Welcome back to Techne! Last week, while browsing Reddit, I came upon a picture of a heavy press, which led me to learn about the tech. This video from the Machine Thinking YouTube channel explains the Cold War-era Heavy Press Program, which produced the 50,000-ton press that is key for aircraft manufacturing.

Some other odds and ends: a CIA report on Soviet metal forming from 1932 to 1956 and a feasibility report for making an 80,000- to 200,000-ton press.

Notes and Quotes

- U.S. officials are privately warning telecommunications companies that undersea internet cables crossing the Pacific Ocean could be at risk of tampering by Chinese repair ships. Specifically, State Department officials have raised concerns about a state-controlled Chinese company called S.B. Submarine Systems appearing to conceal the locations of its vessels from tracking services, suggesting potentially nefarious motives.

- In collaboration with the Biden administration’s national cybersecurity strategy, the Commerce Department has begun implementing new internet routing security measures called Route Origin Authorizations (ROAs) to defend against nation-state hackers and other malicious cyberattacks. ROAs cryptographically certify the legitimacy of websites and validate web traffic, helping to increase the adoption of secure internet routing technologies.

- Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft continues to face setbacks, with its launch being pushed back again to May 25 due to a helium leak in the service module. The spacecraft’s first crewed launch was scrapped last year, and its previously rescheduled May 6 launch was called off because of a faulty oxygen relief valve.

- House Republicans unveiled their long-awaited draft of the $1.5 trillion Farm Bill last Friday, but several provisions—related to nutrition programs, climate initiatives, and farm safety net funding—have proven divisive. The Farm Bill is an omnibus, multi-year law that governs agricultural and food programs and is typically renewed every five years. The current authorization ends September 30. This Congressional Research Service report is a good primer on the current politics of the legislation.

- Researchers at the National Energy Technology Laboratory in Pittsburgh found a large lithium deposit in the Marcellus Shale deposit stretching across Pennsylvania. Lithium is an important component of electric vehicle batteries, and the news comes a few months after researchers discovered a massive lithium deposit in an ancient supervolcano near the border of Nevada and Oregon.

- Benjamin Reinhardt published a new paper for Works in Progress—which he also summarized on Twitter—unpacking the material manufacturing process. Scaling up materials that work in the lab into commercial production is an uncertain process, but Reinhardt offers some pathways to overcoming these bottlenecks and building a pilot plant.

- ICYMI: I wrote a piece last week on the data in the Annual Capital Expenditures Survey (ACES) for robotic equipment and the Business Trends and Outlook Survey (BTOS) AI supplement. What’s striking among these two datasets is that industries buying robotic equipment differ from the industries using AI-like machine learning, natural language processing, and virtual agents. Manufacturing and retail trade spent the most on robotic equipment, but they tend to use AI the least. Automation is not just one thing.

- From Alfred Ng in Politico: “With little action in Congress, the burden of regulating tech has shifted to the states. And that pits state lawmakers, often with small staffs and part-time jobs, against powerful national lobbies with business and political clout.”

