senate hearing Tuesday morning. Paul, who is also a doctor and a COVID-19 survivor to boot, insisted that the fact that children are evidently less susceptible to the disease meant we should be on a path to reopen schools in most areas of the country.

“It’s not to say this isn’t deadly, but really, outside of New England, we’ve had a relatively benign course for this virus nationwide,” Paul said. “And I think the one-size-fits-all, that we’re going to have a national strategy and nobody is going to go to school, is kind of ridiculous. We really ought to be doing it school district by school district, and the power needs to be dispersed because people make wrong predictions.”

Fauci partially agreed—but cautioned that we don’t fully understand how the virus affects children yet, and that the nation was unlikely to have progressed enough in its response by fall to simply resume education as usual.

“The idea of having treatments available or a vaccine to facilitate reentry of students into fall term,” he said, “would be something that would be a bit of a bridge too far.”

Neither Paul nor Fauci was wrong on the facts. The truth is that, at this stage, we simply don’t know enough about how children and the virus interact to be able to start setting policy about what things will look like when the summer draws to a close.

The primary concern isn’t necessarily the children’s own health. It isn’t that kids are in no danger—as we discussed in yesterday’s Morning Dispatch, there have been concerning reports of serious inflammatory disease in some COVID-positive children. But it’s safe to say that risk of death via COVID is far lower to children than it is to pretty much any other population group.

The bigger issue is transmission. As any parent or educator could tell you, every school in America turns into a petri dish of infectious diseases when temperatures drop in the fall: Kids are highly social, questionably hygienic at best, and sit in close quarters in classrooms for hours and hours every weekday. The biggest public health concern isn’t that they’ll get seriously sick themselves—it’s that their parents, grandparents, teachers, and administrators might.

How much risk is there of that? Well, it’s hard to say: After all, we shut down schools very early in this process. Some scientists argue that the fact that COVID-infected kids are more likely present as asymptomatic lessens their ability to infect others: No coughing and sneezing means fewer pathogens hurled around the room. But there’s also some preliminary data to suggest that children grow a viral load that’s just as heavy as that of adults—and in confined spaces like a home, you don’t need to be hacking everywhere to get enough germs out there to risk contagion.

British pediatricians Alasdair Munro and Damian Roland summed the situation up in a paper last week: How infectious a child is once he has COVID “is almost impossible to tell at the moment, as we have no direct experiments comparing exposure to an infected child to exposure to an infected adult—in particular as children appear to make up a small number of index cases.”

The good news is that this lack of information is likely to be remedied as back-to-school dates draw closer. Many countries around the world don’t take as long a summer break as the U.S. does, and some countries that have made more progress controlling the virus are already beginning to reopen their schools.

“I imagine we’ll have more data before school reopenings to guide us as to which practices seem to help the most versus which ones didn’t provide too much incremental gain,” Dr. David Rubin told The Dispatch Tuesday. Rubin directs the PolicyLab research group at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and he has been working with schools and policymakers in the state to develop protocols for how to reopen safely in the fall.

“If you’re smart about the strategies you choose and you understand where your community is with regards to circulating cases and transmission, you can have—not an on/off switch, like we’re either in school or out of school, but a dimmer switch,” he said. “That at periods of low circulating cases and low transmission like you might have at the end of summer, it might be easy to have a range of activities that you’re doing in school, including sports, et cetera. But that when cases begin circulating, as you might expect later in the fall, you might have to pull back on that given that transmission risk in the higher levels of cases circulating across the community.”

One wrinkle in schools’ planning is that they’re already on vacation during the months when respiratory transmission of viruses tends to be at its least dangerous. It’s thus likely less a matter of whether many schools will be able to reopen in late August or early September than whether they’ll be able to stay open throughout the winter as seasonal bugs crop up again and the risk increases of a second wave of COVID cases.

“Some school districts, I feel, will probably try to open schools earlier and maybe plan for a longer winter break,” Rubin said, “as a way of already planning in the likelihood that we might need some distancing over the winter time if we lose control of the epidemic in some areas.”

But Rubin echoed Fauci in cautioning that maintaining open schools would require vigilance and prudence on the part of local officials and parents: a willingness from parents to continue practicing good virus-quashing behaviors and a willingness from administrators to be willing to pull back to remote practices for a while if local cases begin to creep up dangerously again.

“The types of things that parents are going to need is, what do I do when my kid gets home from school at the end of the day?” he said. “I expect we’re going to encourage them to do a lot to focus on hygiene and disinfection in their house. You know, if it were my kids, and I have kids as well too, they’re going right to the showers. We’re wiping down their books when they come in. And then I’m carefully monitoring for whether there are any symptoms that would require them to be a little more careful.”

‘Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!’*

There were no clear winners yesterday after the Supreme Court heard nearly three and a half hours of telephonic arguments about whether the president could be compelled to turn over his personal financial records.

