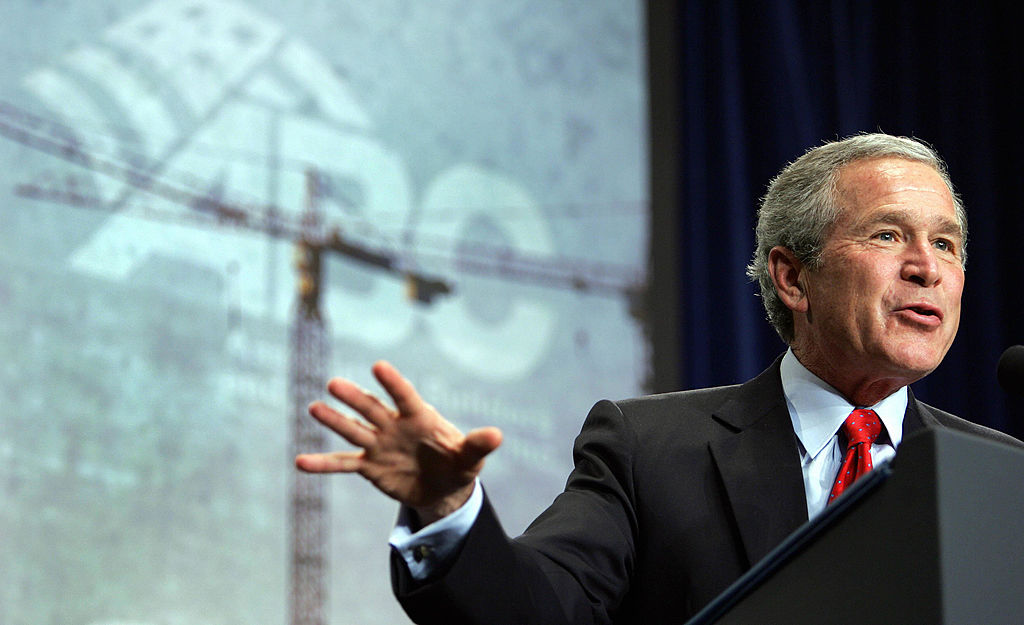

The history books probably will say three things about President George W. Bush:

- He was the last president of the Republican Party. The political vehicle that carries the burden of Donald Trump may still call itself the Republican Party and have the same mailing address and bank accounts, but it bears little resemblance to the political entity that preceded it. Whatever the failures of his administration, George W. Bush’s aspirations and principles were those of the organization that once boasted of being the “Party of Lincoln,” which no longer exists in any meaningful way.

- Bush’s presidency was a tragedy in an almost literary sense. The father had been the consummate 20th century man of international affairs, while the son, a very successful governor of Texas, aspired to make his own separate mark as a truly post-Cold War figure, one who would turn the nation’s attention to domestic affairs such as reforming education and entitlement programs.The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, forced George W. Bush to turn his attention to the Islamic world, and his presidency ultimately would founder in Iraq, meeting failure in the very place where his father had with such élan demonstrated the competency that comes from a lifetime of preparation for the task at hand.

- Though the cruelty of al-Qaeda and the cowardice of congressional Republicans gave him scant opportunity to act on his domestic priorities, George W. Bush’s model for reform—marketed under the brand name of “Ownership Society”—was the right one. This third item may seem like the least interesting of the three, but it could be the most consequential, and may yet prove to be.

The Wall Street Journal reports: “More Americans than ever own stocks.” In fact, a majority of U.S. households—58 percent—are corporate shareholders, either directly or indirectly through retirement accounts or managed funds. That is up from 53 percent in 2019—many Americans became investors, or more active investors, during the COVID-19 shutdowns and disruptions: Not all of those stimulus checks were spent on rare whisky and expensive sneakers.

One way of understanding the “ownership society” is this: The best way to spread the wealth is to spread the wealth.

If you are concerned that returns to labor are not keeping pace with returns to investment, then you could try to goose the labor market in various ways and pray to the gods of central planning that the unintended consequences of your monkeying around do not cost more than the value of whatever benefits you are able to achieve. Alternatively, you could encourage people who work for wages and salaries to invest in equity—and here I do not mean equity as the social-justice knuckleheads use the word but real equity—so that returns to capital end up in their pockets. Progressives talk about “putting people over profits,” but the “ownership society” understands that the relationship is not, or need not be, fundamentally rivalrous.

Napoleon supposedly spat that England is “a nation of shopkeepers,” being so ensorcelled by the prospect of la gloire that he could not appreciate what a fine thing it was to be a nation of shopkeepers—thrifty, prudent, commercial, not given to urgent enthusiasms. To be a nation of shareholders would be a very fine thing as well, for similar reasons.

