House Democrats are poised to impeach President Donald Trump this week, charging him with incitement of insurrection after a mob of his supporters violently overran the Capitol last Wednesday.

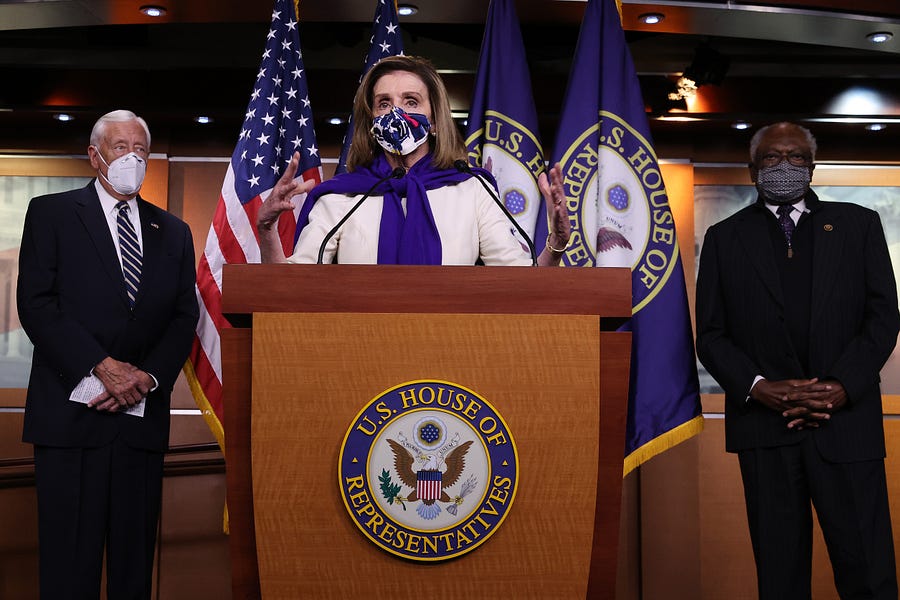

Democratic leaders plan to bring an article of impeachment forward for a vote tomorrow. It will likely be approved, and if it is, it will grant Trump an historic distinction: No president has ever before been impeached twice.

“President Trump gravely endangered the security of the United States and its institutions of Government,” the article, introduced by Rep. David Cicilline and co-sponsored by more than 200 Democrats, declares. “He threatened the integrity of the democratic system, interfered with the peaceful transition of power, and imperiled a coequal branch of Government. He thereby betrayed his trust as President, to the manifest injury of the people of the United States.”

Cicilline, a Rhode Island Democrat, announced Monday that enough Democrats have pledged their support for impeachment that it will pass in the House. A few House Republicans, such as Rep. Adam Kinzinger and freshman Rep. Peter Meijer, could also vote for it, but exact numbers are unclear.

GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy has made clear he is opposed to impeachment. He sent the conference a letter Monday explaining his position and laying out alternatives, like censuring Trump. But House Republican Conference Chair Liz Cheney, the third-ranking Republican, has publicly condemned Trump’s handling of the attack and potentially could support impeachment. She hasn’t announced a decision one way or the other.

Before the impeachment vote Wednesday, Democrats plan to pass legislation this evening urging Vice President Mike Pence to invoke the 25th Amendment to remove Trump from power. That doesn’t mean Pence and the Cabinet will actually do so; reports indicate Pence opposes using the 25th Amendment for now. (And Pence had a reconciliation meeting with President Trump Monday evening.) But keep an eye on the vote tally. Which Republicans choose to support the measure may give us a better sense of who could vote to impeach Trump on Wednesday, though some members may feel more comfortable voting for the 25th Amendment legislation than impeachment.

Even if impeachment advances in the House as expected, it remains unlikely that Trump will actually be removed from office in the waning days of his presidency. Despite stirrings of support for impeachment among some GOP senators, it’s doubtful enough of them would vote to convict Trump at this point.

The Senate is on recess until January 19, the day before President-elect Joe Biden will be inaugurated. To come back early under normal procedures would require consent from every senator, including Trump’s staunchest supporters in the chamber. That is not going to happen, and without such a move, the trial would be pushed until after Trump vacates the presidency.

But there might be a workaround: The Washington Post’s Seung Min Kim reported Monday that Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer is looking into an emergency authority that would allow leaders to reconvene the Senate early, without necessarily having the support of all senators. This would hinge on whether Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell agrees to bring back the chamber. There’s no indication so far that he would be willing to support the move. (Schumer is still minority leader at this point, and McConnell is still majority leader, because the two Democrats who won Senate seats in Georgia last week have not yet been sworn in.)

Biden and his allies have expressed concerns about the trial impeding other Senate business in the early days of his administration, such as approving his nominees and moving forward with additional coronavirus relief. House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn has suggested holding onto the article of impeachment and sending it to the Senate at some point later, like after the first 100 days of Biden’s presidency. But some top Democrats, including House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, have pushed back on that notion, preferring to send impeachment to the Senate right away. Once the House passes the impeachment to the Senate, the Senate is compelled to act on it right away.

Delaying the vote could risk losing Republican support for the effort. Many Democrats have argued that Trump’s removal is not just necessary but urgent. If they delay the trial to prioritize Biden’s agenda, some Republicans may rightly view the move as political, making it harder for them to support conviction.

Biden said Monday that he hopes a balance can be struck in which the Senate would spend mornings on nominees and legislative business, while afternoons would be reserved for the impeachment trial. He told reporters he has already discussed the matter with a number of senators and is awaiting further guidance from the Senate parliamentarian.

What to Expect in a Democratic Senate

Last week, Democrats won both Senate seats in Georgia. That upset outcome sets up a 50-50 chamber, with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris acting as tiebreaker—tipping control of the Senate to Democrats.

