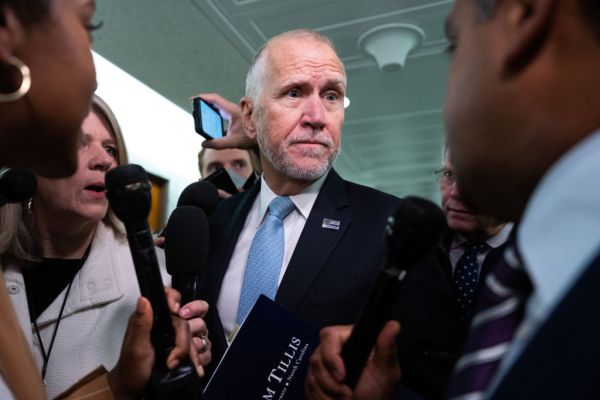

The man most likely to become House speaker next year has been signaling plans for the upcoming Congress, and his comments have set Democrats and even some Republicans on edge. House GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy’s musings on the debt ceiling and the future of aid to Ukraine could lead to an interesting lame-duck session—but it’s complicated.

Let’s start with Ukraine.

Ambiguity Is the Point

America has authorized more than $60 billion in aid to Ukraine since the war began earlier this year. When McCarthy suggested this week that a Republican House may not be willing to offer more, he left a lot of wiggle room. And his office isn’t offering clarity on what, exactly, he meant.

The ambiguity is probably intentional: Republicans on the whole haven’t quite determined whether they will go along with the conventional foreign-policy wing of the party and continue to support Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s invasion. The anti-interventionist, Donald Trump-backed sect of the GOP that doesn’t want to spend money on a war in Europe could still win out. If Republicans take one or both chambers of Congress next month, they might ultimately meet in the middle.

“I think people are going to be sitting in a recession and they’re not going to write a blank check to Ukraine,” McCarthy told Punchbowl News in an interview published this week. “They just won’t do it.” He criticized the Biden administration’s domestic policies, particularly on the southern border, and added, “Ukraine is important, but at the same time it can’t be the only thing they do and it can’t be a blank check.”

You may notice from his repetition that the operative words here are “blank check.”

Do his comments mean future spending on Ukraine could have Republican support in the House, so long as it includes robust oversight provisions? That’s what the top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee theorized afterward. The idea doesn’t come out of nowhere: Republicans like Sen. Rand Paul have pushed for more accountability over how the money is spent.

Or was McCarthy airing skepticism about the prospects for any Ukraine aid? How far do GOP questions about it go? Rep. Chip Roy, a Texas Republican and member of the conservative House Freedom Caucus, suggested the conference will be looking beyond oversight concerns.

“How much more? Have we replenished our assets? Are we paying for it? Is more support in our interests? Are we changing energy policies?” Roy wrote Tuesday.

McCarthy’s office didn’t respond to The Dispatch’s requests for comment on what he meant by “blank check,” nor did it answer the same question from my former colleague John McCormack.

Set aside how irresponsible it is for a party leader not to clarify comments of this magnitude. It’s striking how closely McCarthy’s words aligned with what House Freedom Caucus Chairman Scott Perry told me in September when asked about Ukraine aid. Both highlighted accountability as a priority, pointed to the border, and declined to make any concrete commitments about new assistance.

While domestic political maneuvering may have been at the top of McCarthy’s mind—he will need the Freedom Caucus’s backing to become speaker—his remarks made waves across the Atlantic.

David Arakhamia, a leading member of the Ukrainian parliament, responded with shock.

“Just a few weeks ago, our delegation visited the US and had a meeting with Mr McCarthy,” Arakhamia told the Financial Times. “We were assured that bipartisan support of Ukraine in its war with Russia will remain a top priority.”

Other Republican lawmakers have expressed a strong desire to continue funding military assistance to Ukraine.

“Nobody’s talking about a blank check,” Pennsylvania GOP Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick told Politico this week, saying Ukraine needs the money.

“This is a historical thing where war fatigue sets in, and this is the big risk. In fact, it’s something that Vladimir Putin banks on, that it’s no longer going to capture the front page of the newspaper,” he continued. “People are going to forget about it and the genocide will be ocurring in the darkness. We’re trying to prevent that.”

