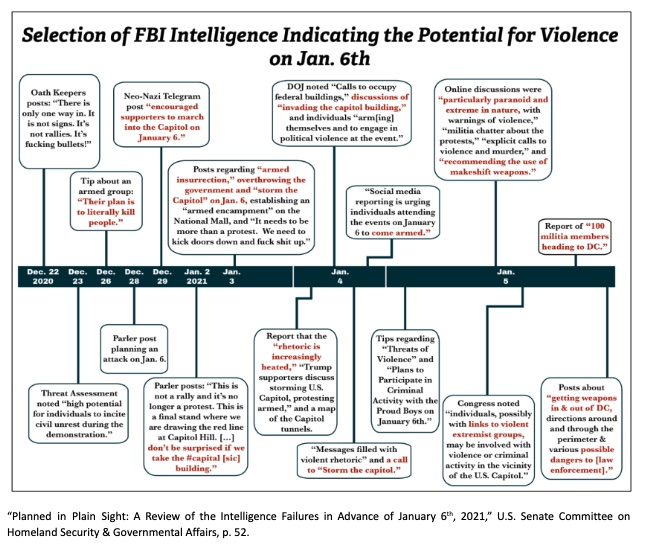

Late last month, the majority staff of the Senate’s Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee issued a 106-page report on the intelligence failures leading up to the January 6 “surprise” attack on the U.S. Capitol. Reading through the report, one can’t help but be gobsmacked by the amount of available, open-source information officials had about Trump supporters coming to Washington armed and threatening violence. Nor was there a shortage of online discussion and tips about attendees directing their ire toward the Capitol, Congress, and the final tallying of the Electoral College votes.

Nevertheless, neither the FBI nor the intelligence arm of the Department of Homeland Security assessed that there was a “credible” threat of civil disobedience, let alone actual violence. There were no official warnings given to the police and security officials responsible for protecting the Capitol or congressional proceedings.

Why the failure?

The FBI’s answer has been that it did not have a single credible source offering knowledge of such a plan. As one senior bureau agent testified to the January 6 Select Committee: Sure, “there was some rhetoric out there that we should, you know, storm the Capitol, but it wasn’t like, ‘let’s go storm the Capitol, we are going to storm the Capitol.’” Without evidence of a specific plan, the FBI believed it was precluded from further investigating these multitude of online boasts because they were protected free speech.

The report argues, however, that this was too narrow an approach, both analytically and bureaucratically.

First, the committee staff concludes that the bureau failed to adequately consider the totality of threats appearing on social media. (The FBI was looking for hard evidence that someone was planning to light a match, while not taking into account all the folks who were piling up straw.) Second, based on prior rallies in November and December 2020, officials were focused on possible violence breaking out between groups like the Proud Boys and Antifa. Third, the FBI failed to tabulate and pass along all the material it had collected by conflating what it was legally allowed to do with it with the higher evidentiary bar for opening up more intrusive investigative techniques. In the parlance of the Attorney General Guidelines—guidelines intended to set the internal rules for FBI operations and investigations—officials had the authority to make an “assessment” about what they were seeing and to pass that assessment along to the other relevant security and police entities even if they were not ready to undertake an actual criminal investigation.

More broadly, as the report notes, the bureau looks at these postings through the lens of the First Amendment case Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), which struck down an Ohio law that had made it a crime to advocate for “crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform.” Advocacy is not enough. What matters is whether the speech is “directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and is “likely to incite or produce such action.” To determine that, the FBI looks to see how specific a threat is, the capability of the person or group to carry out that threat and, in turn, evidence of coordination within a group. With these criteria in mind, online “boasting” is then readily dismissed as chest-thumping hyperbole.

As late as January 3, 2021, and with all the previous information flowing in about possible violence, the FBI’s Washington Field Office flatly stated in internal emails that it did “not have any information to suggest these events will involve anything other than protected activity.” In the aftermath of 9/11, reforms were made to make the intelligence arm of the FBI less likely to see the threat from international terrorism from the perspective of its traditional role as a crime-fighting organization and, hence, more likely to jump on leads that lacked the specificity of “imminent lawless action.” But the events of 1/6 suggest that, when it comes to domestic threats, it still acts like the bureau of old, waiting for unequivocal evidence that a crime is about ready to take place. And in this instance, ignoring the fact that it could under its own rule circulate an assessment taking account of all the threatening language it and others were seeing.

