Good morning. We’re still coping with the fallout of last week’s attack on the Capitol. Here in D.C., many of the roads around the building are being closed ahead of President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration. Thousands of members of the National Guard have been tasked with protecting the Capitol, and fencing has been erected around government buildings in the area.

As inauguration approaches, members of Congress are also preparing for a heated trial after the House impeached President Donald Trump for incitement of insurrection this week. The trial could begin about the same time Biden is inaugurated Wednesday. For this edition of Uphill, my colleague Andrew Egger has helpfully explored some of the logistical questions at play.

The Impeachment Logjam

A presidential impeachment trial is a weighty affair, so it’s not surprising the rules that govern how the Senate tackles one are constructed to ensure it gets lawmakers’ full attention. The body is compelled to drop almost everything to consider the matter: From the day after the article (or articles) are presented to them, senators must attend to them six days a week “until final judgment shall be rendered, and so much longer as may, in [their] judgment, be needful.” If other business is pressing, the Senate must find ways to wedge it in around the time demanded by the trial.

These exacting requirements can sometimes create logistical difficulties. During President Trump’s first impeachment, several Senate Democrats who were running for president found themselves chained to their desks in Washington rather than storming around the campaign trail in the weeks prior to the Iowa caucuses.

That was a headache for only a few presidential hopefuls; this time, the schedule threatens to create a mess for the new Biden administration. The earliest date the House can present the Senate with its article of impeachment is next Tuesday, January 19, when the Senate comes back into session. If the House moves as quickly as possible, the trial would begin on January 20: Biden’s inauguration day.

This is more than just a PR frustration for Biden’s team. The opening weeks of a presidential administration are usually a flurry of activity in the Senate, which is tasked with confirming the new president’s nominees for top posts around his government. Having to work that in around a demanding impeachment schedule threatens to create a significant congressional logjam—and that’s before you factor in a fight over the massive new COVID stimulus Biden wants to pass.

According to Senate rules, calling senators back from their recess early to begin proceedings would require one of two things: either unanimous consent of the entire body, or an emergency agreement between Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. (Their roles will soon reverse when the two Democrats elected in Georgia are sworn in.)

Unanimous consent is a non-starter: GOP senators who opposed impeachment in the first place aren’t about to help speed it along. And although Schumer called on McConnell to agree to reconvene under emergency circumstances, McConnell declined to do so, saying a trial will last longer than Trump is in office anyway.

It’s one thing to fire off a lightspeed impeachment in the House, which is an inherently political process. But a Senate trial is, well, a trial—although politics undeniably plays a large role here as well, justice requires that those sitting in judgment take time to consider the evidence for and against the charges, and that the accused have time to assemble and then make his defense. President Trump’s first trial, the shortest presidential impeachment trial in history, lasted three full weeks—and would have gone longer had Senate Republicans not barred Democrats from calling new witnesses.

House Democrats have considered the possibility of withholding the article of impeachment until the Senate has gotten a good jump on its confirmation work. But that decision would stand awkwardly beside the decision to proceed so speedily with impeachment in the first place, and it would risk making the trial seem like an afterthought as Trump leaves office and recedes from view. House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer has repeatedly said he would prefer to send the article to the Senate immediately, although the final decision is up to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. She may address the question of timing at a press conference later this morning.

Biden has called on the Senate to “bifurcate” its schedule, taking care of the trial and regular business each in turn. Because by rule trial proceedings start every day at noon, that would mean attending to confirmation and legislation in morning sessions.

“I hope that the Senate leadership will find a way to deal with their Constitutional responsibilities on impeachment while also working on the other urgent business of this nation,” Biden said this week.

According to the New York Times, McConnell has told Biden that whether such a move is possible must be determined by Senate Parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough, the official whose role it is to advise the Senate on such procedural matters. Even if McConnell is on board, the path to a bifurcated schedule isn’t clear. Some have suggested that this move, too, would require another unanimous consent approval, which could prove difficult to obtain.

This sort of procedural talk might make your eyes glaze over, but this question is actually very important. If the parliamentarian rules that the two-track system requires unanimous consent, then any single senator with an axe to grind against the trial would have the ability to gum up all the rest of the Senate’s business in protest against the proceedings. If she rules otherwise, McConnell and Schumer would be able to strike a deal that would lead to an extremely busy February in the Senate—but one that will avoid leaving Biden’s Cabinet nominees congealing on the back burner.

