The Snack

It’s Election Day in Georgia. There are plenty of reasons to think Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock will beat Republican Herschel Walker: the built in advantage that incumbents have, the slight lead Warnock had in last month’s election, the polls that show Warnock slightly ahead. On the other hand, GOP Gov. Brian Kemp won by 8 points so we know there’s more than enough votes for a Republican to win in Georgia.

And then there’s the early vote. The single-day numbers have broken records in Georgia, but that’s also what happens when you compress three weeks of early voting into one. For this runoff, 1.8 million Georgians have voted early. To give you some frame of reference, 2.5 million people in the state voted early ahead of the November election and 2.6 million voted early before the 2020 election. So while 1.8 million people is a lot of early voters and indicates high turnout for an off-cycle election and good news for Democrats, it also means we aren’t expecting anything like the numbers we saw in the last Georgia runoff, which determined control of the Senate. In fact, more people voted in those 2021 Senate runoffs—4.5 million—than voted in the 2022 midterm elections—3.9 million.

Regardless, I’ve harped on how Donald Trump fundamentally put Republicans at a disadvantage by discouraging their early vote turnout. But there was a specific event in Georgia worth mentioning because it had nothing to do with Trump. In short, Democrats filed a lawsuit to allow counties to decide for themselves whether to have early voting on the Saturday after Thanksgiving. The judge said they could, and the result was that several Democratic counties held early voting that day and a bunch of Republican counties didn’t. It looks like about 70,000 people voted on that Saturday, mostly in and around Atlanta. I doubt the election will come down to those votes, but it’s another example of Republicans cutting off their early voting nose to spite their election results face.

The Meal

Let’s talk about presidential primary polling. Let’s start with a quick rundown of where we are right now—just under two years out from Election Day 2024. FiveThirtyEight lists 33 Republican primary polls since Election Day. To start, the sheer volume of data is extraordinary. To get those same number of polls for the Democratic field after Election Day in 2018 would have taken you into February.

(Sidenote: the number of polls that go into the field in any given month is totally arbitrary. It’s decided by individual polling organizations and that in turn is based on their budgets and whether they think they’ll learn anything interesting. This was a bit of a “thing” in 2015 for me. Participation in the 2015 Republican primary debate main stage was determined based on a rolling polling average, but rolling averages don’t work when the inputs aren’t consistent. Example: Assume the debate is in September and the networks have agreed to average the last 10 polls. That works out well enough if there is one poll per week. But it doesn’t work if there were seven polls in July and only three in August. It’s especially galling if your candidate was outside the top 10 for all of July but crushed it at the kids table in the August debate and rocketed to No. 3. Anyway, that’s all to say that I pay a lot of attention to the effect of bunching in polling averages.)

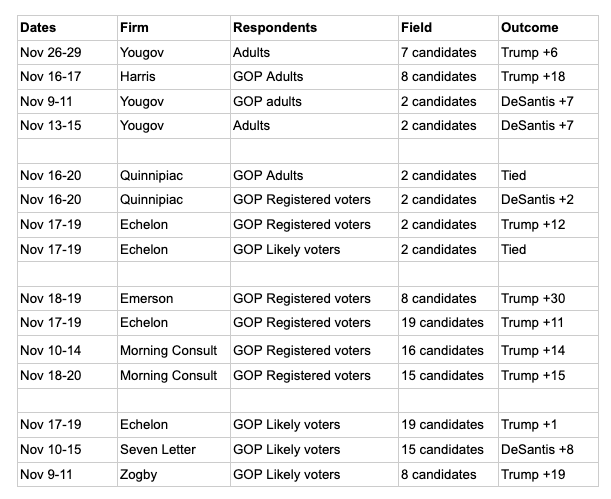

Back to our 33 polls. To figure out what any of these polls mean, we need to break them down along a bunch of different metrics—who was included, where the poll was conducted, and who was asked.

Let’s start with who was included in the question. Of the 33, 17 include only Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and Trump and 16 include other Republican candidates. Right off the bat, those are very different polls. The Trump vs. DeSantis polls are not realistically assessing how a primary works. So why conduct them at all?

First of all, it’s a lot cheaper to ask a simple head-to-head question because pollsters are limited by time. Every additional minute means someone will hang up and all of their answers are lost. Each additional name is like asking an additional question, which means the more Republican names the pollster includes for that question, the fewer overall questions they can ask in that poll. If you’re a polling firm, that’s a paying client’s question you’re cutting. If you’re a news organization, that’s a different headline that can’t be written. Either way, time is money.

The problem is, it makes the whole enterprise unrealistic. If we wanted polling on who is most likely to win if the Republican nominating contest were held today, we would need a poll in Iowa with all the potential candidates—only one of whom has actually announced, by the way—and then you’d put a poll in the field in New Hampshire to ask, “If you just learned that Donald Trump won the Iowa caucus and Ron DeSantis came in second and Glenn Youngkin came in third, who would you vote for in the New Hampshire primary?” And then change the order for all possible outcomes. And then do the same thing in South Carolina and Nevada.

