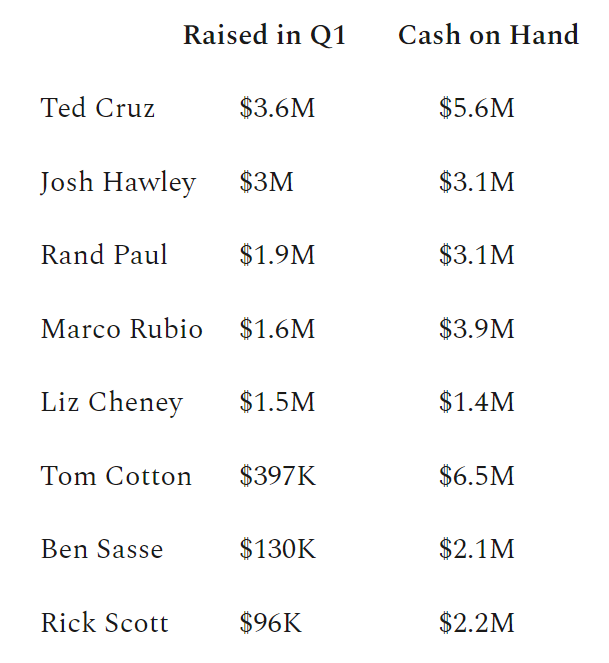

Campaign Quick Hits

We’ve got the FEC numbers for candidates raising “hard dollars” between January 1 and March 31. Hard dollars refers to money that is raised under the federal contribution limits, and it means we’re only looking at federal officeholders at this point. Even so, you start to see the vague shape of a 2024 race and what types of candidates GOP donors are putting their money behind. (Spoiler Alert: They still like Trump!)

To me, the most interesting number up there is the Liz Cheney one. Yep, she raised a lot. But she ended the quarter with less money than she raised. Why? Either she had to spend a lot to raise that amount, or she is already spending real money even though the primary isn’t until August of next year. More likely the answer is both, and that’s even worse. She’ll win her seat again, I predict, but it’s hard to miss what it says about the direction of the party.

Of Candidate Recruitment and Reverse Coattails

We’ve discussed congressional candidate recruitment in this newsletter before. The process is often a dance between party leaders (both local and national) and wannabe candidates. The candidate seeks to prove her prowess at wooing donors and local party activists. Party leadership works to convince her that the race is worth her time and that she can win. But what if she can’t? What happens in districts that are for all intents and purposes unwinnable?

In the past, party leadership didn’t spend much time in those districts, so they didn’t really care who ran under the party’s banner as long as it wasn’t someone who embarrassed the party’s brand nationally. Some districts wouldn’t recruit anyone at all.

But I predict the national parties are about to create a new office: The Director of Losing Candidate Recruitment.

A progressive organization called Run for Something released a study this week showing that Joe Biden “performed 0.3 percent to 1.5 percent better last year in conservative state legislative districts where Democrats put forward challengers than in districts where Republicans ran unopposed.”

The traditional thinking is that low-propensity voters turn out to vote for a presidential candidate and then haphazardly vote for some lower ballot candidates while they are there. But in this case, Biden’s coattails didn’t help those lower-ballot candidates in deep red areas. Lower ballot candidates flipped the script and increased Democratic turnout in those unwinnable precincts, boosting Biden’s overall statewide numbers.

Bear in mind that studies have shown that “showing someone 100 ads in the month before the election in a presidential race increases their odds of voting for you by 1 percent” and door knocking within two months of election might help a candidate to the tune of 1.5 percent. And we know campaigns are willing to spend hundreds of millions on ads and field organizing. So a 1.5 percent effect just for convincing someone to lose a state house race? Huge.

Of course, as always, there are some caveats here. First, this study was done on state house races. It’s unclear whether the effect would be larger or smaller at the congressional level. Every cycle, one side or both says they are pursuing a “50-state strategy,” and they never are. Budgets are built in advance and, not surprisingly, the majority goes to advertising in top-tier races, with not much left for putting full-time organizing staff in losing races. Entrenched interests of incumbents in tighter races, political consultants who make their living this way, and party leaders who get elected on their win-loss record, are, well, entrenched.

Second, it’s not clear that top-down leadership could amplify the effect all that much even if they did put the resources there. The reverse coattails happened because, as the Run for Something co-founder said, “these candidates are supercharged organizers … they are folks in their community having one-on-one conversations with voters in ways that statewide campaigns can’t do.” Recruiting candidates, then, might not do any good. The losing candidates who ended up helping Biden were internally motivated to run for their own reasons, and their enthusiasm might not be replicable if the party has to cajole and persuade a less motivated candidate to run an unwinnable race.