Biden Announces Economic Relief Plan

Biden announced details of an ambitious coronavirus relief proposal on Thursday night, saying he hopes it can win support from congressional Republicans.

But with most GOP senators wary of new federal spending on another round of economic aid, and with an impeachment trial pending, quickly passing Biden’s stimulus package is expected to prove a challenge. The plan also includes items Republicans are certain to balk at, such as raising the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour.

The $1.9 trillion framework touts funding for COVID-19 testing, schools, and vaccine distribution. It also directs $350 billion to state and local governments, a long-held Democratic priority. It would boost federal unemployment benefits from $300 to $400 per week and extend them through September. It would also increase the child tax credit from $2,000 to $3,000 per child this year, with an additional $600 for children under the age of 6.

The plan comes as many Americans continue to suffer from the economic impacts of the raging pandemic. Nearly 1 million people filed for unemployment last week.

“I know what I just described does not come cheaply,” he said while outlining his priorities Thursday evening. “But failure to do so will cost us dearly.”

Biden’s proposal would also send direct payments of $1,400 to most Americans. This aspect of the package has some Republican support; earlier this week, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio called for Biden to prioritize boosting the $600 direct payments when he takes office.

“It would send a powerful message to the American people if, on the first day of your presidency, you called on the House and Senate to send you legislation to increase the direct economic impact payments to Americans struggling due to the pandemic from $600 to $2,000,” Rubio wrote in a letter.

He added that he has concerns about “the long-term effects of this additional spending,” but “we simply cannot ignore the fact that millions of working class families across the nation are still in desperate need of relief.”

Rubio poured cold water on the nearly $2 trillion proposal Thursday night, though, writing that it won’t be able to pass Congress quickly. He made the case for a more targeted approach.

Some progressives, meanwhile, have taken issue with the effort for their own reasons, calling for the bill to advance new full payments of $2,000 to most Americans instead of checks totaling $1,400.

A sizable number of Democrats also want to see legislation that ensures recurring monthly $2,000 checks until the pandemic ends, not just a one-off payment.

“Let’s not just give ordinary Americans a one-time $2,000 check,” Rep. Ro Khanna, a California Democrat, said Thursday afternoon. “With our new majority and a worsening crisis, let’s meet the need: $2,000/month, every month, until this crisis is over.”

Biden promised a more sweeping proposal will follow, which Democrats could try to pass through budget reconciliation. Reconciliation allows the party that controls the Senate to approve legislation with a simple majority instead of 60 votes. There are rules that limit the kinds of policies that can be included in reconciliation bills, though, complicating any such attempt.

Biden has said he hopes to pass his initial $1.9 trillion plan under regular order instead of reconciliation, meaning he would need support from at least 10 Republicans in the Senate. Unless this package changes substantially in the coming weeks—cutting items like the minimum wage hike and funding for state and local governments—it’s difficult to imagine that happening.

Many GOP senators are likely to recoil at the price tag of the proposal. Republicans resisted Democratic calls for more than $2 trillion in relief for months leading up to the November election. In December, Congress passed a $900 billion compromise package.

Democrats at the time said it was only a short-term measure to keep the economy afloat until more relief could be approved under the Biden administration.

“As I said when it passed in December, a bipartisan COVID-19 relief package was a very important first step. I’m grateful for the Democrats, Republicans, and independent members of Congress who came together to get it done,” Biden said Thursday. “But I said at the time it’s just a down payment. We need more action, more bipartisanship, and we need to move quickly. We need to move fast.”

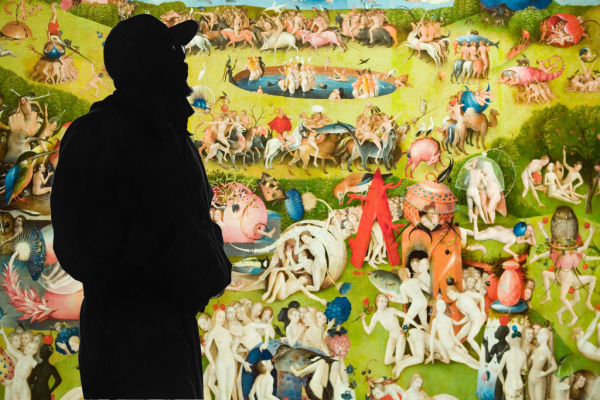

Presented Without Comment

Good Reads

To ensure that you receive Uphill in your inbox, be sure to opt-in on your account page.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.