In mid-December, peace talks between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) broke down after Rwandan President Paul Kagame elected not to attend an Angolan-brokered meeting with his Congolese counterpart Felix Tshisekedi. The talks were aimed at settling three years of violent insurgency in the eastern DRC—the most recent episode in more than 30 years of regional strife that has blended ethnic rivalry with a bid to control the area’s mineral wealth.

Since the breakdown in negotiations, the eastern DRC has devolved back into a war zone, with ongoing battles primarily fought between Congolese troops and the March 23 Movement (M23) militia backed by Rwanda and Uganda, further destabilizing Africa’s second largest nation by area. And while global attention has focused on the displacement of millions as a result of Sudan’s civil war, the DRC is experiencing an internal displacement crisis nearly as large, with 4.6 million displaced within the two provinces where the fighting is centered.

“Already dire humanitarian conditions are worsening rapidly, and access to these vulnerable populations is severely restricted by insecurity, roadblocks and the presence of violent armed actors,” said Eujin Byun, a spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in January. “Fighters are reportedly using people’s homes as shelters, endangering residents by blurring the distinction between combatants and civilians.”

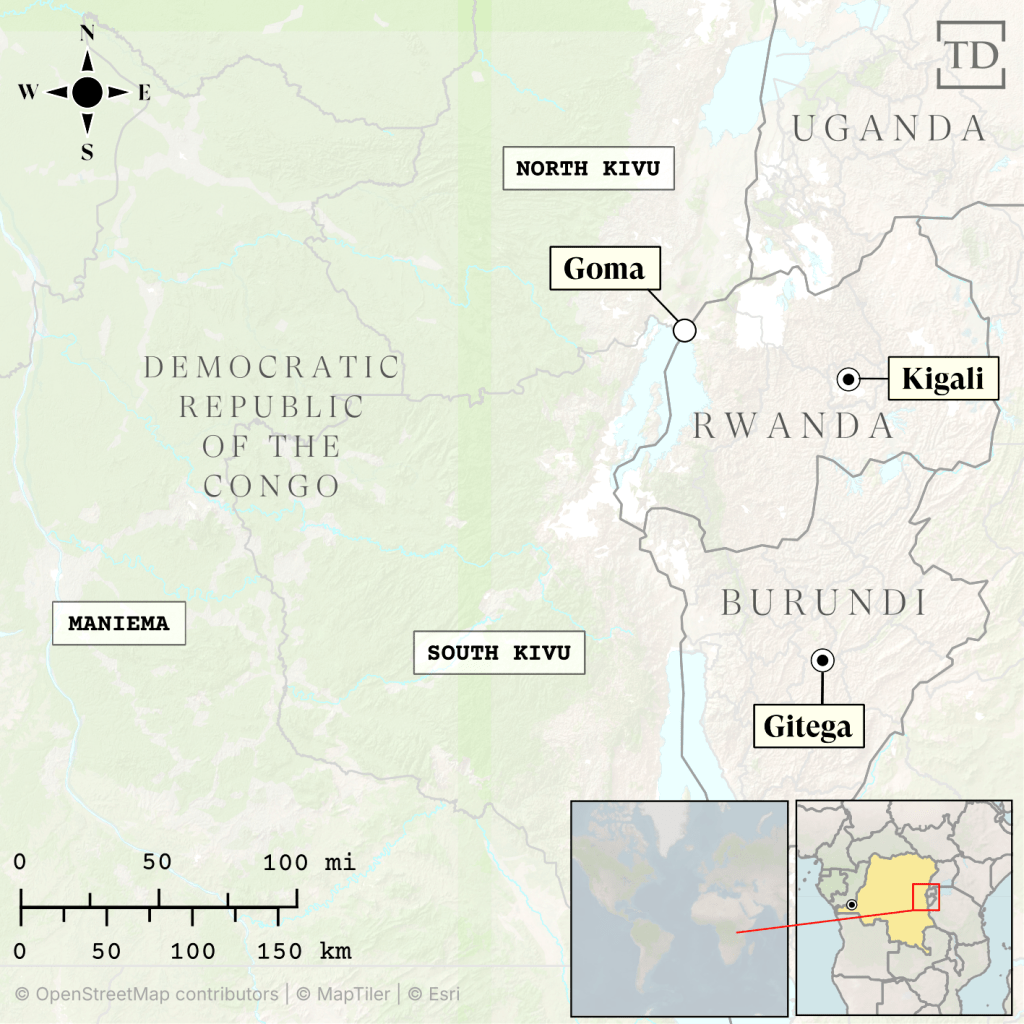

As of last week, M23 rebels had seized control of Goma, the largest city in the North Kivu province of the eastern DRC. As the fighting between the rebels and Congolese government forces continues amid M23’s march south, the AP has reported thousands fleeing the city and crossing the border into Rwanda, while others have celebrated the rebel victory. The African Union has condemned the recent hostilities and demanded M23 disarm.

Rwanda and its neighbors since the genocide.

The roots of the current conflict in the DRC can be traced directly to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, when radical members of the Hutu ethnic group attacked their Tutsi neighbors, killing an estimated 800,000 people in only 100 days. A narrative emerged a decade later: The conflict was contained, and it needed to be memorialized so that it was never repeated. The Kigali Genocide Memorial opened in 2004 in partnership with the U.K.’s National Holocaust Centre with the stated mission of preventing similar events from happening elsewhere.