Just a few weeks ago, in an interview with The Dispatch, a senior House Appropriations Committee member struck a very different tone than McCarthy.

“He’s just wrong,” Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma said after Sen. Chris Murphy, a Connecticut Democrat, predicted Republican support for Ukraine would wane.

“In my experience around here, Republicans are a lot more likely to remain committed to a military project than Democrats are,” Cole added. “That was true in Iraq, that was true in Afghanistan, true with Vietnam. It was true throughout the Cold War from the ‘60s on. It’s certainly true here.”

While it’s unclear whether that dynamic will hold true in the House, it does among top Senate Republicans. It’s just one of the areas McCarthy could soon clash with Senate GOP Leader Mitch McConnell, who has been staunchly behind a firm response to the Russian invasion.

“There are a few voices on the right that seem to oppose the war, but the vast majority of us, certainly including myself, think defeating the Russians in Ukraine is high-priority,” he told Defense News last month.

McCarthy’s comments could prompt lawmakers to pass more Ukraine aid than they had initially planned after the midterm elections and before the new Congress convenes.

Lawmakers will consider an omnibus spending package, a must-pass defense authorization measure, Electoral Count Act reform, and a potential gay-marriage bill. Add Ukraine aid to the negotiations—along with murmurs about another measure we’ll get to next—and it’s shaping up to be a busy couple of months.

Could Congress Hike the Debt Ceiling in the Lame Duck?

Probably not.

In his interview, McCarthy also pledged to use a debt ceiling deadline next year to push Republican spending priorities. If anything goes wrong, it could lead to a default on U.S. debt—a historic moment that could trigger a global economic meltdown. (Very normal, standard stakes to be working with!)

Democrats realize they may be handing Republicans a loaded weapon next year if they don’t address it first, but lawmakers have little time and almost no momentum to raise or suspend the debt ceiling before the new Congress begins. I caught up with a couple congressional aides about this Thursday, and here are the dynamics they’re watching:

Democrats could theoretically push a new budget reconciliation package in the lame duck, which would allow a debt ceiling hike to pass absent Republican support. But that would require passing a new budget and holding two lengthy vote-a-ramas—a wide-ranging amendment process—in the Senate. At this point, congressional aides think there isn’t enough bandwidth to pull that off with all the other items Congress has on its to-do list.

Members of Congress also often need a firm deadline to act on a problem, and this deadline isn’t imminent by any means. It’s more of an abstract, future problem to dread. Democrats would have to do a lot of organizing in a short period of time to make reconciliation work.

The other challenge for this approach: Herding cats. If Republicans do well in the midterm elections, it could spook some moderate Democrats up for reelection in 2024. Democratic Sens. Jon Tester, Kyrsten Sinema, and Joe Manchin all could see political danger in supporting a debt ceiling hike in the lame-duck session. Democrats currently control the House by a few votes, and the Senate is evenly split. One Democrat with cold feet could end a debt ceiling reconciliation bill’s chances in the Senate.

Oh, and: The reconciliation rules would require Democrats to raise the debt ceiling by a dollar amount, instead of suspending it for a certain time period. That would give Republicans a concrete, massive price tag to point to in attacks on Democratic lawmakers.

The news cycle also plays into whether members would have enough momentum. Democrats would have to remain focused on the debt ceiling as a priority. Post-election news cycles are particularly hectic, as parties launch into leadership elections mode and newly elected members gear up to enter Congress.

The spending omnibus presents another (longshot) option. Congress will have to pass a government funding package in December, but attaching debt ceiling language to it would be a heavy lift. Democrats would need support from 10 Senate Republicans. To pull that off, aides predicted, McConnell would probably have to give his blessing. Why would he be inclined to do that, especially after his showdown forcing Democrats to hike the debt ceiling on their own last year?

Those are just a few reasons aides see slim chances for a debt ceiling bill before the end of the year. Still, one staffer said, some Democratic offices are “rattling the cages” to try to bring attention to the problem and get the ball rolling.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.