The first argument involved subpoenas sent to banks to obtain Trump financial records sought by three different committees of the House of Representatives, implicating various separation-of-power concerns between two branches of the federal government. The second argument was about a grand jury subpoena for the same materials from the New York County District Attorney, which is conducting a criminal investigation into the Trump Organization under state authority.

Many of the justices asked the president’s attorneys to distinguish their arguments from a previous Supreme Court case involving a federal civil lawsuit brought by Paula Jones against President Bill Clinton. The unanimous opinion from 1997 held that “the Constitution does not automatically grant the President an immunity from civil lawsuits based upon his private conduct.” Of the justices who signed onto that holding, only Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer remain.

“The aura of this case is really sauce for the goose that serves the gander as well,” Justice Ginsburg said to Trump attorney Patrick Strawbridge. “So how do you distinguish, say, Whitewater, when President Clinton’s personal records were subpoenaed from his accountant, or even Hillary Clinton’s law firm billing records were subpoenaed? … Take the Nixon tapes?”

The same justices, however, were also concerned about the potential for harassment by political opponents. Justice Ginsburg, for example, asked general counsel for the House of Representatives Douglas Letter, “What is … the limiting principle … say legitimate legislative purpose looking toward enacting a law, but not to harass a president from the opposing party?”

There are a range of outcomes that the justices may consider in these cases, including a compromise position put forward by the advocates from the solicitor general’s office that the president should get “some measure of heightened protection” requiring Congress, for example, to show a specific legislative purpose. Although at times, the justices seemed skeptical of entangling themselves in just such an inquiry. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked, “why should we not defer to the House’s views about its own legislative purposes?”

Perhaps Chief Justice John Roberts put it best when he asked, “At the end of the day this is just another case where the courts are balancing the competing interests on either side.”

The court’s decision is expected in late June.

* These are the opening words before any argument before the Supreme Court as the justices customarily take their seats, and even by telephone, today was no different. As the Supreme Court Historical Society explains, “From the centuries that Anglo-Norman or ‘law French’ was the language of English courts, the word for ‘Hear ye!’ survives.”

Worth Your Time

-

Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson has spent her career trying to warn the GOP of its impending electoral crisis with young voters. But as she argues in her latest column, it’s senior voters that could doom President Trump’s re-election come November. “The challenge Trump is facing with seniors is very real, and the evidence is mounting,” she writes. “It did not start with the coronavirus crisis, but it has been made even more acute during this time, when nursing homes are overwhelmingly being hit hardest and poor handling of the public health situation can seriously endanger the lives of people whom Trump relies upon most at the ballot box.”

-

This post from immunologist and UMass-Dartmouth professor Dr. Erin Bromage is sobering, but an important read nonetheless. In layman’s terms, it breaks down the various ways you can contract the coronavirus, and outlines the most effective ways to avoid it. “If a person coughs or sneezes, those 200,000,000 viral particles go everywhere. Some virus hangs in the air, some falls into surfaces, most falls to the ground. So if you are face-to-face with a person, having a conversation, and that person sneezes or coughs straight at you, it’s pretty easy to see how it is possible to inhale 1,000 virus particles and become infected. But even if that cough or sneeze was not directed at you, some infected droplets—the smallest of small—can hang in the air for a few minutes, filling every corner of a modest sized room with infectious viral particles. All you have to do is enter that room within a few minutes of the cough/sneeze and take a few breaths and you have potentially received enough virus to establish an infection.”

Something Fun

Take that, coronavirus.

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

David’s latest French Press (🔒) takes a look at why we just can’t shake the 2016 election. “I cannot think of a single moment in my life when both major-party presidential candidates put such immense pressure on federal law enforcement in a time of extreme partisan polarization,” he writes.

-

Jonah had Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome on The Remnant to discuss a potpourri of topics. China hawkishness, dolphin propaganda, the Platonic Nacho—this podcast has it all. Tune in here.

-

Alec has a new Fact Check out, this one tackling claims that 60 Minutes deceptively edited an interview of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in which Pompeo said coronavirus was “manmade,” but quickly backtracked to claim the opposite.

-

On the site today, contributor Timothy Sandefur cautions against the idea of New Deal-style government programs to fight the economic hardships caused by the pandemic. “While Depression-era projects such as Hoover Dam are today viewed as triumphs of the age,” he writes, “less well-remembered are the countless thousands of workers assigned to such time-wasting tasks as studying ancient safety pins or stenciling fire hydrants in Brooklyn (at a cost of more than $100,000).”

Let Us Know

A new poll out yesterday found that 71 percent of Republicans believe the worst of the coronavirus outbreak is behind us, while 74 percent of Democrats believe the worst is yet to come.

Our question to you is a little more meta: Why do you think there’s such a massive partisan split in the response to this question?

Correction, May 13, 2020: An earlier version of this post mistakenly said the CARES Act implemented an additional $600 per month in unemployment benefits, rather than per week.

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Sarah Isgur (@whignewtons), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by Sebastian Kahnert/Picture Alliance/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.