Despite out-of-control government spending, the flagging economy, and a rapidly deteriorating global security situation, conservatives cannot seem to unite around a common vision for America’s future. Besides opposition to President Joe Biden and the Democratic party, what really unites Republicans as different as Reps. Don Bacon and Matt Gaetz?

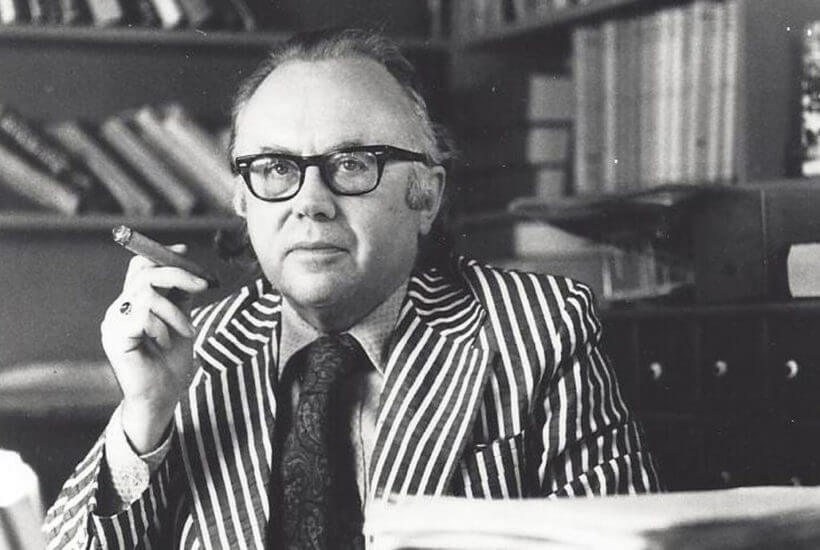

Amid this confusion and disarray, conservatives would do well to return to their roots. In 1953 Russell Kirk gave life to a vision of constitutional and cultural renewal in The Conservative Mind that animated the early movement and could inspire us today. On its 70th anniversary, it’s well worth reconsidering Kirk’s beautiful defense of our tradition and what it can teach us still.

Kirk’s conservatism is altogether different from what various factions on the right offer today. He was an ardent opponent of libertarians, whom he denounced as “chirping sectaries.” He considered their individualism a danger to traditional society. But Kirk was also a committed patriot and defender of the American constitution—it is doubtful that he would have much sympathy for the so-called “postliberals,” such as Notre Dame political scientist Patrick Deneen, who hold the founding in contempt.

Instead, Kirk was an advocate of ordered liberty. He believed that the American tradition is worth preserving because it found a balance between the need for meaning—“order”—and the importance of human freedom—“liberty.” Without some shared concept of an ultimate Good, Kirk believed society would descend into chaos and injustice. But without a due regard for the limits of power, society would sink into the horrors of tyranny. Western civilization as manifested in the heritage of cities such as Jerusalem, Athens, Rome, and London culminated for Kirk in the miracle of Philadelphia, the U.S. Constitution. In The Conservative Mind, Kirk called it “the most sagacious conservative document in political history.”

But what exactly is “conservatism” for Kirk? In the introduction to The Conservative Mind, he describes the book as a “prolonged essay in definition.” Rather than a rigid ideology, Kirk’s conservatism is a disposition of gratitude for our civilizational inheritance. He identifies several “canons” of conservatism, such as a belief in transcendent moral order, affection for the variety of life, and a reluctance toward hasty or thoughtless change. These attitudes are the substance of the titular “mind.”

The book is essentially a series of intellectual and political biographies of leading conservative thinkers from the French Revolution through the end of the 20th century. In each, Kirk demonstrates that conservatism is a “politics of prudence,” applying enduring principles to specific circumstances on behalf of the common good. Readers meet eccentrics such as Fisher Ames and John Randolph of Roanoke, novelists such as Walter Scott and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and political leaders such as George Canning and Benjamin Disraeli. These men all contributed much to Kirk’s conservative sensibility, but four tower above them as the great pillars of this body of thought: Edmund Burke, John Adams, Alexis de Tocqueville, and T.S. Eliot.

For Kirk, the Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke is the fountainhead of modern conservatism. His reaction to the French Revolution gives conservatives a playbook for opposing the “antagonist world” it unleashed. In Kirk’s words, Burke believed that “society is a spiritual reality possessing an eternal life but a delicate constitution,” one which “cannot be scrapped and recast as if it were a machine.” Nor did Burke believe society was a mere contract between its living members; rather, it is a bond between the dead, the living, and the unborn. Just as Publius supports reverence for the written Constitution in The Federalist, Burke advocates reverence for the unwritten constitution of custom and prescription. Burkean conservatism is not contemptuous of natural rights, but it prefers to focus on the natural duties we owe one another.

