As rumblings of an impending global recession have grown over the past several weeks, many have pointed to plummeting copper prices as a harbinger of economic doom. These fears stem from copper’s role as an economic bellwether: dropping copper prices are often thought to portend grim economic prospects. But experts aren’t sure just how much copper deserves that distinction.

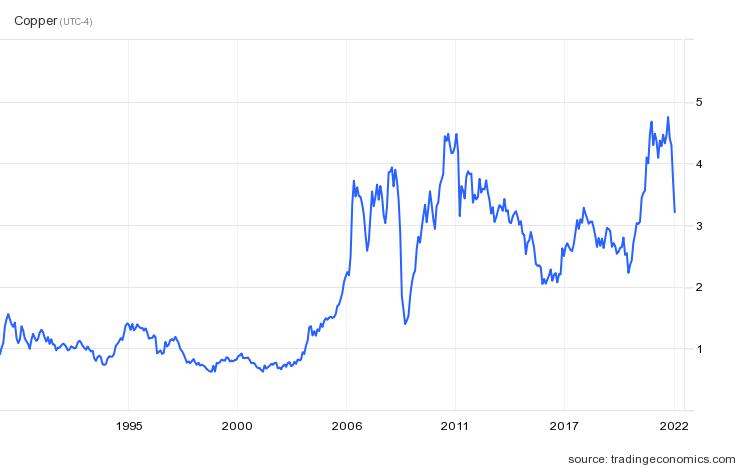

Copper, which is down 29 percent from its March 4 high earlier this year, is considered a bellwether because of its many uses. Electric appliances, industrial engines and machines, cars and transportation, communications networks, and plumbing and electricity in homes and commercial buildings all have copper as an essential component.

“When you have a slowdown in industrial production, you have a slowdown in the copper price,” Carlos Risopatron, director of economics and environment at the International Copper Study Group, told The Dispatch.

Slumping copper prices may suggest that demand for copper is also falling. That could translate to decreased production across the wide range of products and industries that rely on copper.

Conversely, when investors expect a growing economy, copper is needed for all the additional construction and manufacturing, driving up copper prices—or so goes the theory.

The economy is entering a period of uncertainty, said Colorado School of Mines economist Roderick Eggert.

“So a household postpones its purchase of a car that contains a lot of copper,” he said. “Or maybe builders postpone the construction of new homes, which contain copper. And maybe companies in the manufacturing sector postpone investment into production capacity, until the period of uncertainty is resolved.”

Still, copper’s track record as an economic predictor is mixed.

Copper has entered a bear market—typically defined as a market where prices have fallen 20 percent from a recent high over at least two months—before each of the last 30 years’ recessions, Markets Insider observes. But not every drop in copper prices directly preceded a recession.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson famously remarked that the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions. A similar point could be made about copper markets.

For example, bear markets in 1996 and 2011 didn’t precede recessions. And as copper prices declined over most of the 2010s, in part due to copper overproduction, the U.S. economy steadily grew.

“It’s 50-50, basically,” said John LaForge, who has written about copper’s predictiveness as the head of real asset strategy at Wells Fargo Investment Institute. “There are lots of things that can help you predict a recession, and copper can help, but it’s not perfect.”

Mark Hulbert, a writer at MarketWatch, calculated the correlation between the performance of copper prices and the S&P 500’s subsequent performance. If copper is a reliable bellwether of the economy, we would expect that correlation to be positive—soaring copper prices herald a strong economy and plummeting copper prices a struggling one.

But Hulbert found that over the last 30 years, the correlation has been unsteady, and for the most part negative.

According to Risopatron, copper’s price fluctuation is a result of speculators’ reactions to other market factors, like interest rates and the strength of currencies—factors that are themselves a reaction to fears of recession.

Factors internal to the copper industry, like strikes at mines and production facilities, can also impact the price of copper, independent of the condition of the broader economy.

In 2017, workers at the world’s largest copper mine, Escondida in Chile, went on strike for 44 days. “Obviously, there was a jump in the copper price that was not correlated with global industrial production or with the global GDP,” said Risopatron.

Demand-side factors can also impact copper’s price. LaForge pointed to the fact that China, the world’s largest consumer of copper, has “been going through these fits and starts with their economy,” which acts as an additional force weighing down the price of copper.

While the price of copper is not a foolproof predictor of recessions in general, this particular decline in copper prices could still precede one. Richard Kelly of the investment bank TD Securities warns that the likelihood of a recession in the next 18 months is greater than 50 percent—an estimate that doesn’t rely on copper’s supposedly predictive power.

According to Luke Danielson, president of Sustainable Development Strategies Group, copper will only grow in its usefulness as the world transitions to cleaner power.

“Copper is really vital to a better future,” Danielson told The Dispatch. Highly energy-efficient motors, for example, require large amounts of copper, as does solar energy, which requires an average of 10 tons of copper per megawatt of energy produced.

He added that more than 700 million people do not have access to electricity. “People need electricity to be participants in the modern world,” and electrifying these areas will require extensive amounts of copper.

“The transition to cleaner energy technologies almost certainly will increase the demand for copper,” said Eggert. “As the energy economy relies increasingly on electricity and electrification, that will, in a broader sense, increase demand for copper.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.