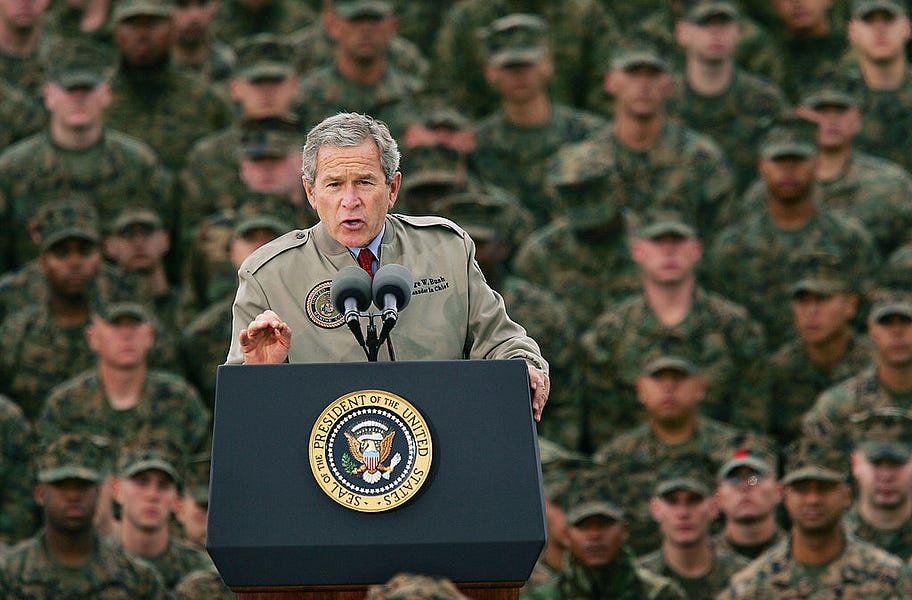

Congress has decided to begin cleaning out its “war powers” closet after years of accumulating Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) whose expiration dates seem long past due. In mid-June, the House voted 268-161 in favor of repealing the 2002 AUMF that authorized then-President George W. Bush “to defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq.”

Having removed Saddam Hussein from power and declared an end to combat operations in Iraq a decade ago, repeal seems to be a reasonable step for Congress to take. And it has considerable bipartisan support: 49 Republican House members voted for the measure. Even the relatively hawkish Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wisconsin) says, “The 2002 AUMF is no longer relevant.” Indeed, Gallagher, along with Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Virginia) and Rep. Jared Golden (D-Maine), have proposed repealing the First Gulf War AUMF (1991) and the Middle East Resolution of 1957—a resolution that stipulated that the president had the discretion to use American military force to assist a nation if it requested assistance to fend off “armed aggression from any country controlled by international communism.”

As for the Senate, in early March, Sens. Tim Kaine (D-Virginia) and Todd Young (R-Indiana) introduced a bill to end both the 1991 and 2001 AUMFs. In the wake of the recent House vote, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer indicated he would make every effort to bring the lower chamber’s measure to the Senate floor as well. Not to be outdone by Gallagher, Kaine, and company, Sens. Mike Lee (R-Utah), Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) and Chris Murphy (D-Connecticut) are proposing a wide-ranging bill to repeal not only the 1957 joint resolution and the two Iraq AUMFs, but also the 2001 AUMF that authorized the president “to use all necessary and appropriate force” against the terrorists involved in the “attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001” or who had “harbored” them.

Given the crowded legislative agenda, in the near term, it’s likely that only the 2002 AUMF will be voted on. But will its repeal matter? Well, yes and no. “Yes” for the simple reason that having a law on the books that no longer applies is evidence of a disrespect for the idea of law itself. Laws should be taken seriously, but they won’t be if they obviously no longer make sense or if their continued use is dependent on tortured interpretations. In 2017, for example, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis argued that repealing the 2002 AUMF “could call into question the President’s authority to use military force to assist the Government of Iraq both in the fight against ISIS and in stabilizing Iraq following the destruction of ISIS’s so-called caliphate.” Turning an AUMF whose object is dealing with the threat posed by Iraq into an AUMF to defend Iraq is precisely the kind of legal reasoning that gives a bad name to both “legal” and “reasoning.”

However, repealing the AUMF is unlikely to make a difference in practice. The Iraq AUMF has not been cited by either the current administration or the two previous administrations as key to legitimating combat operations in Iraq. In 2014, President Obama argued that the airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq and Syria were principally authorized by the 2001 AUMF, with the 2002 AUMF serving only as a possible “alternative” authority. Similarly, in 2020, the Trump team justified the killing of the leader of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, Qassem Suleimani, in Iraq, first with the Constitution’s Article II commander-in-chief power, and second with the 2002 AUMF.

In the case of President Biden’s February and June airstrikes against Iran-backed militias in Syria and Iraq, the administration has narrowed the authority to the Constitution. As Pentagon spokesman John Kirby put it rather succinctly, “As a matter of domestic law, the president took this action pursuant to his Article II authority to protect U.S. personnel in Iraq.” Really, no surprise here. The president has backed repeal of the 2002 AUMF and apparently believes that, between his Article II powers and the 2001 AUMF, he has all the legal authority he needs to conduct operations in Iraq either to protect American personnel or strike remnants of ISIS in the region.