The narrative housed in the Kigali Genocide Memorial was broadcast to international audiences in the Oscar-nominated film Hotel Rwanda, also released in 2004. Alongside the memorial, the film helped solidify in popular memory a definitive conclusion to the conflict and a firm association between Hutu and Tutsi identities and Rwanda’s national past.

Running counter to this story, however, is the fact that Hutu and Tutsi populations extend into neighboring countries, including the DRC, Uganda, and Burundi. This regional footprint meant that rather than concluding in July 1994, the ethnic tensions that fueled the genocide persisted into a broader regional war even after Rwanda secured peace domestically. Three decades on, what began as an ethnic conflict has grown into a longstanding regional war inflamed by the DRC’s poorly secured mineral wealth, which includes rare-earth minerals vital for manufacturing electronics.

During the Rwandan genocide and its immediate aftermath, some 2 million Hutus crossed the border into the eastern DRC. When Hutu extremists there began arming themselves, Congolese Tutsis followed suit, leading to waves of violent unrest. Rwanda and Uganda invaded the DRC twice to back the Tutsi rebels, resulting in two wars—first from 1996 to 1997 and again from 1998 to 2002. During the second of these conflicts, Rwanda looked to take control of the border region in the eastern DRC. Sometimes referred to as the African World War, it saw the death of between 3 million and 7 million people, making it among the deadliest conflicts of the 20th century.

Strategic interests.

The DRC’s eastern neighbors have strategic reasons for their interest in controlling larger parts of the region. The DRC is home to what the International Trade Administration estimates is tens of billions of dollars’ worth of mineral deposits, including gold, diamonds, cobalt, copper, and coltan. The latter is an ore of two rare-earth minerals that is an essential ingredient in electronics such as cell phones and laptop computers, and about 80 percent of the world’s coltan deposits are in the DRC.

“Rwanda has profited a lot from instability in the Congo,” explains Timothy Longman, professor of international relations and political science at Boston University and author of several works on Rwandan politics and society.

Longman points out that while Rwanda lacks its own mineral deposits, it is home to a coltan processing plant—the African continent’s first. Last spring, M23 took control of the Congolese mining town of Rubaya—and its large coltan mine—in the DRC’s North Kivu province, which borders Rwanda and Uganda, gaining authority over mining operations and mineral sales and taxation. A December 2024 U.N. report said the rebel group fraudulently exported at least 150 tons of coltan to Rwanda.

