After weeks of collecting ballots from across the Last Frontier, Alaska is set to send Republican Lisa Murkowski and Democrat Mary Peltola back to Congress. This November marked the first general election using Alaska’s “top four” format, and it’s already making good on its promise to create a healthier political culture. Candidates on both sides recognized the need to look beyond their base for support, and the winners for federal office succeeded by mobilizing the broadest coalitions.

The new system is a substantial shift from how Alaska previously conducted elections. In place of partisan primaries and a “winner-take-all” general election, candidates from all parties now appear on one primary ballot, with the top four vote-getters advancing to an instant-runoff general election.

These reforms passed narrowly in 2020 via ballot initiative after receiving support from national organizations looking to reduce polarization and create a more functional government. Similar efforts are popping up across the country: A ballot measure passed in Nevada this year (and must pass again in 2024 to take effect), and a bipartisan group of lawmakers in Wisconsin introduced legislation to implement ranked choice voting last year.

Alaska first used its new system in a special election over the summer. Peltola shocked the political world by defeating two famous Republicans: Sarah Palin, the former governor and vice presidential candidate, and Nick Begich, the grandson of a former congressman and nephew of a former senator. Peltola provided the Democrats their first major statewide victory since 2008 and their first for the at-large congressional seat since 1972. She won the special election in part because tens of thousands of Begich supporters were turned off by Palin and abstained from ranking her as their second choice.

This phenomenon repeated itself once again in November, with even more Alaskans supporting Peltola this time. After she won a near majority in the first round, thousands of Begich voters gave the new congresswoman a full term.

That a Democrat won in Alaska is less surprising considering how Peltola campaigned. She ran as a moderate, emphasizing support for sustainable commercial fishing and earning endorsements from local oil and gas developers for her support for exploration projects on Alaska’s North Slope, despite strong opposition from the environmental lobby. After her victory, Peltola reintroduced a package of legislation brought forward by her Republican predecessor, the late Rep. Don Young.

Peltola’s bipartisan instincts extended beyond policy positions. At an October candidate forum, she reached out to the state’s many Republican voters and endorsed her longtime friend, Sen. Murkowski.

The incumbent senator also benefited from the new system, particularly the changes to the primary election. In partisan primaries, lower turnout and a limited electorate can provide undue influence to more partisan base voters—a phenomenon known as the “Primary Problem,” discussed on a past episode of The Dispatch Podcast. But in a blanket primary, where all candidates appear on one ballot, voters of all stripes have a say in who advances to the general election. The dynamic naturally benefits more moderate candidates like Murkowski.

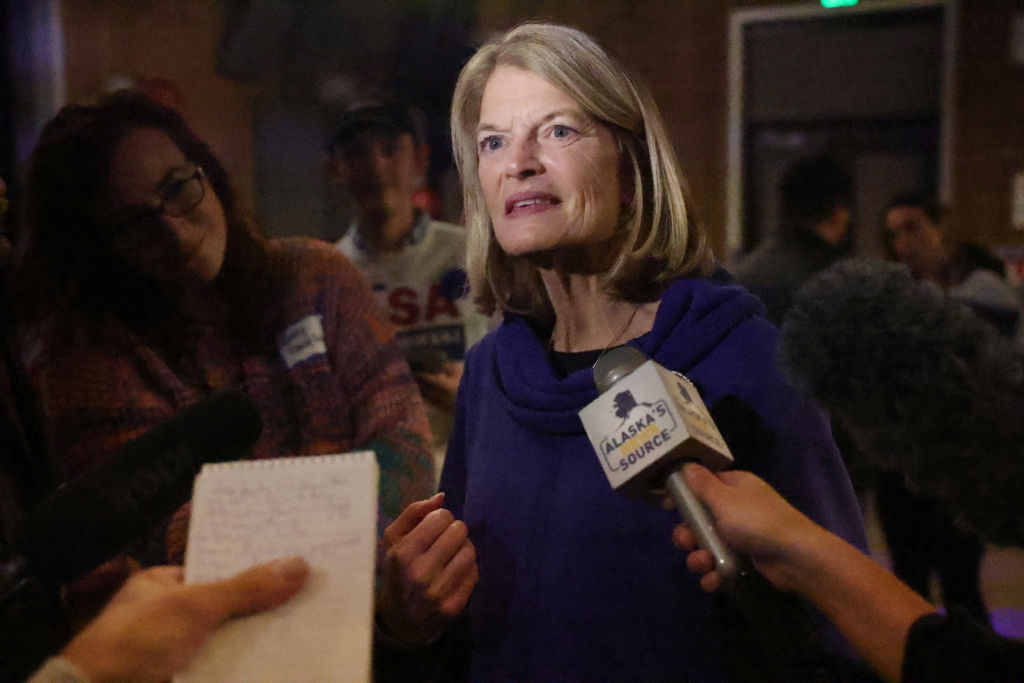

Murkowski, who is pro-choice and voted to convict Donald Trump following the Capitol riot on January 6, 2021, likely would have struggled against Trump-endorsed Kelly Tshibaka under the old primary system. Instead, Murkowski earned the most primary votes and advanced to the general election, where Democratic voters helped her reach majority support.

But the influence of the “top four” system was not limited to the winners. Both Republican House candidates changed their strategies after the August special election. Palin had been aggressive and confrontational toward Begich while campaigning during the special election, and complained frequently about the new electoral structure. Begich, meanwhile, cut ads calling out Palin for being a “celebrity” who quit and left Alaska.

However, both candidates took a friendlier approach in the general election. For example, when asked at a Chamber of Commerce forum who voters should choose as a second choice, Begich and Palin encouraged support for each other, telling voters to “rank the red.”

Simply changing how votes are cast and counted couldn’t end all strife between the two in the general election. At another candidate forum in Ketchikan, Begich slammed Palin for canceling the “bridge to nowhere,” an infrastructure project long sought by locals. Meanwhile, Palin called on Begich to drop out of the election. In spite of underlying animosity between the Republican candidates, the new Alaska system created incentives to reach out to each other’s voters. And in the general election, they did.

In the special election, Peltola won in part because Begich voters chose not to rally behind Palin. Only 50 percent of Begich voters ranked Palin as their second choice, with 29 percent choosing Peltola and 21 percent choosing neither. In the November election, however, after months of “rank the red” messaging, 67 percent of Begich voters ranked Palin second—a strong sign that the more cooperative messaging had an effect on voters and that the new system is changing the political climate.

Nonetheless, some national Republicans blame the new election system for their party’s defeat in the congressional race, and some state lawmakers are looking to roll it back in the 2023 legislative session. While they may be upset at losing the seat in a closely divided Congress, undoing the changes after one election cycle would be counterproductive. Republicans would be wise to forward a candidate that can capitalize on the party’s substantial registration advantage in the state. The short-term pain Republicans are feeling right now creates potential for long-term gains for which all Alaskans should be grateful.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.