Still, on the margins, there are surely people out there who would be more interested in running if they a) knew the party was behind them and grateful for their efforts and b) knew that their efforts would get their chosen Senate or presidential candidate into office even if they themselves wouldn’t win. All in all, here at The Sweep, we’re for more people running. (And you never know: Sometimes, the dark horse “never even observed in the list, rushe[s] past the grandstand in sweeping triumph!”)

I was all set to play rock paper scissors over who got to tell y’all about the Cook Political Report’s latest Partisan Voter Index score. I always go with rock, because I really like rocks. In fact, one of the biggest meltdowns I remember having as a child was over a rock—a purple geode that my dad didn’t even consider buying me. After his death, my uncle Nathan (the brisket’s namesake) left it to me in his will. Which is all to say, I was feeling very good about my rock pick. But then Chris just asked me nicely if he could do it and before I could break his scissors (we all know he would pick scissors), I found myself wanting to know what Chris thought about the score as well. So here you go!

Finally, More Swing Districts

If you’re a politics nerd (hey, you’re the one who signed up for this newsletter) you probably already know that the Cook Political Report has released its new Partisan Voter Index numbers by congressional district—the universal code for the political leanings of all 435 House districts. But on the off chance that you had better things to do over the weekend than toggle through dozens of maps, here’s a rough and ready guide.

After every presidential election and congressional redistricting since 1997, the crew at Cook, now led by the indispensable Dave Wasserman, averages each district’s performance in the previous two presidential elections as compared to the nation as a whole. Take Texas’ 2nd Congressional District in the north Houston suburbs, represented by Republican Rep. Dan Crenshaw. In 2016, Donald Trump underperformed prior GOP nominees in the district but still crushed Hillary Clinton. The district was then 11 points more Republican than the nation, or a Partisan Voter Index of R+11. But Trump collapsed there in 2020, winning the district by just 1.3 points. Voila: The new PVI is R+4.

If you’re wondering, the most Democratic district in the land is Pennsylvania’s 3rd, which includes West Philadelphia. It clocks in at D+41. The most Republican is Alabama’s 4th, a rural swath of the northern part of the Yellowhammer State: R+34. The median district is Virginia’s 2nd, which covers Norfolk and the Tidewater. When candidates, PACs and parties look for opportunities or threats, the PVI makes a useful guide. Republicans will be gunning hard for the seven Democrats representing districts with R+ numbers; vice versa for the nine Republicans in D+ districts. Rep. Jared Golden of Maine is the Democrat representing the reddest district (R+6) and Rep. David Valadao of California is the Republican in the bluest district (D+5). Generally, those between D+5 and R+5 are considered potential swing seats.

Now, I told you all that so I could tell you this: For the first time since the introduction of the scale 24 years ago, the number of these swing seats actually increased after a long slide. In 1997, there were 164 seats between R+5 and D+5. By 2005, the number had fallen to 108. By 2017, it hit rock bottom: Just 72 seats were considered competitive. In 20 years, the House went from having 38 percent of members in swing districts to just 17 percent. Indeed, we can explain much of how awful the House has become through this phenomenon. Members in safe districts tend to be less interested in accomplishments of broad appeal and more interested in preventing a primary loss to a challenger.

Before we go any further, let me answer the question many of you are already scoffed at your screen: This is not about gerrymandering. Wasserman points to the example of West Virginia’s sprawling 2nd District, which runs from the Ohio River to the D.C. suburbs. It was dead even in 1997 and is now R+20. The map didn’t change, but the voters did. This is all part of the great sorting of the past decades, in which voters increasingly related to politics as a national team sport instead of a local matter and aligned themselves utterly with the red team or the blue team. Here’s Wasserman: “Of the net 86 ‘swing seats’ that have vanished since 1997, 81 percent of the decline has resulted from areas trending redder or bluer from election to election, while only 19 percent of the decline has resulted from changes to district boundaries.”

That’s what makes this year’s first-ever increase in the number of competitive districts such a big deal, even at a scant six seats. If you want a Congress that isn’t just a perpetual outrage machine mostly devoted to holding pointless hearings to generate clickbait, you want more members of both parties worried about general election losses. I readily stipulate that this little bump may just be part of the country’s Trump hangover. It may be that districts like Crenshaw’s in Texas will swing back bright red if Republicans can find a less polarizing candidate in 2024. That may hold true in suburban districts from New Jersey to California.

But it may also be that one of the fruits of the nation’s ongoing political realignment is less certitude for members in both parties. That would be a healthy fear, indeed. Certainly Democrats from swing districts haven’t been shy about pushing back against the extremism from their colleagues in lopsided districts. Even Republicans are starting to show some signs of life. Even if it’s just a blip, I’ll take it.

