On March 23, 2019, the U.S., its Western allies and local partner forces liberated the last town held by the Islamic State (or ISIS) in eastern Syria. That town, a ramshackle location named Baghouz, was the final stronghold for the so-called caliphate’s men.

At the height of their power in the summer of 2014, ISIS loyalists controlled a contiguous amount of landmass roughly the size of Great Britain. They ran sharia (Islamic law) courts and meted out barbaric punishment, while indoctrinating children in their “Cubs of the Caliphate” program. They collected taxes from the local population, while plotting spectacular terrorist attacks in the Europe and inspiring others in America. They were building a dystopian empire based on fear, zealotry and a lust for power.

Less than five years later, the caliphate had been dismantled.

One year after the fall of Baghouz, how strong is ISIS today? It’s a straightforward question. But the answer isn’t so simple.

There’s no question that the one-time caliphate is well-removed from the zenith of its power. The organization expended much of its manpower and many of its resources defending its territory, including its twin capitals of Mosul, Iraq and Raqqa, Syria, both of which were liberated in 2017. But ISIS hasn’t been entirely vanquished either. The group’s leaders knew well in advance that their caliphate would crumble, and they took steps to fight on, returning to the jihadists’ insurgent roots.

ISIS also retains a worldwide network of terrorist and insurgency organizations that are still loyal to its top leader, a man known as the “Emir of the Faithful” to the true believers. To assess the cohesion and potency of this global network, we’ll briefly examine four variables: the status of ISIS’s leadership and overall command structure; the extent of its warfighting capacity in Iraq and Syria; the viability of its affiliates (or so-called provinces) elsewhere; and the resiliency of its media operations.

The bottom line: One year removed from the fall of Baghouz, ISIS is far from dead.

The ISIS leadership and command structure.

On October 26, 2019, the U.S. finally caught up with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. For his tens of thousands of followers around the globe, Baghdadi was known as “Caliph Ibrahim”—the would-be ruler of an Islamic empire. However, Baghdadi didn’t rule over any ground at the time of his death. Instead, he was found in the northwest Syrian province of Idlib—a somewhat surprising location, given that Idlib is ruled by Baghdadi’s jihadist foes and had never been part of his caliphate.

ISIS quickly named Baghdadi’s successor as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi, an alias that is intended to highlight his supposed familial ties to the Prophet Mohammed’s Quraysh tribe. The group hasn’t provided a biography for its new emir, so many details about the man remain murky. In mid-March, the U.S. government officially identified Abu Ibrahim as an Iraqi named Muhammad Sa’id Abdal-Rahman al-Mawla, also known as Hajji Abdallah, among other aliases.

We’ll call him Hajji Abdallah (pictured above) for the sake of brevity. The son of an Iraqi Turkmen family, Abdallah is a jihadist veteran whose career dates back to the days of al-Qaeda in Iraq. A notorious ideologue, Abdallah’s religious writings have been used to justify ISIS’s atrocities. According to the State Department, Abdallah has “helped drive and attempt to justify the abduction, slaughter, and trafficking of Yazidi religious minorities in northwest Iraq and oversees the group’s global operations.”

Abdallah (or Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurayshi) isn’t a household name like Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, but he still retains the loyalty of thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of fighters. And it isn’t at all clear how impactful Baghdadi’s death really was.

The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), which is part of the Pentagon, assessed following Baghdadi’s death that it had little effect on the ability of ISIS to “maintain continuity of operations, global cohesion, and at least its current trajectory.” Similarly, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), which oversees the war against ISIS, found that “ISIS remained cohesive, with an intact command and control structure, urban clandestine networks, and an insurgent presence in much of rural Syria” following Baghdadi’s demise. The DIA and CENTCOM also agreed that the death of Baghdadi “did not result in any immediate degradation to ISIS’s capabilities.”

Part of the problem is that ISIS has built a command-and-control structure that is far deeper than its top leader. The U.S. and its allies have worked to degrade this hierarchy, but there is a basic epistemological problem at the heart of the war against ISIS. No one is really sure how many leaders the group started out with in 2014, when the current U.S.-led campaign began, nor is it clear how many replacements ISIS had ready and waiting to take over when their superiors fell. There is also much uncertainty concerning the innerworkings of ISIS’s management structure. For example, it is known that the group established a series of committees, each with its own dedicated responsibilities. But there is no firm evidence showing that these bodies have been interrupted, let alone demolished. Meanwhile, there is much evidence that Abdallah and his subordinates still command an army in Iraq, Syria and beyond.