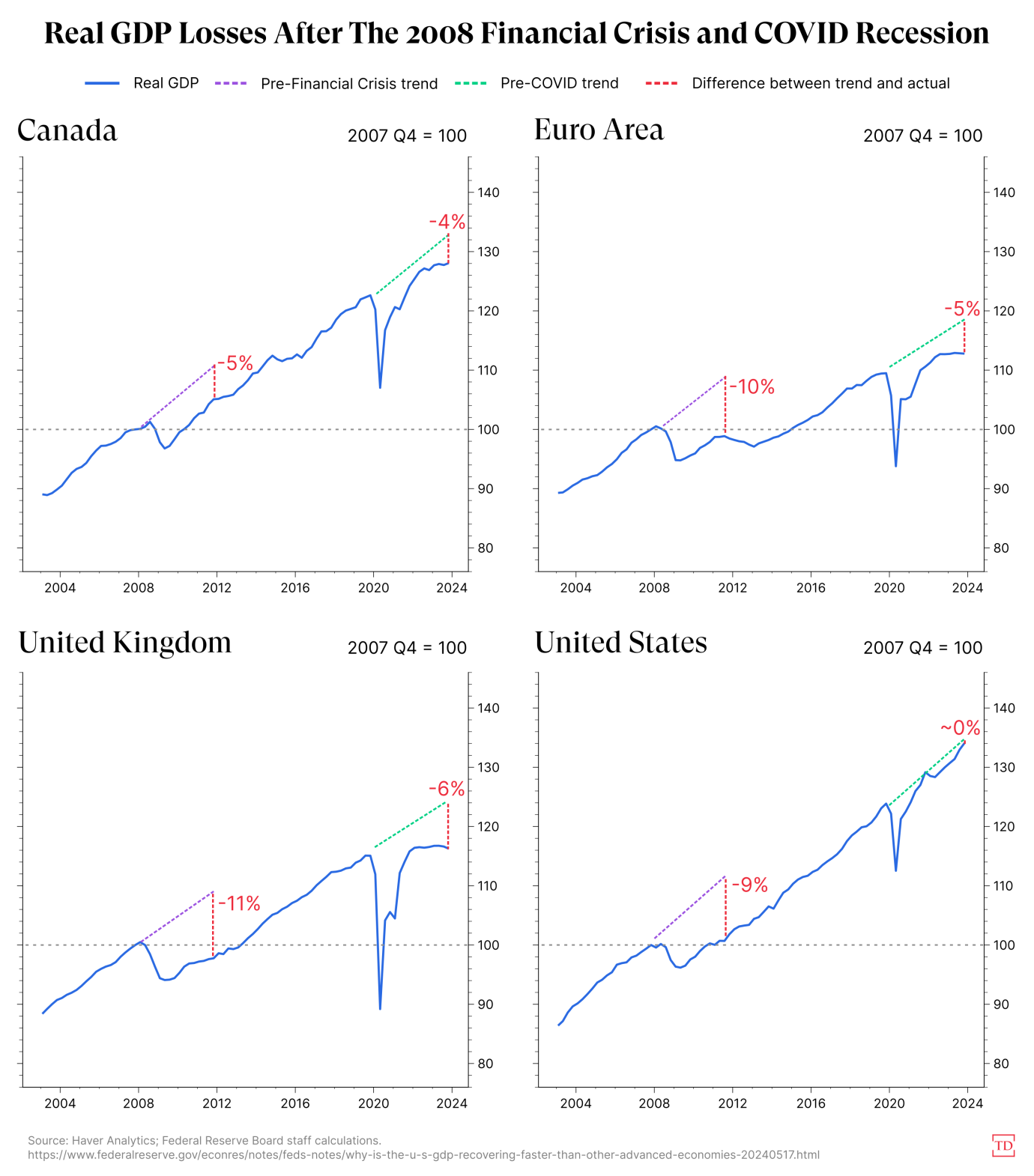

- America the weird: The U.S. is recovering from COVID-19 much faster than our peers:

Cambridge Analytica, a Redux

I recently listened to Jacob Siegel’s interview on The Fifth Column podcast and couldn’t help but reflect on the power of stories. I now recognize, some six years later, that the Cambridge Analytica scandal galvanized me—but not like it did so many others. For many, the story concretized the power of political advertising and targeted data, essentially kicking off what would become known as the “Techlash.” But even well-informed people got the story wrong, largely because they misunderstood the political ad industry and the influence of tech.

To quickly review: In March 2018, the New York Times published a story titled “How Trump Consultants Exploited the Facebook Data of Millions.” The report detailed how Christopher Wylie and the firm he helped found, Cambridge Analytica, was involved in deploying an “arsenal of weapons” in the culture war that helped Trump win the 2016 election. Cambridge Analytica was built on the work of Aleksandr Kogan, an academic at Cambridge University. Through an app he developed, Kogan collected Facebook profile data—in violation of the platform’s terms of service—and Cambridge Analytica used that data to develop psychographic profiles on individual voters, allowing it to sell a targeted political messaging service based on preferences, beliefs, and other cognitive characteristics. It was this hyperpersonalized messaging product that “underpinned its work on President Trump’s campaign in 2016.” Soon after the New York Times report, a secretly recorded video captured Cambridge Analytica’s CEO claiming his company “played a decisive role in U.S. President Donald Trump’s 2016 election victory.”

Data politics immediately skyrocketed to the top of the political discourse. Within weeks, Mark Zuckerberg was hauled in before Congress for questioning. He wouldn’t be the last.

