Over the last year, Kentucky Secretary of State Michael Adams has become used to receiving images of nooses and threatening voicemails. One threat was serious enough he reported it to the FBI.

“It’s not just me,” he said. “It’s the state board of elections. It’s my senior staff.”

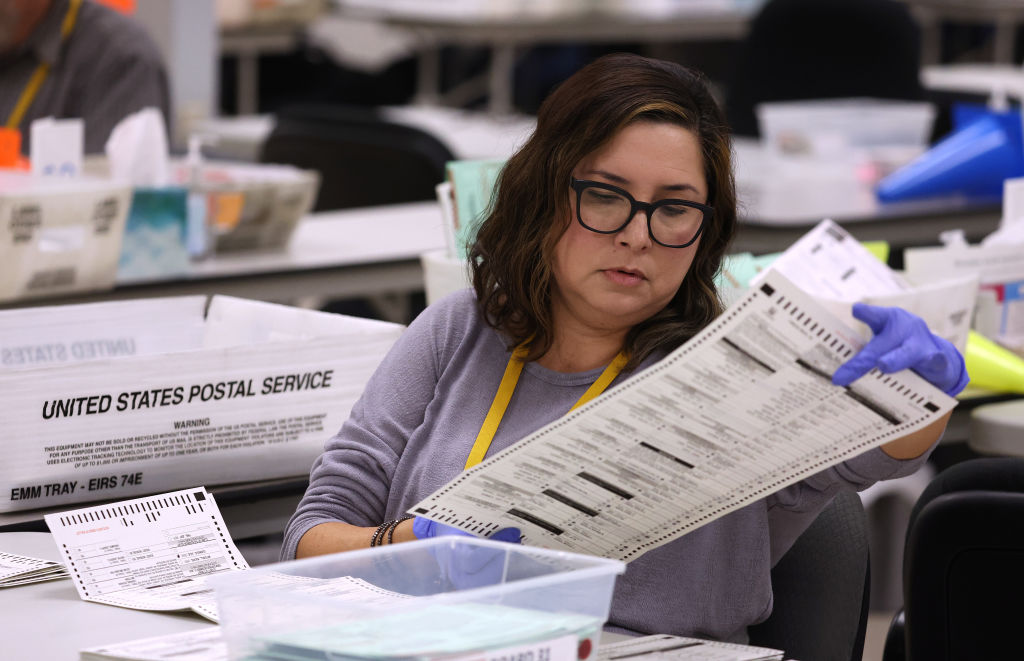

Prominent politicians and conspiracy theorists have spent two years trumpeting lies about the 2020 election and have already begun sowing seeds of doubt about Tuesday’s high-stakes midterms. State and local election officials are bracing for a tumultuous few weeks.

Kenneth Polite Jr., assistant attorney general for the Department of Justice’s Criminal Division, said in August that the DOJ has received more than 1,000 tips about election workers facing threats since last summer. About 11 percent of those tips led to the FBI opening investigations, and nearly 60 percent of the potentially criminal threats were in states subject to 2020 election lawsuits, recounts, and audits: Arizona, Georgia, Colorado, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Wisconsin.

Last month, an Iowa man was arrested for allegedly threatening Arizona election officials. “You’re gonna die … we’re going to hang you,” authorities allege the man said in a 2021 voicemail for a Maricopa County Board of Supervisors election official. “Do your job … or you will hang … we will see to it. Torches and pitchforks. That’s your future,” he allegedly told other Arizona officials weeks later.

Bill Gates, chairman of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, told reporters Thursday during a briefing hosted by the Center for Election Innovation & Research that his department has seen an uptick in harassment of poll workers during the primaries. “There’s still people spreading misinformation, just last week, about what our employees did in the 2020 election,” Gates said. “And guess what, those employees called out by name on social media are getting some of the most vile threats, threatening emails, etc. … and this is while everyone is trying to run an election.”

In Pennsylvania, a Department of State spokesperson told Axios that threats its workers get are “anonymous, often cryptic,” implying “that election officials are being watched.”

“You kind of worry when you go out,” said Melanie Ostrander, elections director in Pennsylvania’s Washington County.

Fueling the threats are GOP politicians and candidates who have embraced election conspiracies as platform planks, from gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake and secretary of state candidate Mark Finchem in Arizona, to gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano in Pennsylvania, to secretary of state candidate Kristina Karamo in Michigan.

Only a minority of voters overall believe President Joe Biden’s electoral victory was fraudulent, but the “big lie” has moved into the mainstream among Republicans: Monmouth University found in September that six in 10 Republicans believe Biden “only won due to voter fraud.”

It’s little wonder, then, that the number of Republicans who distrust election administration in general has grown in recent years. In 2018, 87 percent of Republicans told Pew Research Center that they trusted the election would be administered well. That figure has since dropped to 56 percent.

“Just think about the statement, if we win, we win. If you lose, it was stolen,” said Ryan Burge, a political science professor at Eastern Illinois University. “It puts all the secretaries of state’s offices and the election workers and the poll workers in a terrible spot. Because it’s essentially telling them, ‘Deliver me the election, or I’m gonna say you’re a liar.’”

That’s already happening in some places. In September, My Pillow CEO Mike Lindell—a prominent election fraud conspiracy theorist—encouraged supporters in a YouTube video to “bombard” Michael Adams’ office with records requests following a Kentucky state senate candidate’s failed attempts to overturn election results. Lindell’s followers did as they were asked—but they weren’t sure why. “We’ll contact them and ask them, ‘What is it you want us to give you?’” Adams said. “And they’ll say, ‘I don’t know. I just did this because the Pillow guy told me to do it.’”

All these new pressures are taking a toll, causing fed up election workers in some states to quit. In a survey released in March, the Brennan Center for Justice found that nearly one in three election officials knew at least one worker who had left the field in part because of safety concerns. One in six election officials said they had personally experienced threats as well.

“Election officials are retiring, resigning. They don’t want to be subjected to the harassment that they’re getting. And the concern is, who replaces these people?” Michael McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida, told The Dispatch. “In some of these very rural places, it may be that there’s no one.”

Adams said that in 2020—which he described as a “hellish year” for election officials due to the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic—only two of Kentucky’s 120 county clerks quit. But he said nine county clerks have already left this year, and another 14 have chosen not to run again. “That’s a high attrition rate,” Adams noted. “It’s very unusual. So clearly this has taken an emotional toll.”

The threats haven’t stopped Adams from doing his job, “but it’s the kind of thing you think about at the back of your head when you’re walking to your car at night and it’s dark.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.