The insurgency in Iraq and Syria.

The ISIS caliphate grew out of al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)—an insurgency organization that, in its various incarnations, has fought against the U.S., the Iraqi government and their allies from 2003 onward. In 2006, AQI rebranded twice, declaring late in the year that it was now to be known as the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). The ISI was intended to serve as the “cornerstone” of a new caliphate, according to its inaugural message. That ambition was briefly realized in the form of Baghdadi’s self-declared Islamic empire. After the dissolution of Baghdadi’s nascent state, it was only natural that ISIS would return to its insurgent roots. And indeed, the group’s remaining jihadists melted away from the more urban areas of Iraq and Syria, returning to the mountains and deserts from which they emerged in 2014.

It isn’t clear how many fighters ISIS has in Iraq and Syria today. In mid-2019, the U.S.-led military coalition (Combined Joint Task Force—Operation Inherent Resolve, or CJTF-OIR) estimated that ISIS still had between 14,000 and 18,000 “members,” including “fighters,” across Iraq and Syria. But there are lots of problems with these figures. The distinction between “members” and “fighters” is fuzzy. Other estimates are either higher—or lower. The truth is that no one really knows how many ISIS fighters remain in the field. Regardless, the organization clearly has enough capacity to continue launching multiple attacks across Iraq and Syria each week.

ISIS controls little to no ground inside Iraq today, but instead functions as a hit-and-run operation. According to CJTF-OIR’s most recent reporting, most of ISIS’s attacks in Iraq are focused north and west of Baghdad, in the provinces of Diyala and Kirkuk. A “seam” has developed because of a territorial dispute between the Kurdish Regional Government, based in Erbil, and the central government in Baghdad. As a result, a pocket of ground remains outside the control of both Kurdish Peshmerga forces and the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) under Baghdad’s control. Kurdish officials have repeatedly warned that the ISIS diehards operating in this “seam” are conducting a persistent campaign of assassinations and other low-grade attacks that are intended to weaken local security.

As in Iraq, ISIS is nowhere near the peak of its power in Syria. But the group continues to function as an insurgency, conducting operations mainly in the north and eastern parts of the country. Most of ISIS’s claimed attacks take place in the provinces of Deir Ezzor, Hasakah, Raqqah and Homs. The jihadists are fighting both America’s local partners, known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), as well as the Assad regime and its allies.

Just this week, ISIS reminded the world how brutal its tactics are by producing a 28-minute video highlighting its operations inside Syria. The production contains graphic footage of Assad loyalists being slaughtered like lambs in eastern Syria. It also features extensive footage of ISIS’s warfighting, including with “technicals”—that is, heavily armed trucks with large guns mounted in the beds. One such image can be seen above.

The U.S.-backed SDF has a tenuous hold on a makeshift network of camps where ISIS fighters and their family members are held. One of these camps, Al Hol, is especially problematic, as ISIS members have established sharia courts and other rudimentary governance even while being imprisoned there. Tens of thousands of men, women and children are held at Al Hol, but there are just several hundred security personnel—meaning the situation is potentially combustible. In recent days, ISIS reportedly staged a jailbreak at one of the other facilities, though it isn’t clear how many jihadists escaped.

In the final months of his life, Baghdadi called on his followers to free their imprisoned comrades from prisons around the world. Other senior ISIS members have reiterated his plea. Indeed, ISIS has repeatedly revitalized its organization by springing its firebrands from jails—including men who went on to lead the caliphate. Baghdadi himself was once held by the U.S. at Camp Bucca in Iraq, as were many of his senior lieutenants.

The ISIS provinces.

Outside of Iraq and Syria, ISIS established a number of self-described “provinces.” These are supposed to be territorial appendages to the mother caliphate. However, just as in Iraq and Syria, the ISIS provinces control little ground today.

