The Supreme Court’s recent affirmative action and student loan decisions have critics fuming, claiming the justices made themselves into a kind of super-legislature. Who are these robed figures to tell universities how to establish admissions criteria, or to deny struggling debtors some financial relief? But critics ignore the histories of both policies, which largely emerged through bureaucratic channels, without robust political debate or decisive majorities.

Affirmative action has its roots in the late 1960s, when President Lyndon Johnson wanted to further aid black Americans. Given the fiscal burdens imposed by earlier spending programs and the Vietnam War, his administration was looking for cheap alternatives. It eventually settled on a strategy to lean on businesses to hire more black workers and steer government contracts to minority firms, notwithstanding that congressional champions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had insisted that the law’s guarantees of equality would never result in preferential race-based hiring. Affirmative action thus got its start without any push from activists or legislators. President Richard Nixon later found affirmative action to be a convenient weapon against (white-dominated) construction unions. Though Nixon later changed his mind about affirmative action, by then the policy had momentum.

When racial preferences spread to school admission policies, judges upheld them despite consistent public opposition. In the 1978 case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, a splintered Supreme Court provided what became the one legally accepted rationale for affirmative action: that having a diverse student body would enhance the campus-wide educational experience. It was never clear why a student’s skin color per se was such an important factor in fostering diversity, but the legal consensus held. In the subsequent 2003 case Grutter v. Bollinger, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor affirmed the diversity rationale but also included a proviso that could hardly seem less legal: “We expect that 25 years from now the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today,” she wrote for the majority opinion. O’Connor was the last justice to have also been a legislator (serving two years in the Arizona Senate). In Grutter, she organized a coalition of justices around a rough-and-ready compromise more appropriate to the legislative arena.

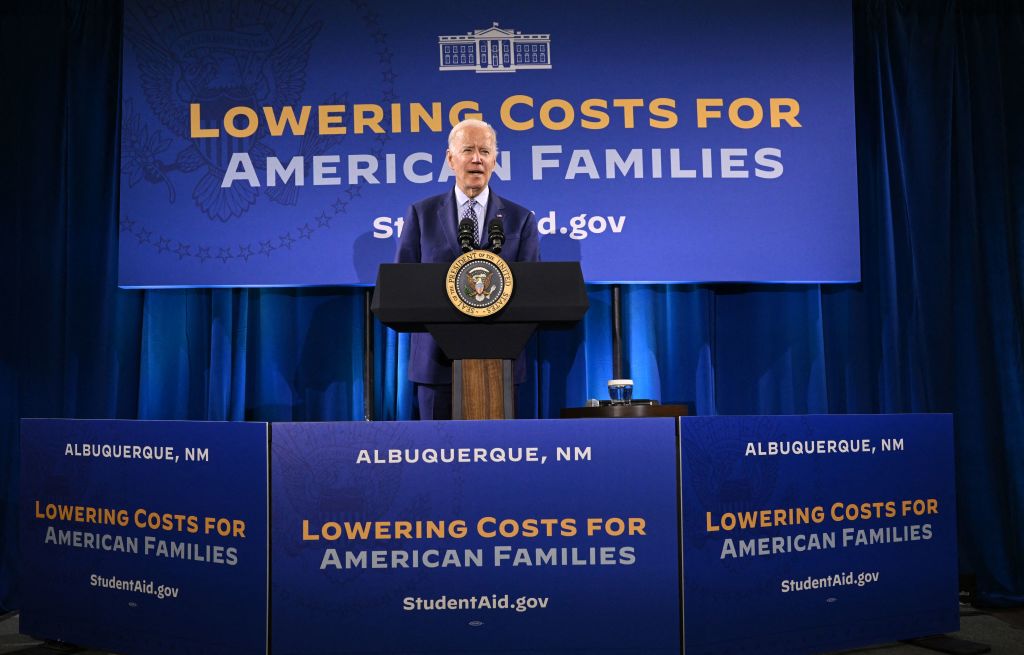

Five years ahead of schedule, a majority of Republican-appointed justices decided the Grutter compromise was built on self-deception and insisted that purely race-based affirmative action must end. President Joe Biden strongly objected. “We cannot let this decision be the last word,” he said, proposing instead that colleges should “take into account the adversity a student has overcome” as they select which students to admit.