Rwanda has been the power behind the Tutsi-led M23 since its formation in 2012. A 2024 U.N. report found that the Rwanda Defence Force’s backing “extended beyond mere support for M23 operations to direct and decisive involvement.” The report also found that Ugandan military intelligence coordinated with M23 leaders.

This kind of interference in the DRC has not prevented Rwanda from getting Western support. Last February, the European Commission signed a mineral deal with Rwanda, prompting accusations that the African nation was working with Europeans to gain greater access to eastern Congolese resources. For Europe, the deal offered the hope of better competing with China for minerals used for electronics. Yet, the agreement came as M23 further extended its control over much of North Kivu.

A decade of M23.

M23’s recent military gains mark a resurgence of its violent power after nearly a decade of decline. The group emerged in 2012 out of a Tutsi mutiny from within the Congolese army. Soon after its founding, M23 gained significant control over North Kivu and its capital city of Goma, which sits on the Rwandan border. By the fall of 2013, some 100,000 people in North Kivu had been newly displaced from villages where their homes were looted and destroyed by rebels. Those numbers came in addition to the 2.6 million already internally displaced at the time.

To bring stability back to North Kivu, the United Nations deployed a rare offensive brigade, the U.N. Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO), to support the Congolese army against M23. By the end of 2013, M23 retreated from the eastern DRC’s urban centers but never fully dissolved, instead finding refuge in Uganda and Rwanda.

Three years ago, M23 began to rearm and regained control over parts of North Kivu, eventually cutting off Goma from the rest of the DRC. While Rwanda has previously denied involvement with M23, they responded to more recent accusations of collusion by arguing that the DRC government hasn’t taken steps to adequately protect its mineral-rich eastern provinces.

In a kind of tragic irony, Rwandan officials are making a similar point to Congolese civilians. While the Rwandan army has indiscriminately shelled camps for displaced people in Goma, the Congolese army has done little to quell the violence. Instead, military personnel have often exacerbated the situation by entering the camps and by launching artillery from nearby—actions that have effectively turned displaced people into human shields.

Muhesi Augustin, a professor of political science at the University of Goma and Catholic University of Graben in nearby Butembo, attributes the recent increase in violence to a fundamental failure of Congolese forces to maintain a presence in the region that secures it from the formation of internal and external rebel groups. In an email to The Dispatch, he explained that “[t]he crime currently observed in Goma, Butembo, and Beni is the result of the government’s weakness in imposing peace. In short, it is the weakness of the state which allows the perpetrators to benefit from insecurity in all forms.”

Heavy human toll.

Rose Tuombeane, an investigative journalist and leader of the women’s rights network Dynamics of Women for Good Governance, describes a dire situation in the eastern DRC. “Lives are being lost every day, the population is being decimated, businesses are in a coma, investments are collapsing, multinationals are closing their doors and leaving the country, unemployment is skyrocketing, and the population is terrorized,” she said via email.

Poor economic conditions have left millions of Congolese facing food insecurity, with farming and other means of food production disrupted or stolen by armed groups. These conditions have spurred a particular spike in sexual violence, as women, desperate to feed their children, attempt to get food in the surrounding bush, risking rape by embedded fighters—many of them members of the DRC military. The use of sexual violence as a military tactic by all combatants has been ongoing in the decades-long conflict in the DRC, earning the country a reputation as the “rape capital of the world.”

The conflict between M23 and government forces does not appear likely to resolve soon, despite the urging of regional African neighbors for Tshisekedi to meet with M23 leaders. Two weeks ago, Kagame described the Angolan-brokered December peace talks as a mere “photo op,” while DRC officials have continued to emphasize Angola’s importance to future negotiations. The degree to which reliable peace talks could address the internal weakness of the Congolese state in the east remains a critical question.

The situation was perhaps best described by Edgar Katembo Mateso, a Congolese university teacher who spoke to The Dispatch via email. Said Mateso: The area is “a permanent time bomb.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.