We have, of course, been doing this with some success for many years, not only in the United States but around the world, with a great share of the world’s business enterprises being owned not by men with pinstriped suits and manicures but by ordinary people of ordinary means, in large part through retirement accounts and similar funds. The top 20 worldwide owners of assets—which hold something on the order of $27 trillion in investments—include the Government Pensions Investment Fund of Japan (which has long been at the top of the list), the Government Pension Fund of Norway, and the National Pension of South Korea, along with such U.S. representatives as the Federal Retirement Thrift and the public employees of California. The typical corporate shareholder in the United States does not look like Gordon Gekko—more like a retired teacher from Sacramento departing Port Canaveral on a weeklong cruise.

Americans like to talk about ourselves as though we were great pragmatists, interested only in “what works.” This is particularly true of a certain kind of American progressive who wishes to pretend that he does not operate from a set of ideological priors. In truth, Americans are a nigglingly moralistic people, able and eager to throw away “what works” if it rubs the wrong way against our sense of fairness, which is exquisitely tuned to detect slights down to the quantum level. One of the main obstacles to policies that encourage the accumulation of wealth in the United States are policies designed to discourage the accumulation of wealth in the United States, particularly intergenerational wealth. We seem to believe that a perfect society—or even a basically just society—requires an initial condition resembling the Platonic ideal of Lyndon Johnson’s hypothetical footrace, in which everybody starts from the same line in the same condition.

We Americans intensely dislike the idea that some people are going to do better in life because their families have money, hence the constant pressure (though it is not very effective) for higher taxes on inheritances and the similar pressure (somewhat more effective) to raise tax rates on investment income, which we call—because we cannot really tell the truth about anything—unearned. And so Americans are made to tithe into a public pension system that supplements incomes while discouraging (through the taking of income that could otherwise be invested) the accumulation of wealth that could be passed on to children and grandchildren because Franklin Roosevelt, a wealthy man, thought that felt like justice and convinced others of it. A system that encouraged more intergenerational wealth building would not be more fair, necessarily—but it would be wealthier, and that matters a great deal.

Of course, there are plenty of Americans who get ahead in life because of who their parents were. Some because their parents were wealthy, though there is less to that than you might think: Among very wealthy Americans, inherited money accounts for about 15 percent of their overall assets. Of course, that doesn’t capture all the ways in which well-off parents provide advantages to their children: That down payment on a first house may not end up being a very large piece of a new homeowner’s income at retirement or at the end of his life, but a well-timed boost can make an enormous difference, as can things such as not having to worry very much about paying college tuition or being able to take a low-paying but credential-building and relationship-making internship or first job without undue economic hardship thanks to parental support.

Other Americans benefit from having parents who might not have been very wealthy but who were very smart, tall, good-looking, fond of books, etc., or in possession of other highly beneficial and partly heritable traits. Many Americans get a leg up in life simply because of where in this unevenly blessed country they were born: The fact that I grew up in a college town rather than in a farming community 60 miles to the southwest certainly made an enormous difference in my life.

None of that is fair—but the results can be pretty good.

The constellation of policy ideas known as the “Ownership Society” are of of liberal and Thatcherite origin and were intended to give people ownership over the resources they require in life—and, hence, control over those resources and the dignity that goes with such control but which is undermined by having to beg bureaucracies for benefits. In the matter of pensions, that would look like allowing (encouraging, possibly requiring) Americans to invest some of the money they would have given up in payroll taxes (which, wink-wink, “fund” Social Security) in stocks and bonds and other financial assets or, more probably, in one of a few conservatively managed funds. In health care, ownership means having one’s own insurance and possibly a savings account dedicated to making copays and meeting other out-of-pocket medical expenses.

The pension part of that was a hard sell because investments involve risk, and the kind of people who end up depending on Social Security tend to be financially risk-averse; the health care side has failed to launch because its success requires that we first reform both health insurance and health care itself in order to achieve price transparency, predictability of coverage, etc. Your correspondent does pretty well on standardized tests and makes a pretty good living but really never can say with any confidence what his health insurance actually will cover in any given situation and what the out-of-pocket bill is going to look like, and his Ivy League-educated wife has more or less given up trying. For a great many people, an unexpected medical expense of a few hundred or a few thousand dollars presents a household economic crisis, and they do not want ownership of that crisis.

So for the ownership model to really work at a large scale, some prior reforms will be needed. We want an ownership model that makes people feel more secure and more in control of their own affairs rather than less.

It was always going to be complicated.

All that being stipulated, shifting to some degree (it need not be an either/or matter) away from government-administered benefits that make Americans clients of programs conditioned on the politics of the moment and toward helping Americans to build their own capacities by building their own wealth is the right thing to do.

It was the right thing to do 20 years ago, too, though apparently not the time.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.