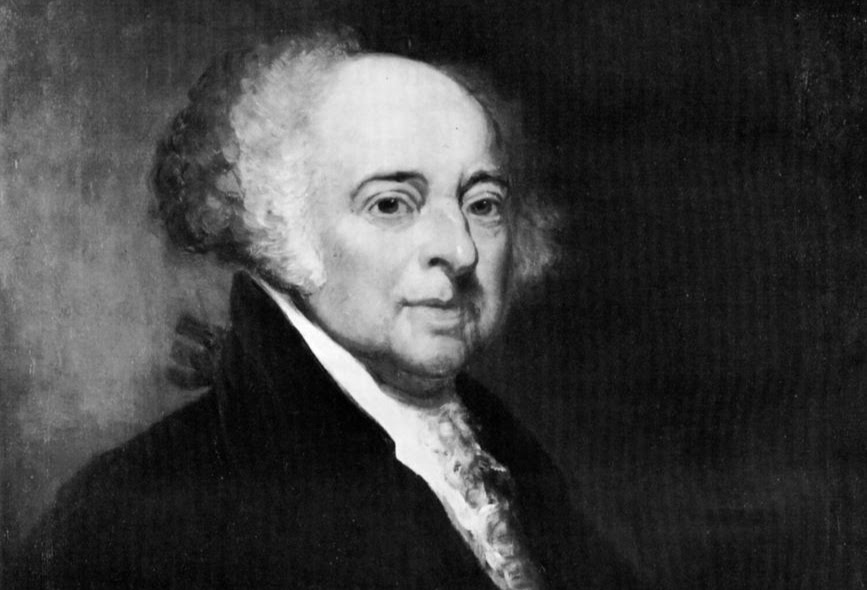

As regular readers will know, I admire Dwight Eisenhower for his modesty, moderation, and prudence. One of the ironies of our politics is that the American conservative movement that began in opposition to the New Deal really took off when the right identified Eisenhower and similarly accommodating Republicans as Public Enemy No. 1: “Our principles are round, and Eisenhower is square,” William F. Buckley Jr. declared. Eisenhower accepted the New Deal as a fait accompli, and the postwar right would not. Ironically, they found their champion in Ronald Reagan, who idolized Franklin Roosevelt and habitually described himself as a New Deal Democrat estranged from his party by its radicalism in the 1960s. But if Republicans are looking for a president to emulate in these trying times, the first man to turn to is neither Eisenhower nor Reagan nor the sainted Abraham Lincoln but the chief executive who, in my mind, has a very strong claim on being the founding father of American conservatism: John Adams.

Some of you will be familiar with a few lines from Adams’ letter to John Taylor dated December 17, 1814. Adams, by then a former president—a one-termer who appeared to many of his contemporaries to be a political failure—has some harsh words for democracy: “I do not say that Democracy has been more pernicious, on the whole, and in the long run, than Monarchy or Aristocracy. Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as Aristocracy or Monarchy. But while it lasts it is more bloody than either. … There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide.”

My friends and colleagues Jonah Goldberg and Nick Catoggio have been on a very amusing tear about the baleful influence of small-dollar donors on our politics. Nick writes that we don’t really have a small-donor problem as much as we have an internet problem, and there is something to that. But the fundamental problem is the one that commanded so much of Adams’ attention more than two centuries ago, what he and the men of his generation called “passion,” and its twin, “enthusiasm.”

It is worth reading the rest of the Adams letter rather than attending only to its most famous lines. The epistle in its entirety should be taught in our history and civics classes.

Adams earlier had complained to Taylor that one could publish a vast martyrology of the good and great men destroyed by the passions of the masses. Taylor replied that it would be easy enough to turn the equation around—think of all the common people slain by the vanity, greed, or stupidity of the supposedly great men who ruled over them. Adams wasn’t having it, and wrote in the famous letter: “We curse religiously the Memory of Mary for burning good Men in Smithfield, when if England had been democratical She would have burned many more.” Adams’ full answer is wise and useful, even if unhappily punctuated by the familiar bigotry (the word antisemitism had not yet been coined) of his age:

You Say I “might have exhibited millions of Plebians, sacrificed to the pride Folly and Ambition of Monarchy and Aristocracy.” This is very true. And I might have exhibited as many millions of Plebians sacrificed by the Pride Folly and Ambition of their fellow Plebians and their own, in proportion to the extent and duration of their power. Remember Democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy Yet, that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to Say that Democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious or less avaricious than Aristocracy or Monarchy. It is not true in Fact and no where appears in history. Those Passions are the same in all Men under all forms of Simple Government, and when unchecked, produce the same Effects of Fraud Violence and Cruelty. When clear Prospects are opened before Vanity, Pride, Avarice or Ambition, for their easy gratification, it is hard for the most considerate Phylosophers and the most conscientious Moralists to resist the temptation. Individuals have conquered themselves, Nations and large Bodies of Men, never.

When Solons Ballance was destroyed, by Aristides, and the Preponderance given to the Multitude for which he was rewarded with the Title of Just when he ought to have been punished with the Ostracism; the Athenians grew more and more Warlike in proportion as the Commonwealth became more democratic. I need not enumerate to you, the foolish Wars into which the People forced their wisest Men and ablest Generals against their own Judgments, by which the State was finally ruined, and Phillip and Alexander, became their Masters.

