Ebrahim Raisi, known to many as the “Butcher of Tehran,” is being remembered for his brutality at home and belligerence abroad in his nearly three years as president.

Raisi, 63, died on Sunday along with the country’s foreign minister when their delegation’s chopper went down in northwest Iran, state media confirmed after a 15-hour search and rescue operation concluded with the early morning discovery of the destroyed aircraft. The circumstances around the crash are still unknown.

Within Iran, Raisi won the favor of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and the ire of the Iranian people for a track record of crushing political dissent dating back to the earliest days of his career. Throughout the Middle East, he helped strengthen Iran’s network of loyal proxies, setting the stage for Hamas’ October 7 attack and, months later, a direct confrontation with Israel. Internationally, he oversaw a period of immense tension between Iran and the West.

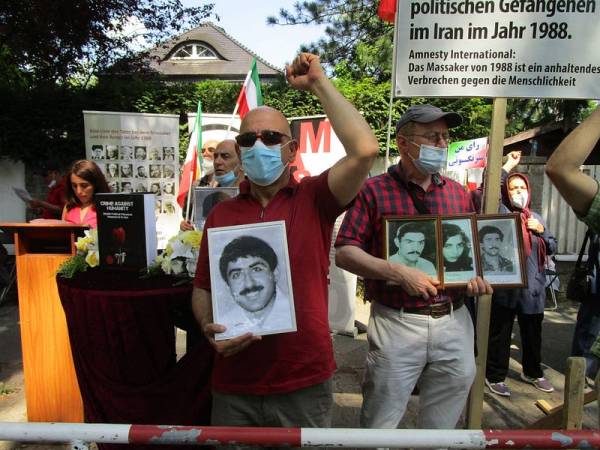

Raisi ascended the presidency in 2021, winning 62 percent of the vote in a contest pre-decided for Iranians through mass disqualifications and pressured withdrawals ahead of Election Day. Prior to taking office, Raisi rose through the ranks of Iran’s judicial system to eventually serve as chief justice of Iran between 2019 and 2021—a position in which he expanded the country’s use of the death penalty to punish political dissidents and to target ethnic and religious minorities. The number of yearly executions have risen steadily since. Last year alone, according to Amnesty International figures, Iran executed 853 people—the highest number recorded since 2015.

“His career was spent in one of the most repressive institutions in the Islamic Republic: its judiciary,” Jason Brodsky, the policy director of United Against Nuclear Iran, told The Dispatch. “His career is drenched in the blood of the Iranian people, and that’s why you saw many celebrating his demise with fireworks overnight. There is no love lost there.”

Raisi’s penchant for capital punishment dates back to the 1980s, when he oversaw the state’s arbitrary detention, torture, and mass killing of thousands of political prisoners. Among them was Farideh Goudarzi, who was arrested while in her third trimester of pregnancy and severely beaten by guards while Raisi—then-prosecutor of the Hamedan province—watched. “Raisi is the true representation of the entire Islamic Republic,” Goudarzi said in an interview ahead of Raisi’s election as president in 2021, urging Americans to “stop looking for so-called moderates within this regime.”

Indeed, it was Raisi’s cutthroat reputation that endeared him to Islamic Republic leaders increasingly beset with domestic upheaval. The regime—which faced mass anti-government protests in 2018, 2019, and 2020—likely hoped the new president’s notoriety would have a chilling effect on future dissent.

Not so. In 2022, morality police arrested 22-year-old Mahsa Amini for alleged hijab violations. Her eventual death at the hands of Iranian authorities set into motion the most significant wave of demonstrations in the country’s recent history, described by many as another revolution. Under Raisi’s leadership, the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement was met with a swift, severe government crackdown. Over the course of 2022 and 2023, security officials killed some 550 people and arrested more than 22,000 others.

In the Middle East, Raisi served as an implementer of the supreme leader’s vision of regional dominance. As president he often met with top officials from Iran’s various proxy groups, including Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh as recently as late March. A day after the terror group’s October 7 attack on Israel, Raisi hailed the “courage, bravery, resistance, and initiative” of its fighters, though denied that Iran had advance knowledge of the invasion. “Their resistance in this glorious operation is exemplary.”

Hamas, accordingly, mourned Raisi’s death in a statement Monday. The late president “supported the legitimate struggle of our people against the Zionist entity” and “provided valued support to the Palestinian resistance,” the Iranian-backed militants declared. They weren’t the only global pariahs to praise Raisi’s legacy. Russian President Vladimir Putin remembered the Iranian president as a “true friend” and an “outstanding politician whose entire life was dedicated to serving his homeland.”

Under Raisi’s leadership, Iran forged stronger ties than ever with Moscow, supporting Putin politically and materially in his 2022 invasion of Ukraine. When the Kremlin burned through munitions in the first months of the drawn-out war, Iran came to its aid by selling—and eventually helping co-produce—lethal attack drones to Russia. The explosive unmanned systems have been used on the battlefield in Ukraine to devastating effect. Putin called Iran’s interim president, Mohammad Mokhber, on Monday to assure him of Russia’s steadfast support.

Raisi personally supported pushing his country further into the Russia-China axis, forgoing grudging cooperation with the West and another nuclear deal with the U.S. to chart an aggressive Iranian foreign policy. In a fiery speech before the United Nations in September, Raisi held up his Quran and declared the end of a U.S.-led world order. “The global landscape is undergoing a paradigm shift toward an emerging international order,” he said, “a trajectory that is not reversible.”

With Raisi gone, the Iranian regime’s confrontational approach to the U.S. and Israel—ultimately set by the supreme leader himself—is unlikely to change. But it could set off a leadership crisis as 85-year-old Khamenei contemplates his successor. Many analysts viewed Raisi as the top choice, and his sudden death opens the door for other contenders, like Khamenei’s son Mojtaba—a shadowy figure with little popular support.

“Ebrahim Raisi was a leading contender to succeed Ayatollah Khamenei as supreme leader. He was the most experienced member of the Iranian establishment, having presided over two branches of government: the judiciary and the presidency,” Brodsky said. “It scrambles the politics of succession in the Islamic Republic.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.