To be clear, however, reliance on the 2001 AUMF and on Article II, as currently interpreted, is not without its problems. As numerous commentators have noted, the 2001 AUMF has been read by successive administrations to authorize not only combat operations in Afghanistan to deal with the Taliban and al-Qaeda but also the global war on terror in the broader Middle East and North Africa. However, the AUMF begins by stating that the purpose of the resolution is “to authorize the use of United States Armed Forces against those responsible for the recent attacks launched against the United States” with the goal “to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons,” with those entities being specifically tied to the planning, assistance, or operations “that occurred on September 11, 2001.” To square the circle of the resolution’s two goals with more expansive operations, the Obama administration argued it retained the executive discretion under the AUMF to include other terrorist organizations, such as ISIS, as al-Qaeda “associated forces.” While perhaps not as much of a stretch as what has occurred under the Iraq AUMF, it’s still a stretch since many of these jihadist groups did not exist on 9/11.

More problematic are current and recent administrations’ readings of their Article II powers. It would be reasonable for a president to argue that he has the constitutional authority to engage in combat operations to defeat a terrorist group who has declared war in some fashion on the United States, its citizens, or its military. But that is not what the past few presidents have argued. Instead, they have argued that they have the authority under the Constitution to send forces into harm’s way to protect America’s “national interest.” This has sometimes been tailored to fit only what presidents have called “limited” military operations, but even under that umbrella, the Obama team argued that it did not need congressional authorization for its campaign against Libya in 2011. Assuming they have the discretion to deploy the military to protect important national interests abroad is a pretty expansive hunting license for presidents to be carrying around.

A no less expansive response to this assertion of presidential authority is the Lee, Sanders, and Murphy proposal mentioned above. Titled the “National Security Powers Act of 2021,” Title I of the measure would not only repeal the existing AUMFs but would greatly expand Congress’ control over the authorization of military actions. In addition to an extensive list of reporting requirements (circumstances, cost, scope, duration, objectives, partners, risk, and the slightest addition of military personnel to a mission) to Congress whenever U.S. forces might be involved in hostilities, the would-be law attempts to eliminate the loophole by which recent presidents have denied that the existing War Powers Act has been triggered by narrowing the term “hostilities” to operations that essentially have to include ground forces.

The new measure would expand the definition of “hostilities” to include any lethal use of force in any domain; and it stipulates that the president’s constitutional authority to employ the military in any hostilities or deploy them where they might face hostilities must rest on either a declaration of war or a specific statutory authorization, or be in response to a “sudden attack, or the concrete, specific, and immediate threat of such a sudden attack.” Even in the last case, the president would still need to seek authorization from Congress within seven days to continue military operations and, absent that okay, would need to pull forces out of harm’s way after no more than 30 days.

Under the terms of the bill, the authorizations would automatically terminate after two years, unless renewed, and any expansion of the military mission will require a new authorization. Even train-and-assist missions, where hostilities are occurring but do not involve U.S. combat forces, would require specific authorizations.

The key assumption here is that the Congress has the first and last say when it comes to war. But that was never the Founders’ view. Although they certainly expected Congress to have the deciding hand in whether the country moved from a state of peace to a state of war against another nation, they understood the executive as having both the discretion to respond to credible threats to the country, its citizens, and its forces and the kind of institutional qualities—decisiveness and unity—to deal with a broad world in which changing circumstances rule rather than the law. Lee, Sanders and Murphy want to cabin that discretion and ignore the qualities the American presidency was meant to bring to the table in security and military affairs. Put simply, their bill is overkill.

The fact is, since the Korean War, and outside of the Panama and Grenada campaigns where U.S. citizens were under threat, presidents have not engaged in major conflicts without congressional sanction. Rhetoric about their Article II powers aside, presidents know that the politics of going to war are best served by getting Congress onboard. A more modest measure that would address current concerns about the somewhat slippery slope of the global war on terror would be a new AUMF for the war on those jihadist forces that are threat to the U.S., our citizens and our allies.

That said, Congress should nevertheless be wary of the modern presidency’s argument that it has a unilateral right to use the military to protect what it deems to be important national interests. Yet the Founders understood that the true brake on the decisions and ambitions of a commander-in-chief was less Congress’ formal power to declare war and more its power of the purse. Cutting off funds is a tried-and-true way to end a conflict or campaign that has lost the country’s favor. The fact this hasn’t been done regularly is more a sign of the members and American public being realistic about America’s global security concerns and commitments than a deep flaw in the constitutional order.

So it is time for Congress to clean out the closet when it comes to no longer relevant AUMFs and joint resolutions. But let’s be careful; not everything in that closet needs to go.

Gary Schmitt is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in the Program on Cultural, Social and Constitutional Studies.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.