This has massive implications for the kinds of bills that will be considered and become law over the next two years, as well as the confirmation of Biden’s executive and judicial nominees. Democrats will now be able to pursue some legislation Republicans oppose—think another round of coronavirus relief—using the same process the GOP employed to advance their 2017 tax bill. (More on that below.) They will also have the power to bring bills to the floor that have the potential to garner 60 votes for passage, such as proposals on immigration and expanding background checks for gun sales.

Senate leaders have not yet announced a specific date for swearing in John Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, as the state of Georgia has to certify the results first. They are expected to take office about the same time President-elect Joe Biden is inaugurated, though: Georgia’s deadline for certifying the results of the election is January 22.

With a 50-50 breakdown, Democrats will have to remain unified in order to advance agenda items. The dynamic gives more power to rank-and-file members, much like the House’s slim majority. (Hence the Joe Manchin memes.)

The Senate has been evenly split only a few times in the country’s history. Most recently, it was tied for several months in 2001. In that instance, the two party leaders negotiated a power-sharing agreement to avoid heated battles over small procedural issues. That agreement provided for the majority to control committee chairmanships, but it ensured committees would be evenly divided between the two parties. The rules also allowed for full Senate consideration of legislation that didn’t make it out of committee because of a tied vote.

In 2016, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said he believed Senate leaders would “simply replicate” the agreement made after the 2000 election if the chamber were to become evenly split once again. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has not specified what approach he plans to take since winning the two Georgia seats, although he said he looks forward to sitting down with McConnell to discuss the matter. It’s probable the two are already negotiating the details behind the scenes.

“I assume in the next couple weeks, Schumer and Mitch will sit down and kind of figure out how this is going to work,” Sen. John Thune, the second-ranking Senate Republican, told reporters recently.

With the majority, Democrats will have a great deal of power to set the agenda, exercise oversight, and pursue priorities simply by virtue of leading committees. Democratic-socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders is set to chair the Senate Budget Committee. Progressive Sen. Sherrod Brown will now head the Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee. Their priorities as chairmen will be worlds apart from what their Republican counterparts had planned.

Democratic leaders will also have the ability to pursue action on bills that have stalled over the past several years, like proposals to protect undocumented immigrants who were brought to the United States as children. Sixty votes are needed to pass most measures in the Senate, meaning support from only 10 Republicans will be required to pass legislation Democrats are in agreement about. Still, it can be extraordinarily difficult to reach that threshold when dealing with controversial issues.

There is a procedural tool for circumventing the 60-vote threshold: budget reconciliation. The process allows for the passage of legislation with only a simple majority in the Senate. These bills have to follow a certain set of rules about what kinds of policy items can be addressed, primarily allowing measures that affect revenue and spending. Republicans used reconciliation to pass their 2017 tax bill. It was also the vehicle for their failed attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Reconciliation requires passage of a budget resolution first, and the number of times the procedure can be used over a relatively short time frame is limited. It’s not exactly clear how many times Democrats could use reconciliation before the 2022 midterms, but some experts have pointed out they could potentially advance three budget resolutions over the next two years.

Democrats will have to choose how to sequence their agenda items, whether that includes a health care bill, an infrastructure package, or something different. For now, coronavirus relief is at the top of the list.

Schumer said after the victories in Georgia that his first concern is to deliver $2,000 checks to Americans. Republicans repeatedly rejected efforts to pass stimulus payments of that amount. The checks could be wrapped into a larger coronavirus aid reconciliation package including Democratic priorities such as funding for state and local governments and an extension of federal unemployment benefits.

Progressives, who don’t want to rely on the budget reconciliation process or compromise with Senate Republicans, have called for Democrats to get rid of the 60-vote threshold for passing most bills. It would take only a simple majority to do so, but several Democrats, including West Virginia’s Joe Manchin and Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, have said they oppose such a move.

“We Senate Democrats know we face one of the greatest crises Americans have,” Schumer told reporters when asked about getting rid of the filibuster last week. “We’re united in wanting big, bold change, and we’re going to sit down as a caucus and discuss the best ways to get that done.”

We Need Transparency From Law Enforcement

The U.S. Capitol Police force is fairly opaque in normal times, but the organization’s unwillingness to offer information to the public and its refusal to answer questions from reporters after last week’s mob takeover of the Capitol has been especially alarming.

There haven’t been any sort of regular briefings—from the Capitol Police, the White House, the Justice Department, the Department of Homeland Security, or anybody else—about the ongoing investigation into the attack on the Capitol or findings so far about what happened. Information has largely been coming from media reporting and members of Congress who are looking into what went wrong on Wednesday.

Just yesterday, reporters first learned from Ohio Democratic Rep. Tim Ryan, who chairs the subcommittee that oversees funding for the Capitol Police, that two Capitol Police officers have been suspended. He also said—though he was unclear on details—that someone involved in the response to the attack, either a Capitol Police officer or a National Guard member, had been arrested, and more than a dozen officers are under investigation for their behavior during the attack.

His office later corrected his remarks, after dozens of reporters tweeted and wrote about them, saying that no officers have actually been arrested. Ryan’s briefings, which often come after his own information-seeking phone calls with federal officials and law enforcement, have been the only effort so far to regularly provide updates to reporters. But it’s not ideal to be receiving information of such magnitude secondhand.

Reporters are definitely fed up with the lack of transparency from the Capitol Police and other federal agencies involved in the aftermath. So are lawmakers.

Rep. Jason Crow, a Colorado Democrat, told CNN on Monday night that he is “very angry” no briefings have occurred since January 6.

“It is far past time for our national security officials and our law enforcement to start communicating the nature of this threat,” he said.

Good Reads

We hope you are enjoying Uphill. To ensure that you receive future editions in your inbox, opt-in on your account page.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.