The Cambridge Analytica news spurred California legislators into action. By June, they had passed the California Consumer Privacy Act, the country’s first comprehensive state privacy bill. The legislation directly mentioned Cambridge Analytica as the precipitating event for its passage. “In March 2018, it came to light that tens of millions of people had their personal data misused by a data mining firm called Cambridge Analytica,” the bill reads. “A series of congressional hearings highlighted that our personal information may be vulnerable to misuse when shared on the Internet. As a result, our desire for privacy controls and transparency in data practices is heightened.”

Nirit Weiss-Blatt, a communication researcher, also laid the “Techlash” at the feet of Cambridge Analytica in her 2022 book, The Techlash and Tech Crisis Communication. After the news became public, trust in big tech companies dropped. Jia Tolentino was right when she said in 2019 that we “live in the world that Cambridge Analytica wrought.”

Still, I was far too familiar with Cambridge Analytica and the industry in which it operated to be convinced of the insinuation. I knew people who worked in political advertising, and they’d been talking about the technical problems with Cambridge Analytica’s data for years at that point. AdAge had even run a report on the company in the middle of the 2016 election season. The firm’s unreliable data was no big secret.

So when the news broke in 2018, I wrote a Medium post and asked, “Did the company really have some secret sauce that it unleashed upon the 2016 electorate?” My response: “From almost every serious person I know in this business, the answer is no.” Some important context was missing, I argued:

Throughout the summer [of 2015], wealthy donors and leaders within the Republican party were calling for the RNC to stay out of the election and that put the Trump team in a bind. The Trump campaign had tested the RNC data, and found it [to] be far more accurate than what Cambridge Analytica had to offer. But Cambridge Analytica was a hedge in case the RNC wouldn’t share its data. So when an agreement was reached between the RNC and the Trump campaign, they dumped CA.

From the people I have talked to, CA data was known to be costly and unproven, which put it at a disadvantage in the competitive landscape of political data.

About a year after I wrote that piece, the New York Times seemed to confirm my hunches:

But a dozen Republican consultants and former Trump campaign aides, along with current and former Cambridge employees, say the company’s ability to exploit personality profiles—“our secret sauce,” Mr. Nix once called it—is exaggerated.

Cambridge executives now concede that the company never used psychographics in the Trump campaign. The technology—prominently featured in the firm’s sales materials and in media reports that cast Cambridge as a master of the dark campaign arts—remains unproved, according to former employees and Republicans familiar with the firm’s work.

We now know that Cambridge Analytica was vaporware: It didn’t deliver on its lofty promises. Aleksandr Kogan, who had kept quiet under advice from his attorney, would later say that the data profiles were never good. Both Brad Parscale, the 2016 Trump campaign’s digital director, and Matt Oczkowski, Cambridge Analytica’s erstwhile chief product officer, have since reiterated that they didn’t use psychographic targeting during the 2016 campaign.

Besides, Trump’s election team was focused all along on securing the big voter file that the Republican National Committee (RNC) has maintained, typically called the Voter Vault. That deal was signed in December 2015, when it became clear that Trump was a legitimate contender for the party’s presidential nomination. The voter file, which includes decades of voting patterns, is always the preferred data backbone. Cambridge Analytica’s data simply cannot compete. “The RNC was the voter file of record for the campaign, but we were the intelligence on top of the voter file,” Oczkowski said later. “Sometimes the sales pitch can be a bit inflated, and I think people can misconstrue that.”

The Rhetoric of Cambridge Analytica

Had you been following the story as closely as I was, the Cambridge Analytica revelations would have also struck you as cutting against many of the commentariat’s worries from before the election. With Hillary Clinton poised to become the next president—the New York Times’ Upshot vertical gave her an 85 percent chance to win—a number of people were more concerned that Facebook, given its left-leaning employee base, might instead scrub its News Feed of Trump stories, zapping the campaign of its power.

So when election night 2016 came to a close, many—including Trump himself—were stunned. And in March 2018, the Cambridge Analytica story conveniently emerged to explain—in the form of a Greek tragedy—what had transpired two years earlier.

For the Greeks, tragedy was not just a misery memoir but the foil to comedy, the theater of grotesque and absurd. Orestia, for example, does not end unhappily. Rather, tragedy is the form through which a morality tale can be told. When Aristotle talks about tragedy in Poetics, he is really talking about serious drama or an important story. That’s why he defines tragedy as a tale that is serious or important, is acted out, and comes to a satisfying conclusion, thereby purifying the tragic act itself.