2022 primary season is still a few months away from getting in full swing, but the country is already dotted with candidates taking the plunge early for one reason or another. Here’s Andrew with a very early look at what’s going down in the Show-Me State.

And Now, Missouri Republicans

Last week’s Sweep spent some time ruminating on the strategic factors candidates consider when deciding how early or late to jump into a race. This week, we wanted to take a look at how that dynamic is playing out in one of the early primary cycle’s stranger races: the contest to replace retiring GOP Sen. Roy Blunt in Missouri.

As is often the case in open-seat races, all sorts of people are reportedly gearing up to throw their hats in the ring, including U.S. Reps. Ann Wagner, Vicky Hartzler, Jason Smith, and Billy Long. More than a year out from the primary, however, these candidates are still biding their time. For now, the GOP field thus remains a two-man race between state attorney general Eric Schmitt and former governor Eric Greitens.

As we discussed last week, candidates who jump in extremely early run the risk of peaking too soon, so there’s often specific motives behind the earliest candidates to jump. Schmitt is a strong fundraiser with solid statewide connections whose primary task is boosting his name ID with primary voters, so it makes sense he’d want to get a running start. Greitens, meanwhile, has made the same move for nearly opposite reasons: Missourians already know him very well, and he’s trying to overhaul his image before a bunch of other candidates show up to start bludgeoning him.

Greitens, if you don’t remember, flamed out of Missouri government three years ago under fire from a number of scandals, most prominently one involving an extramarital affair and accusations of sexual blackmail and abuse. (Here’s our piece from earlier this month if you want a full refresher.) The facts of the scandal looked bad for Greitens; investigators from the state legislature—run by a supermajority of his own party—deemed the accusations credible. With impeachment looking likely, he resigned in mid-2018.

By getting in early, Greitens has given himself an opportunity to try to take control of his own story—in this case, by insisting the whole thing was a discredited witch hunt on the part of shady left-wing operatives trying to get him just like they tried to get Donald Trump. To put it mildly, it’s a stretch—Greitens, for instance, routinely pretends that a Missouri panel’s finding of no personal wrongdoing in an unrelated campaign-finance matter amounts to total exoneration across all his scandals. But he’s got a better chance of selling his argument to voters now than he would if they were just hearing it for the first time six months from now, with other candidates poking holes in it in real time.

Greitens’ other major problem is a lack of enthusiasm among “grasstops” activists—highly engaged grassroots organizers in the state who supported him enthusiastically during his governor’s race but felt burned by what came after. (“None of those people are involved in this campaign,” former state senator and Greitens ally John Lamping told The Dispatch earlier this month. “This is entirely coming from D.C. … There’s nobody in Missouri, like nobody.”)

It’s an unusual problem to have (few politicians attempt to deep-six apparent career-ending scandals this quickly), and Greitens seems to be approaching it with an unorthodox strategy. Rather than starting by building a meaty state operation and using that to expand both downwards and upwards—wooing state activists who then pound the pavement to spread the word to voters and using state fundraising success to try to convince national investors to hop in too—he’s simply starting at both extremes. Since he’s not currently in office, he has ample time to flood the zone with public appearances, taking his undeniable stump-speech gifts to as many individual voters around the state as he can—particularly the rural ones who were the most likely to remain loyal to him throughout his former downfall.

“What Eric did do in his last race is that he did commit to doing a lot of these small community places … that two of the other candidates did not do to the same degree, just because they had busier lives,” Lamping said this week. “So that is the thing that Eric can do, is he can just say, screw it, every time I get the chance to go to a Macon County, I’m going. Because he knows when he gets there, he’ll be well-received.”

At the same time, he’s bet heavily on the benefits of building a national brand—using contacts with Trump allies like Rudy Giuliani and Steve Bannon in an attempt to make his candidacy one of the Trump movement’s major causes going into 2022. This week, Kimberly Guilfoyle, former finance chair of President Trump’s campaign and the girlfriend of Donald Trump, Jr., announced she was joining the Greitens campaign as “National Chair.”

“I mean, he’s doing it backwards,” said veteran GOP consultant David Kochel. “The first thing you do to try to attract the attention of the national committees and national donors and all that is you build a strong organization in the state of activists, influencers, operatives, consultants, whatever, that help [people] kind of say, ‘Oh, he’s serious—he’s got these 50 Chamber [of Commerce] leaders, he’s got the heads of the three biggest gun groups in Missouri, whatever.’ And that sort of credentials you to the national observers. He’s obviously trying it the other way, which is, since he’s been able to convince Kimberly Guilfoyle to come on board, he hopes that actually attracts the attention of … Trump fans and Trump defenders in Missouri.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.