Or to make it less egregious, just look at the Georgia results from last month. Almost all of the polls asked about Warnock vs. Walker. But that wasn’t really the right question to ask. Georgia requires every candidate to get more than 50 percent, and the actual election wasn’t just between two candidates. Libertarian Chase Oliver ended up with about 2 percent of the vote. If we wanted to know who the next senator from Georgia would be, we didn’t really want to know who midterm voters preferred between Walker and Warnock. We wanted to know whether any candidate could get above 50 percent when we included a third option.

But when it comes to presidential primary polling, the best data isn’t going to try to figure out who will win a nominating contest that is 13 months away. We want the vibes! We think the early, gut sense of Republican primary voters across the country will tell us something about the momentum and viability of these candidates way before we get anywhere close to a corn field. And that’s why I think both sets of polls are worth something in this case.

Just at this very top level, we would assume that Trump would lead the pack in the large field polls and DeSantis would do better in the head-to-head polls. Indeed, Trump leads in nine of the 13 large-field polls in which he was included—by as many as 30 points and by as little as 1 point. DeSantis leads Trump in the other four. (In the other three polls without Trump, DeSantis is 30-plus points ahead of anyone else.)

But these polls aren’t apples to apples—not even close. Obviously, they don’t all include the same field of candidates since there are a zillion people who might run and a bunch who won’t. One included both Trump and Donald Trump Jr. in the same poll—an unlikely scenario. Some included eight names; some included 19 options.

But there are even bigger problems when trying to compare them: where the polls were. Not all of these polls were national. For example, in one of those large-field polls, DeSantis is leading Trump, Liz Cheney, Ted Cruz, Mike Pence, and Nikki Haley in … Utah. Same thing happens in Texas. And in Iowa. In fact, DeSantis leads Trump in only one national poll when other candidates are included. (More on that poll later but hint: It’s about who they asked.)

Now for the head-to-head polls. DeSantis is winning in 13 and Trump is winning only in two. (Two were a tie.) But a lot of these were state polls as well (some more than one): Pennsylvania, Florida, Georgia, New Hampshire, Iowa. DeSantis won them all. Take out all of those, DeSantis is winning in five national polls against Trump, Trump beats DeSantis in two, and two are a tie.

Finally, we have to look at who was polled. The 33 polls aren’t polling the same types of people—all adults, adults who lean Republican, registered GOP voters, likely voters. On the one hand, trying to figure out who the likely voters are before we even know who the candidates are or what issues may emerge is pretty difficult. On the other hand, asking random American adults of all political stripes “who would you most prefer to be the Republican nominee for president in 2024” isn’t telling us much of anything about where Republican primary voters are.

So how can we actually learn from all this jumbled data? The most interesting numbers for me came from the same polls. Echelon Insights, for example, is included four times in this data set even though it’s all from the same sample. By doing it this way, we are able to compare the difference in a Trump vs. DeSantis matchup with registered voters and likely voters and a larger GOP field question between those two groups as well—and all within the same time period and with the same methodology. Quinnipiac and Marquette had the same idea, comparing all adults to registered voters in their poll with just a head-to-head question.

Among registered voters, using the Echelon data, Trump led DeSantis by 12 points in the head-to-head and 11 points in the larger field. But narrow the respondents to likely voters, and Trump and DeSantis are tied in the head-to-head and Trump leads by 1 point with the larger field. The same trend happens in the Quinnipiac head-to-head poll. Among all adults, Trump and DeSantis are tied—but when we narrow it down to registered voters, DeSantis pulls ahead by 2 points. Ditto Marquette. In the Marquette head-to-head poll, DeSantis’ lead increased by 5 points when they narrowed the respondents from all adults to registered voters.

The point is that the 33 polls are all over the place because they aren’t asking the same thing or asking the same people. But the obvious trend is that DeSantis is doing better right now with people who are paying the most attention. That’s good news for DeSantis because that’s a good description—not only of Republican primary voters—but also of how primaries play out: A relatively narrow sliver of highly engaged, grass-tips——as opposed to grassroots–leaders within a political party can shift focus onto one candidate in a big field like a single starling in a murmuration.

Or to put a more fine point on it: As we’d expect, Trump is still leading by double digits in all of the national polls when it’s a large field—even among registered voters (Morning Consult, Emerson College, and Harris).

But in the few national large-field polls where pollsters looked only at likely voters, suddenly it’s a much tighter race. DeSantis is ahead in one, statistically tied in one, and behind in one (Echelon, Seven Letter, and Zogby, respectively.) And I’d argue this is more representative of who will influence the GOP primaries.

And we also haven’t talked about trends within the same polling company. The Harris poll shows Trump leading DeSantis in a big field by 18 points. But Trump has dropped 9 points and DeSantis has shot up 11 points since the last time they conducted the poll. That’s obviously meaningful regardless of who is up or down this far out.

Here’s a chart of 14 of the national polls mentioned above, focusing on the differences between large field and head-to-head outcomes and who was being asked.

The Dessert

Don’t forget to look for the silver lining this week.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.