The word “unprecedented” will be doing a land-office business this week as Americans grapple with the implications of having a former president hauled into court on criminal charges.

Everybody seems to think that this is but the latest step toward becoming a banana republic, but we strongly disagree about who exactly is putting our Chiquitas in a bunch.

Is it Donald Trump, a leader of such low character that he tried to pay off a porno queen and of such incompetence that he couldn’t even do that right? Maybe his party, which has developed a moral flexibility that would make a porno queen blush?

Or is it Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, who is dumping kerosene on the fires of lunatic partisanship for a case that so far mystifies even his predecessor? Perhaps it’s Bragg’s party, which has become so choked with outrage over Trump’s capacity to escape its snares that it drives Democrats to riskier and riskier gambits?

There’s truth in all of that.

In the second decade of the 21st century, America faced new challenges while relying on an old, threadbare bipartisan consensus that had grown far too thin to constrain a rapacious demagogue like Trump. His assault on norms and traditions revealed two parties so weak that they could not put the national interest ahead of their members’ individual ambitions at crucial times, and so enthralled by negative partisanship that they could not cooperate to their mutual advantage. Now, the work of remediating those obvious problems is caught in the same blame-exploit-evade doom loop that helped cause them.

So the cry goes out for politicians who will break the cycle and lead us out of banana republic bondage and back to the promised land of a functioning constitutional democracy. But yearning for a new Moses is what got us here in the first place. The idea of Americanism is to govern ourselves, not to find charismatic leaders to govern us. Our worship of power and fixation on the office of the presidency is a big part of what broke the system.

We’re looking for a Moses, when we should be getting ourselves ready for a Grover.