In proportion as the Ballance, imperfect and unskillfull as it was originally here as in Athens, inclined more and more to the Dominatio Plebis; the Carthaginians became more and more restless, impatient enterprising, ambitious avaricious and rash; till Hanibal swore eternal <, Enmity to the Romans, and the Romans were compelled to pronounce Delenda est Carthago.

What can I Say of The Democracy of France? I dare not write what I think and what I know. Were Brissot, Condorcet, Danton Robespiere and Monsiegnieur Equality less ambitious than Cæsar, Alexander or Napoleon? Were Dumourier, Pichegru, Moreau, less Generals, less Conquerors, or in the End less fortunate than [he] was.? What was the Ambition of this Democracy.? Nothing less than to propagate itself, it is Principles its System through the World, to decapitate all the Kings, destroy all the Nobles and Priests in Europe? And who were the Instruments employed by the Mountebanks behind the Scene, to accomplish these Sublime purposes? The Fisherwomen, the Badauds, the Stage Players, the Atheists, the Deists, the Scribblers for any cause at three Livres a day, the Jews, and, Oh! that I could erace from my memory! the learned Divines profound students in the Prophecies. Real Philosophers, and Sincere Christians in amazing Numbers over all Europe and America were hurried away by the torrent of contagious Enthusiasm. Democracy is chargeable with all the blood that has been spilled for five and twenty years. Napoleon and all his Generals were but Creatures of Democracy as really as Rienzi Theodore, Mazzianello, Jack Cade or Wat Tyler. This democratical, Hurricane, Inundation, Earthquake, Pestilence call it which you will, at last arroused and alarmed all the World and produced a Combination unexampled, to prevent its further Progress.

Americans get a little psychic jolt out of writing, with capitalization, “We the People,” but political philosophy has recognized that we the people are the main problem going all the way back to the beginning. It is scandalous to frankly admit this in our times: The prehistoric truth is forbidden by postmodern manners. But Plato understood it, Hobbes understood it, Confucius understood it—and our Founding Fathers understood it, too. Plato, Hobbes, Confucius, and many of the other giants of political philosophy understood, each in his own way, that there is no such thing as We the People, that there are groups and factions and classes and interests, with desires and priorities that are, at least at the margins, mutually exclusive, and that the role of the state is to seek harmony and balance among these rivals not by arriving at a state of perfect mutual satisfaction but by convincing (or, more often, forcing) the parties to accept imperfect, second-best, compromise settlements that satisfy no one entirely but provide for the best opportunity of overall flourishing. At one point, that was elementary stuff, Statesmanship 101, as obvious to John Adams as it would have been to Cosimo de’ Medici or to Marcus Aurelius. Adams was obliged to take his Congress more seriously than Cosimo did his signoria or Marcus his senate, but all of them understood that there was more to good governance than deferring to the tribunes of the plebs or treating the state and/or its chief executive as the embodiment of the will of the people as a whole. Marcus Aurelius was an emperor, but he was less of an imperialist than some of our democrats in good standing.

Liberty under a constitutional order is an idea that was born in England and grew up in the United States. In a recent conversation with our friend Dan Hannan (who sits in the House of Lords as Lord Hannan of Kingsclere), Jonah describes democracy not as some sanctifying romantic principle that will necessarily lead to a noble society in which the state is an authentic representative of the people but simply as a “hedge”—a hedge against all of the horrifying things that people do when you give them political power without checks and accountability. That’s the real conservative sensibility at work: If progressivism is about making incremental improvements in the direction of utopia, conservatism is about avoiding catastrophe. And if democracy is a hedge against Caesarism, constitutionalism is a hedge against democracy—against the horrifying things that the people will do when you give them political power without checks and accountability. The loyalist clergyman Mather Byles put the question to his fellow Americans on the eve of the revolution: “Which is better—to be ruled by one tyrant three thousand miles away or by three thousand tyrants one mile away?” That is a fair question. Adams himself was skeptical about independence in the years leading up to the revolution. The American constitutional order is an attempt to provide an option other than the choice between one tyrant and 3,000—or, in our time, 320 million—of them.

The peculiar and narrow effects of small-dollar donations and social media are very much of our time and place, but the underlying issue isn’t—and the solution, to the extent that there is one, isn’t something we have to dream up de novo. We have been here before—that is how we got here in the first place. A liberal constitutional order works by dividing up power among competing factions and institutions, setting them against one another and, when necessary, frustrating the will of We the People when it congeals into a temporary majority in support of some destructive policy or project. What will save our system is . . . everything populists left and right are working against, everything a good populist hates with all his heart and both his lungs: not the destruction of the power of political parties and their leaders, but the reinvigoration of those parties and the restoration of their traditional role as gatekeepers; fewer open primaries and more smoke-filled rooms; not the democratizing of anti-democratic institutions such as the Electoral College and the Bill of Rights, but the fortification of these institutions and an unembarrassed emphasis on their countermajoritarian character; more federalism rather than more nationalism; better and more effective news media gatekeeping rather than the ever-finer subdivision of the national conversation; more independent power exercised by interest groups rather than less; less regulating and more legislating, meaning a constrained executive branch and a more active legislative branch; more textualism and less opportunism in constitutional disputes; less crusading and more compromising; government and elections that are boring rather than a national pastime.

And if that means throwing a few more bucks into the collection plate at church rather than heaping those greenbacks into the digital coffers of political campaigns, then we will have rediscovered a venue in which small-dollar donations do a lot of good.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.