Poetics also highlights two moments that drive the tragedy: the peripeteia and the anagnorisis. The peripeteia, in Aristotle’s words, is a shift in the story, “a change by which the action veers round to its opposite, subject always to our rule of probability or necessity.” Often, however, the main character doesn’t realize things have changed—until the anagnorisis, or discovery: “a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune.” The peripeteia is the turn of fortune, while the anagnorisis is the realization of it.

The Cambridge Analytica saga captured the popular imagination because it completed a Greek tragedy of sorts. The 2016 election represented the turn of fortune, or peripeteia. Two years later came Cambridge Analytica, the moment of critical discovery, a sudden awareness of things as they truly stood—the anagnorisis.

Purifying the Act

In a world of information, disinformation is a transgressive act. The transgression of Cambridge Analytica and its discovery later turned the 2016 election into a Greek tragedy. American democratic norms have long been built on the rational, informed citizen. As I have explained elsewhere, political scientist Michael Schudson’s The Good Citizen documents the centuries-long transformation of our expectations of citizenship:

[Schudson] takes on the idealized “informed citizen,” which, as he rightly points out, was not an expectation in eighteenth-century political circles. Rather, it took hold in the later part of the nineteenth century as education began to spread, and objectivity became a pillar of newspapers, finally becoming the yardstick it is today when the Progressives coupled both with public education and civic participation.

Informed citizens put into place elected officials who are then expected to translate constituent preferences into public policy. Then, through the media, citizens are duty-bound to keep informed of their representatives so that, when agendas no longer align, that person is replaced. In its disruption of said rationality, disinformation becomes the deadliest of the technological sins: a sin against the polity.

So when Jacob Siegel was on The Fifth Column podcast earlier this month to discuss his upcoming book, I couldn’t help but think of the purifying act of the tragedy and my theory of Cambridge Analytica as a story. The book—which expands on his 2023 Tablet article, “A Guide to Understanding the Hoax of the Century”—is about the “parallel federal government” of “nonprofits and the academic media” that emerged in the wake of Cambridge Analytica. The evidence is now clear that various federal agencies—including the FBI, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and even the White House—were using nonprofits as a passthrough to convince Twitter to restrict speech in the name of disinformation. There’s even a pending Supreme Court case about its legality.

I’m excited to read the book because Siegel is one of the few journalists who is approaching this problem with the right mindset. “American voters aren’t that stupid,” he said. “They aren’t that gullible. Yes, the internet is a powerful tool, but there’s not some hyper-efficient mechanism of causality where, if you put the right meme into circulation on Twitter, people vote for the candidate you want them to vote [for].” Only with that kind of outlook can you really understand the information ecosystem after Cambridge Analytica.

Until next week,

🚀 Will

AI Roundup

- The bipartisan Senate AI Working Group—led by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Sens. Mike Rounds, Todd Young, and Martin Heinrich—released an AI roadmap last week, outlining a vision of AI policy built on eight detailed sections, including enhanced investment, workforce reskilling, and transparency. In response, a group of advocates released a shadow report explaining where the roadmap misfires.

- Multistate, a government relations firm, recently updated its state-by-state AI policy overviews and legislation tracker. More than 700 bills aimed at regulating AI are now pending in the states.

- Colorado has become the first state to enact a law regulating artificial intelligence systems. The new regulation, signed into law on Friday by Democratic Gov. Jared Polis, requires developers of “high-risk” AI systems to take reasonable measures to avoid algorithmic discrimination. It also mandates that developers disclose information about these systems to regulators and the public, as well as conduct impact assessments.

- The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has launched an investigation into the safety of Waymo’s self-driving vehicles following 22 crashes involving the company’s cars since 2021. The four most recent incidents cited in NHTSA’s notice include two collisions with parking lot gate arms, a collision with a small object, and clipping a parked car.

- The co-founder of Hugging Face, a firm that builds AI tools, released a reading list for those interested in understanding AI.

Research and Reports

- Researchers at Apollo Research, which specializes in AI application, demonstrated that Large Language Models “trained to be helpful, harmless, and honest, can display misaligned behavior and strategically deceive their users about this behavior without being instructed to do so.”

- I’m looking forward to reading Andrew K. Przybylski’s newest paper—which he co-authored with Matti Vuorre—on whether or not internet use is bad for you. Nature covered the paper, which is a 16-year study of 2.4 million people that concludes “internet access and use predict well-being positively and independently from a set of plausible alternatives.”