If Burke is the first conservative, then Kirk positions second president John Adams as the ideal American conservative. Unlike his more ideological opponent Thomas Jefferson or his more ambitious rival Alexander Hamilton, Kirk argues that Adams understood the true nature of the American constitution. Indeed, his statesmanship saved “America from the worst consequences of two radical illusions: the perfectibility of man and the merit of the unitary state.” Adams saw America’s complex system of checks and balances and divided sovereignty as a safeguard against both the revolutionary fervor of French Jacobins and the despotic designs of the Ancien Regime. He knew that America must be a republic of laws, because liberty without law is mere anarchy.

The only non-English speaking thinker profiled in The Conservative Mind is Alexis de Tocqueville. A student of both Burke and the American founders, Tocqueville saw in this republic an image of the new democratic age. “To inevitable democracy,” Kirk writes, Tocqueville “rendered the service of strict criticism and projected reform.” His warnings about soft despotism and the rise of an administrative state should gird conservatives for the fight to defend the Constitution. His analysis of federalism and the role of religion in American life point to ways to preserve our civilizational inheritance even during the upheaval of perpetual revolution.

Finally, Kirk turns to T.S. Eliot as a representative of “conservative’s promise” for future generations. His modernist poetry may seem like a strange object of admiration for an old Romantic like Kirk, but central to Eliot’s work is a conviction that “personal hope and public integrity” can be restored. Eliot and the other poets of The Conservative Mind teach the reader that conservatism goes beyond politics; it is also a vibrant literary and cultural tradition. Eliot reminds us that “the communication / Of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living.” By discovering how to tell old truths in new ways, Eliot models what conservative engagement with a changing culture can achieve.

While Kirk’s narrative is powerful, it is not without its shortcomings. Take, for example, Kirk’s somewhat misguided commendation of pro-slavery Democrat John C. Calhoun and his apparent exclusion of Abraham Lincoln. It is easy to understand why Kirk, a localist critic of the New Deal, would turn to Calhoun’s critique of centralization. But it is lamentable that The Conservative Mind does not fully reckon with the injustice of chattel slavery or with Lincoln’s more conservative defense of the U.S. Constitution and our Union. Although his admiration may not be perfectly clear in the book, Kirk lavishes praise on Lincoln as a conservative reformer elsewhere in his writing.

One of the most surprising elements of the book is its somewhat populist tone. Critics of Kirk’s traditionalism often pillory it for being overly aristocratic or contemptuous of democracy. Yet Kirk’s conservatism is “not ashamed to acknowledge the allegiance of humble men whose sureties are prejudice and prescription.” For Kirk, the ordinary folk understand the American tradition on an almost instinctual level, and he therefore has a fundamental confidence in the ability of the people to govern themselves. It is a confidence in the conservatism of the heart which endeared Kirk to the early movement—and which distinguishes him from so many right-wingers today.

When Henry Regnery published The Conservative Mind in 1953, it electrified the reading public. Progressive elites were scandalized by Kirk’s broadsides against liberal modernity, but many more readers were charmed by them. The Conservative Mind became a bestseller. Ex-communist Whittaker Chambers pushed for a vital review in Time magazine and referred to the book as “one of the most important to appear in some time.” William F. Buckley Jr. sought Kirk out as an early contributor to National Review. Ronald Reagan would hail Kirk as “the prophet of American conservatism.”

Kirk wrote that “Only just leadership can redeem society from the mastery of ignoble elite.” He believed that conservatives needed to provide an education for leadership that would produce not only great statesmen, but men and women who could lead in their own vocations nearer to home. Kirk was greatly concerned with the degeneration of the family, and believed restoring that fundamental institution was of the greatest importance. The Conservative Mind and his other writings are attempts to provide the “moral imagination” for a political, cultural, and vocational restoration.

Thankfully, Kirk’s students and family have kept his vision alive since his death in 1994. His widow Annette founded the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, which carries on his work by supporting traditionalist scholarship and leading seminars and events at Kirk’s ancestral home in Michigan and around the country. On December 5, for instance, the Kirk Center will host a panel in Washington, D.C., to celebrate The Conservative Mind’s 70th anniversary.

The time is ripe for what Burke once called “new exertions in the old cause.” Corrupt grifters and pseudointellectual ideologues cannot offer the substance the nation so desperately needs. Their cynicism and short-sightedness alienate the vast body politic of the American people. Russell Kirk’s exalted vision for American conservatism, on the other hand, is just what could reunite a divided party. Only a return to the American tradition of ordered liberty will “redeem the times.” Seventy years after its publication, a rising generation can still look to The Conservative Mind for real inspiration.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.