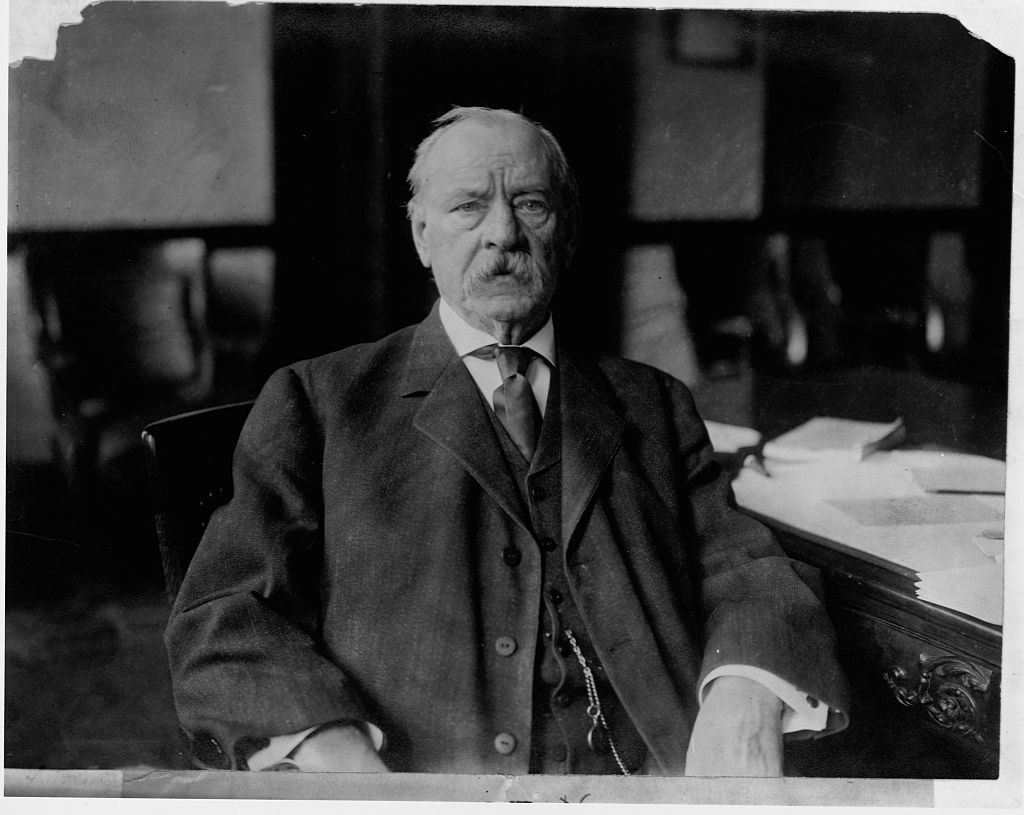

Grover Cleveland, the 22nd and 24th president of these United States, has been getting some attention lately because of Trump’s bid to be the first president who lost an election to come back and win a second term since Cleveland did it 131 years ago.

But rather than remembering the Buffalonian lawyer who went from mayor to governor to president in the span of three years for his non-consecutive terms, we ought to remember him for his courage, leadership, and devotion to American ideals .

If you remember anything about Cleveland from high school history class, other than his two appearances on the presidential timeline, it’s probably about the sex scandal that nearly cost him the 1884 election. Voters ultimately chose Democrat Cleveland and his private lapses over Republican James Blaine and his corruption-stained career. And thank goodness they did.

Debating who is underrated or overrated in history is a flaky biscuit of subjectiveness.

Are Abraham Lincoln and George Washington akshually overrated because they are so universally esteemed? Are James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson really underrated because nobody could really be as bad as history says they were?

But there is no doubt that Cleveland is among the most underappreciated presidents. Unsung by his own party, which was turning hard toward the progressive movement Cleveland fought, shunned by Republicans as being from the wrong team, and disdained by historians who always maintain a strong preference for active chief executives, the classically liberal, veto-loving Cleveland has had few champions.

Here to rescue Cleveland just when we need him so badly is author Troy Senik with a delightful and useful biography of the only Democrat elected to the White House in the 56-year span between Buchanan and Woodrow Wilson.

Senik’s book, A Man of Iron: The Turbulent Life and Improbable Presidency of Grover Cleveland, takes its title from a line by one of Cleveland’s few devotees. H.L. Mencken.

“His whole huge carcass seemed to be made of iron,” Mencken wrote of the man who became president when the Sage of Baltimore was a boy. “There was no give in him, no bounce, no softness. He sailed through American history like a steel ship loaded with monoliths of granite.”

Cleveland possessed few of the political gifts of most presidents who are deemed great. He was a drab speaker, a poor dealmaker, and spent little time or effort on “his legacy.” What he was, however, was incorruptible. At a time when Americans had lost faith in their leaders because of the behavior of men like Blaine and Gilded Age corruption, Cleveland set his hulking 275-pound frame against the wind.

Cleveland won the respect of voters who watched him willing to stand on the principles of the founding, even when it would have been to his personal advantage to bend. When members of his own party demanded more patronage, more spending, more activism, Cleveland refused: principles over partisanship.

While the story Senik tells of Cleveland the man is engrossing, perhaps more important is what the author tells us about the country that twice elected him.

Like some other great presidents, Cleveland rose to power in unlikely fashion. But unlike many who still generate worshipful biographies by the barrel, he did not use that moment to seek greater glory. He promised restraint, humility, and probity and stuck to it, even when loud voices demanded the kind of angry, populist leadership that would soon thereafter wreck the Democratic Party with William Jennings Bryan and eventually take America far away from its founding principles.

In a time of childish politics, Cleveland was a grown-up and showed voters the respect of treating them the same way. There are lots of men and women in American public life today who believe as he did that there is “political force in a moral idea,” but we are told that what voters really want is an avatar in the culture wars and vengeance against the other side.

That is true of many, as it was in the 1880s. But there were enough Americans then ready to honor courage and principle that they could hear difficult truths from Cleveland. Our capacity to escape our current banana republicanism will depend not on finding the right charismatic leader to tell us where to go, but on whether the electorate can develop the maturity to accept the hard work of self-governance.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.