After Hajji Abdallah was named as Baghdadi’s successor late last year, ISIS provinces and cells in Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Central Africa, East Asia (the Philippines), Kashmir, the Khorasan (Afghanistan and parts of the surrounding countries), Pakistan, the Sinai, Somalia, Tunisia, West Africa and Yemen all quickly affirmed their allegiance to the new would-be caliph. Their continued allegiance was memorialized in a series of videos and released online, many of which showed small bands of men locking hands as they pledged their undying fealty to Abdallah.

Some of these ISIS branches are nothing more than small-time terrorist outfits, but others are prolific actors, capable of killing and wounding hundreds of people each week.

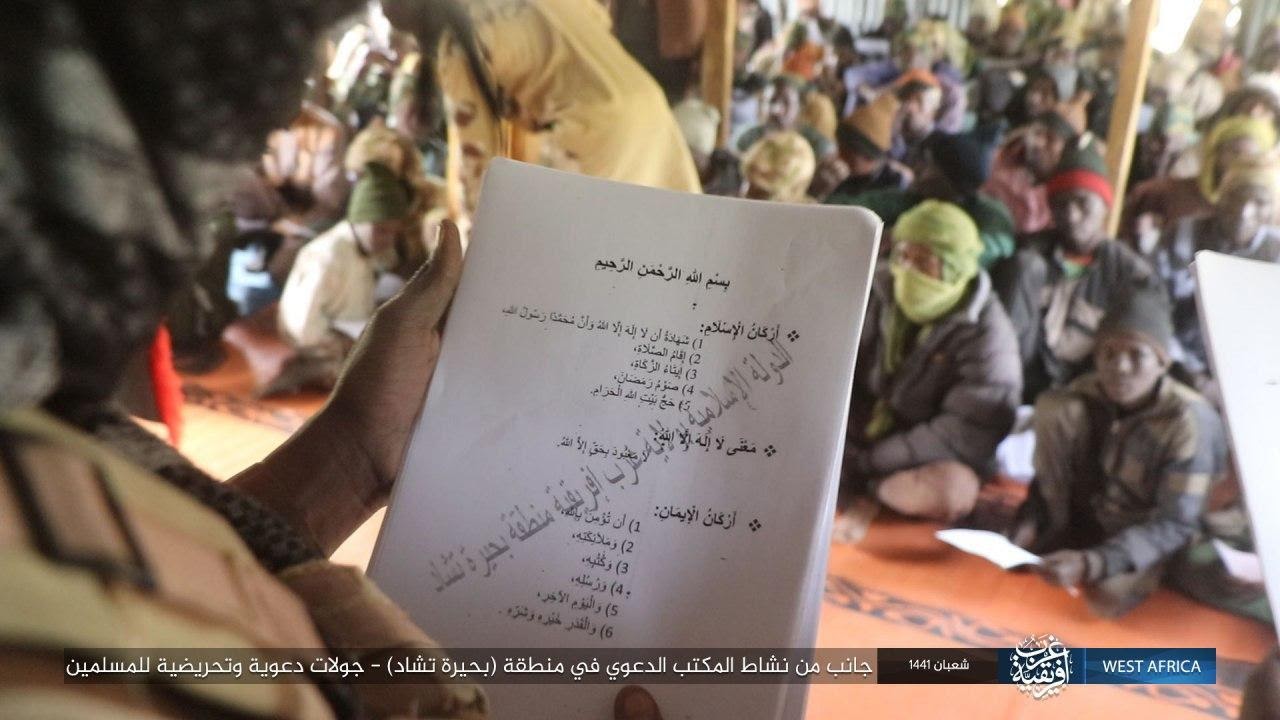

West Africa has become a hotbed for both ISIS and its rivals in al-Qaeda. Although al-Qaeda’s men appear to be more numerous there, ISIS has an entrenched footprint. ISIS has wings in the Greater Sahara and West Africa that attack local forces virtually every day. Malian and Nigerien forces have suffered hundreds of casualties in recent months, while the jihadists also terrorize local Christians and Muslims. According to the U.N. Security Council, there were more than 4,000 civilian and military deaths in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger in 2019—as compared to just 770 in 2016.

Elsewhere, such as in Afghanistan and Somalia, ISIS has suffered setbacks. But ISIS isn’t out for the count in those locales.