Far from conflicting with the court’s ruling, Biden’s prescription is entirely consistent with it. Both the court’s majority opinion and Justice Clarence Thomas’ concurrence explicitly admit the good sense of such policies—so long as they genuinely consider applicants’ own experiences and accomplishments rather than simply judging them as bearers of a racial past. By eliminating some of the most glaring unfairnesses of the current system—for example, the fact that a privileged Hispanic student is advantaged over a low-income Asian one—a more individualized system would undoubtedly better comport with the American people’s preferences. If proponents of educational diversity rebuilt around lines other than skin color instead of lamenting a supposed legal setback, they would likely wind up with a fairer, more popular, and more politically durable program.

The history of Biden’s student loan forgiveness program is shorter, but reflects similar dysfunctions. In recent years, Congress has chosen to alter the terms of federal student loans on several occasions, instituting income-based repayment plans in 2007 and including various student loan relief provisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those changes passed with overwhelming bipartisan support. As recently as July 2021, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi insisted that Congress, not the president, would devise any debt forgiveness plan—a point she presumably made hoping to spur legislative action.

But Biden worried Congress wouldn’t allow the kind of loan forgiveness program he wanted to push. Rather than aiming to build another bipartisan coalition, he circumvented Congress in 2022 by invoking a provision of a 2003 statute passed in the wake of 9/11. That law said the secretary of education “may waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs … as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency.” Because COVID-19 remained a national emergency (at least as a matter of law), the Biden administration decided it could rewrite the terms of all federal student loans as it saw fit. The administration proposed an extremely generous program, which would have canceled up to $10,000 for individuals with six-figure annual incomes, or $20,000 for previous Pell Grant recipients. It estimated that 43 million borrowers would qualify, leading to a jaw-dropping estimated $430 billion in debt being discharged on the president’s say-so.

In striking this scheme down as an impermissible stretch of the original statute, the court last week explicitly rejected the idea that the president can cut Congress out of the loop whenever he finds doing so convenient. As Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “The question here is not whether something should be done; it is who has the authority to do it.”

It is especially galling that Biden dismissed the possibility of legislative action so lightly. Republicans had shown their willingness to support relief for student debt-holders during the pandemic. Many GOP legislators would almost certainly have supported some kind of targeted relief for people in near-poverty, even if they would have been very unlikely to entertain any scheme as indiscriminately generous as Biden’s. For good reason: Biden’s plan would have disproportionately benefited the already well-off, a fact which understandably rankled Americans who either already paid off their student loans or never took any out in the first place. If proponents of student loan relief tried to work through Congress’ political process rather than going around it, they might well succeed in devising a scheme that most Americans endorse as fair. But they would first have to try.

Many of the court’s critics act as if the conservative justices stole something from millions of Americans. They portray both race-based affirmative action and the promise of $10,000 of relief as akin to fundamental rights, something that (some) people have every reason to feel entitled to. But public policies that emerge from bureaucratic wrangling without clear support from legislators always remain vulnerable. This is the case even for a policy that managed to endure for decades, such as affirmative action, and it is especially true for maneuvers like the student loan forgiveness program, which were (if we are being honest) understood from the outset as opportunistic manipulations of existing statutes. The more durable and legitimate solution is simple: Do the work to pass legislation.

We should be especially skeptical of claims that congressional gridlock precludes legislative solutions. That sort of logic may sound hardheaded, but it is often deployed in self-serving ways by posturing activists and politicians. It is easy to write off “politics” as hopeless, but doing so risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. The job of our political leaders is to figure out what can actually earn the support of a legislative majority. It is hardly the end of democracy when our Supreme Court insists on that principle.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.