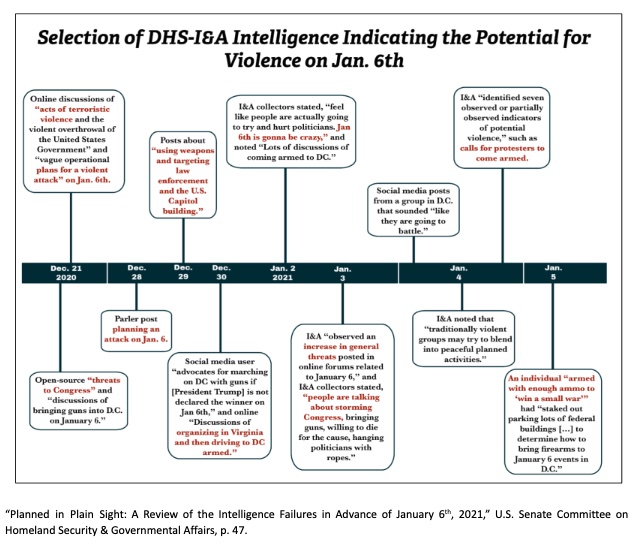

As for the intelligence arm of DHS, the analysts monitoring open-sources put down the would-be threats as not credible—again, as hyperbole. And like the FBI and the Justice Department, they were focused on possible violence between election protesters and their opposites. Moreover, according to its own postmortem by the agency’s inspector general, DHS was in the process of expanding its open-source collection efforts in the months before January 6. It hired a considerable number of entry-level analysts who, in retrospect, were not adequately trained. Like the bureau’s analysts, they were seemingly unaware of the fact that, short of identifying a specific credible threat, they could still compile and circulate the unconfirmed threats they were seeing online.

But this failure on the part of DHS analysts was not simply a case of inexperience. Mentioned in the report, and based on earlier reviews by the GAO and DHS’s inspector general, DHS had grown wary of collecting and reporting on matters that could be seen as politically sensitive. The DHS had gotten hammered the year before for reporting on individuals involved in the post-George Floyd protests in Portland and a few journalists covering the violence there. The “chilling effect” was real. Given the heated politics surrounding the 2020 election, it’s no surprise that DHS, which was still under the leadership of Trump-appointed officials, would hesitate to put out threat warnings about a Trump rally.

Although the FBI and DHS could have (and should have) done more with the intelligence they had, both had been affected by the back-and-forth over how forward-leaning we want these agencies to be in collecting intelligence domestically and bumping into rights of privacy, free speech, and association. Depending on what side of the fence you’re sitting on politically, and what the issue of the day is, you’ll find editorial writers, commentators, and elected officials complaining about overreach. It’s easy to say that established guidelines should direct how these intelligence elements should go about their jobs but, from a bureaucratic point of view, it’s no surprise that folks want to play it safe. Again, this is not to excuse the bureau or DHS for failing to do more to flag the threat to the Capitol on January 6; rather, it’s just to point out that these agencies operate in a political setting that they don’t make.

Finally, there is an assumption in the report’s analysis that, ultimately, the assault on the Capitol could have been avoided if the intelligence arms of the bureau and DHS had done their jobs adequately. Alerted sufficiently, the argument goes, the Capitol Police, the District Police, and the various federal security elements would have been prepared for the onslaught that took place.

But when something like January 6 happens, it’s a bit too easy to say “intelligence failure,” thereby shifting the blame to intelligence community elements. The staff report dismisses too summarily former Acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen’s suggestion that you didn’t need a specific intelligence threat assessment to know that there was considerable potential for violence, and that it would be aimed at the Capitol: “the risk of violence,” he is quoted as saying, was “almost common sense.” There had been two pro-Trump rallies in November and December, but the January 6 “Stop the Steal” rally was going to be of a different order: larger, with Trump speaking to the crowd, and an actual target for the thousands to direct their anger at—the Electoral College count in the Capitol.

It’s true that the events of January 6 were unprecedented and, hence, by their very nature more difficult to predict. But that doesn’t mean they could not have been prepared for. Too often “intelligence” has become a crutch for American policymakers and officials to avoid thinking through what might happen and, in turn, what needs to be done. Waiting for a “no-doubt, here’s what is going to happen,” intelligence report can be an excuse for not using one’s own experience and, yes, common sense assessment of what might be possible. Given the history of intelligence failures, one would think that officials and policymakers, while hoping for the best intelligence, would not depend on it for taking action. In short, there are failures in intelligence—as the report spells out—but there are also failures to use one’s own intelligence that should not be ignored as well.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.