On March 25, for instance, an ISIS terrorist known as Abu Khalid al-Hindi stormed into a Sikh temple in Kabul, killing more than two dozen people and wounding dozens of others. ISIS has lost ground in eastern Afghanistan, as two campaigns—one by the U.S. and Afghan government, and another by the Taliban—have depleted the group’s ranks. But al-Hindi’s attack was just the latest in a string of ISIS operations inside the Afghan capital. And his alias, al-Hindi, indicates that the terrorist was originally from India or India-ruled Kashmir—an ominous indication of ISIS’s regional designs. Indeed, the group claimed that the attack in Kabul was intended to avenge the Muslims in Kashmir, where another small band of jihadists remains loyal to Abdallah.

The ISIS media machine is also still prolific.

In November 2019, the European Police Agency (EUROPOL) initiated an effort to disrupt ISIS’s robust presence on Telegram—a messaging application that offers both private, encrypted communications, as well as public postings. Telegram cooperated with this effort, banning thousands of channels and bots (which regenerate channels after they are taken down) that were either run by ISIS or its supporters. While this campaign interrupted ISIS’s media operation, it was far from a decisive blow.

ISIS has been adept at using multiple social media and messaging applications at once, so even if it loses its presence in one outlet, it has several others already going. Therefore, after Telegram moved against the organization, ISIS simply used other social media applications and sites to get its messages out, including relatively new entrants such as Riot and Hoop. ISIS also redoubled its efforts to generate content on older platforms like Twitter and Facebook, with limited success. The end result of the Telegram crackdown is dubious. Telegram itself has been forced to ward off an ISIS resurgence on its own platform.

The reality is that while ISIS may not be creating as much content as it once did, its primary propaganda arms are still prolific content creators. One of them is Amaq News Agency—ISIS’s daily reporting service, which shares videos, statements and photos everywhere from West Africa to Afghanistan on a daily basis. ISIS also publishes a weekly newsletter known as Al-Naba, which summarizes current events from the jihadists’ perspective and highlights their worldwide terrorist attacks. Al-Naba’s most recent editorials have been focused on the coronavirus pandemic, portraying the virus as Allah’s retribution—notwithstanding the fact that COVID-19 doesn’t discriminate between believers and infidels. Other ISIS media outfits publish on a less frequent basis but remain active as well.

The U.S. and its allies have systematically targeted ISIS media operatives with airstrikes and in other operations as part of an attempt to stymie the jihadists’ propaganda output. It is difficult to measure the efficacy of this campaign, but it is easy to see that the ISIS media machine has survived.

I follow ISIS’s media output as part of my own work. Indeed, when Telegram banned ISIS channels late last year, it mistakenly shut down several of my own accounts. It took more than three weeks for my accounts to be restored, and only after I assured (and reassured, multiple times) Telegram’s staff that I’m not an ISIS recruiter or sympathizer. When my channels were reinstated, I was surprised to learn that hundreds of jihadists I follow were still active. That is, whereas I temporarily lost my channels—they hadn’t lost theirs. Some of the figures who remained on Telegram during this entire time have been designated as terrorists by both the United Nations and the U.S.—meaning they are hardly obscure men. Yet, they’ve been on Telegram for years without interruption.

I pass along the anecdote above as a way of explaining why I’m skeptical of the West’s cumulative efforts to break ISIS’s propaganda mill. In the past week alone, Amaq published dozens of messages, including: photos of the jihadists’ proselytization efforts in West Africa; Abu Khalid al-Hindi’s video will; written reports and images documenting attacks by ISIS-affiliated militants in Central Africa; and other statements and images from Iraq and Syria.

From my vantage point, ISIS has successfully retained much of its online media machinery.

ISIS fights on.

In sum, ISIS fights on. While it is unlikely that the would-be caliphate will ever amass the power it once had, the organization is resilient and determined to continue terrorizing all of its foes. It remains to be seen how much ISIS can take advantage of President Trump’s desire to “end” the “endless wars.” While ISIS grew out of the March 2003 U.S.-led war against Saddam Hussein’s regime, it was only because the U.S. intervened once again in 2014 that the jihadists lost their hellish state. But America’s role is very much in doubt, as both Trump and some of his Democrat rivals have no patience for indefinite conflicts.

In contrast, ISIS’s men are first and foremost insurgents—meaning long wars are their specialty.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.