Augustus boasted that he had found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble: “Marmoream relinquo, quam latericiam accepi.” That doesn’t really seem to be true, historically, though the opening of the marble quarries at Carrara did provide the new emperor with raw materials for some new construction and a few upgrades. Rome’s transformation wasn’t architectural but political: from Octavian to Augustus, from republic to empire, from conservative restraint to imperial grandiosity.

The way things went, the Romans would have been better off with their sturdy city of brick.

Two days in Washington, D.C., our own imperial city of marble, is enough to remind me how much I dislike this place.

Washington has its share of urban problems, though from the street level it feels a lot more squared-away than the typical major U.S. city. It remains in the top 25 when it comes to rates of violent crime, but its murders per capita run about one-quarter of what they suffer in St. Louis, less than half what they endure in Baton Rouge, and just over half of what they have to put up with in Kansas City. It has a high rate of homelessness and a very visible vagrancy problem, though not quite what one sees in Los Angeles or New York City. Its public spaces feel relatively—relatively!—orderly and tidy compared to most other big cities in the United States. Going by undergraduate and advanced degrees, Washington is one of the most highly educated cities in the country; household incomes are half-again as much here as in Jacksonville or Phoenix.

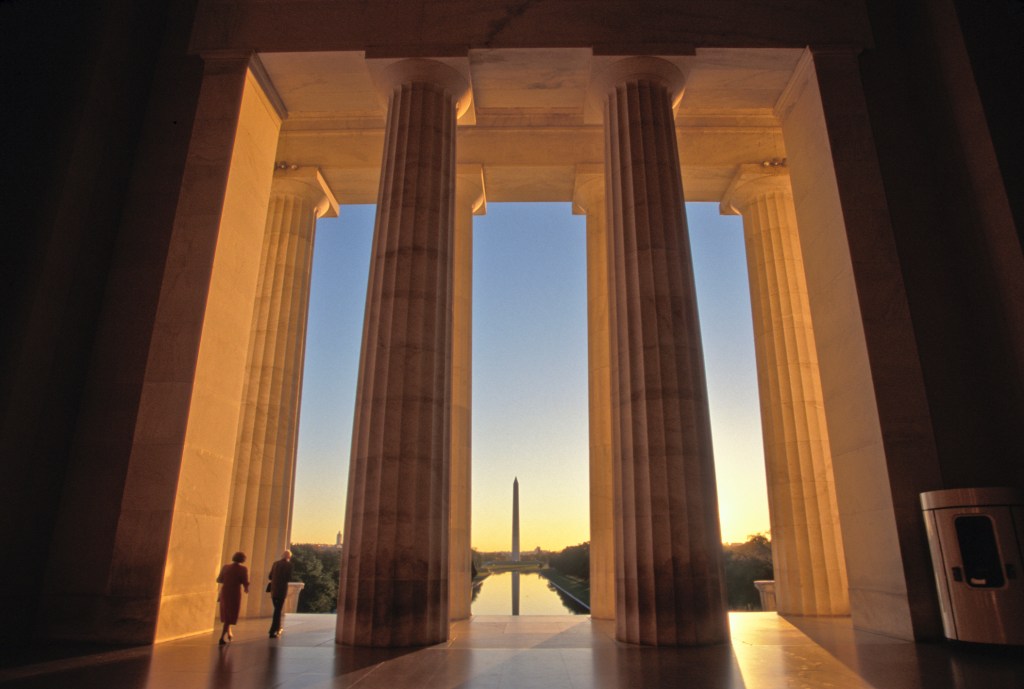

What I find objectionable about Washington is the thing that brings so many tourists here every year: all that marble. Not the marble itself, of course, but what it stands for, which is, in Washington, the same thing it was in Augustan Rome: the worship of power.

There is something genuinely bizarre about our capital city. From the pilgrims to the Founding Fathers, Americans often thought of themselves in Old Testament terms, as new Israelites building a new Jerusalem, that inescapable “shining city on a hill” of American political rhetoric. And what looms over Washington? Egypt, in the form of a gigantic obelisk erected to the memory of the man after whom the city is named. But, then, Washington isn’t really named after George Washington, the man—it is named after Washington, the god-man, who is depicted in the company of Roman deities (Minerva, Vulcan, Ceres), swathed in the purple of a Roman imperator, seated on a throne, sword in one hand, the other hand making a gesture of command. The divine attendant at his left hand blows a triumphal trumpet, the one at his right hand bears a fasces. The scene is titled, appropriately enough, The Apotheosis of Washington.

That work, found on the inside of the Capitol dome, was painted by Constantino Brumidi, whose previous clients had been the Vatican and Pope Gregory XVI, a fact that surely would have scandalized the Puritans, whose horror of the pomp and what they judged to be idolatry in Catholic and Catholic-adjacent religion was so intense that they had passed a law calling for the execution of any Jesuit who sneaked into Massachusetts. Somewhere between the modest New England meetinghouse and the thoroughly pagan Greco-Roman temples and monuments of Washington, something went wrong—from brick to marble.

Architecture isn’t a mode of ideology, but it does capture and express a sensibility. When autocratic nationalists in the early 20th century took up the fasces as their symbol (giving us the word fascism), they looked back to Augustan models even as they were giddy with the potentialities of a modern technological age that was just coming into its own. The Italian Futurists at times seemed to be interested in only two things: airplanes and misogyny—both of which, they imagined, were related to strength. Strength, in the fascist mind, solves all problems—it is not for nothing that our “new right” in the United States is at least as interested in weightlifting and a particularly cartoonish, cage-fighting form of performative masculinity as it is in any political idea. To make power visible is fundamental to the fascist aesthetic, and the fascist aesthetic has never been restricted to fascists per se: Paul Phillipe Cret gave Washington the Eccles Building in 1937, while the capital city was under the spell of Franklin Roosevelt, who had difficulty containing his desire to gush about that “admirable Italian gentleman,” Benito Mussolini. The Eccles Building, which houses the Federal Reserve, would have been right at home in the Berlin imagined by Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer: one part Roman Empire, one part Golden Age of Flight.

As American sensibilities grew uglier, so did Washington. The FBI headquarters is very possibly the ugliest public building in these United States—it hardly looks like it belongs to the same civilization as, say, Philadelphia’s City Hall, and, in some important sense, it doesn’t. Frank Gehry’s Eisenhower Memorial is perplexingly disconnected to its subject and its times; the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., arguably the most significant Christian minister in American history, is memorialized in a Soviet brutalist (Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin’s earlier subjects had included Mao Zedong) relief reminiscent of such works as the Monument of the Bulgarian-Soviet Friendship.

It is not as though we have forgotten how to make monuments—Glenna Goodacre’s Vietnam Women’s Memorial was a product of the 1990s—but we have committed ourselves to another kind of public life, another style of political life.

Washington’s style is not limited to Washington, of course. Political grandiosity is a feature of state capitals, too, and even of college campuses. Paul Phillipe Cret’s other important public works include the clocktower at the University of Texas at Austin, from which Charles Whitman inaugurated the modern age of mass shootings. But it wasn’t Whitman’s massacre that caused the university to close the observation deck to the public—it was accessible for years, until the university finally decided that too many suicidal students had leapt to their deaths off it. The tower is, given its bloody history, not an entirely inappropriate symbol of American life.

All in all, I’ll take a low-slung city of brick.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.