Want an easy way to gauge how partisan a particular conservative is? Ask them whether they endorse the theory that the left being mean to Mitt Romney in 2012 led to the rise of Donald Trump.

Chances are, the more enthusiastically they agree, the more dependably they’ll keep voting Republican no matter how rancid the GOP gets.

The occasion of Romney’s retirement last week revived the “Mean to Mitt” theory on The App Formerly Known as Twitter, but it’s circulated in fits and starts for years. It goes like this: The Democrats and their media allies were so grievously unfair to Romney during the 2012 presidential campaign, and Romney himself was so pitifully weak about challenging them on it, that the right-wing base concluded it had no choice in the next presidential cycle but to hand over the party to a madman.

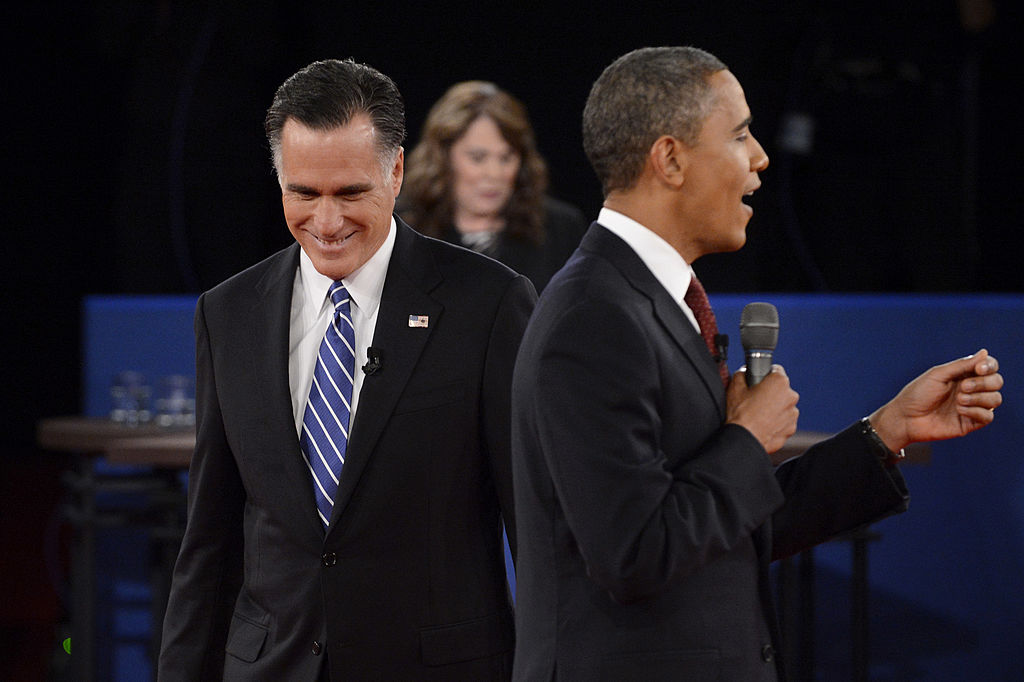

Anyone who’s worked in or around right-wing media over the last decade can quote chapter and verse of the “Mean to Mitt” theory. There was the left’s idiotic freakout over Romney’s “binders full of women” comment. Harry Reid’s repulsive—and false—smear about Romney’s taxes. Candy Crowley’s lie about Benghazi during a debate with Barack Obama. There were endless vicious shots at Romney’s character, of all things—his alleged personal cruelty, his racism, his, ahem, “gaffes.”

Mitt was bright, decent, and not terribly ideological, the sort of Republican to whom one might think the opposition would show a modicum of respect. Instead, for the sake of holding onto power, Democrats tore his throat out.

And Romney, being a milquetoast establishmentarian gentleman, took his lumps with a smile and said nothing. Just like John McCain did four years before him.

So what choice did Republican voters have in 2016 but to try something radically different by nominating a pugnacious authoritarian cretin?

I’m sure I’ve entertained the “Mean to Mitt” theory in the past, but I’ve come to doubt and even despise it over time. To endorse it in 2016, when right-wingers were grasping for ways to process what had just happened in their presidential primary, was one thing. To endorse it in 2023 reeks of excuse-making for the right’s descent into illiberalism. At some point in the past seven years, “Mean to Mitt” went from a descriptive narrative of how Republican voters had behaved to a normative rationalization for how Republican voters should behave.

The left was mean to Mitt, ergo we must embrace or excuse every degenerate impulse right-wing populists have.

That’s one reason to hate this theory. There are others.

The “Mean to Mitt” theory persists in part because it’s useful to both factions of the right.

Populists like it because it seems to provide an object lesson about the weakness of pre-Trump Republican elites. If you think the big problem with the Romney-era GOP was that it wasn’t ruthless enough, either in its policies or in demonstrating antipathy toward the left, 2012 is your QED. If only Mitt had been angrier in public at Harry Reid or Candy Crowley, who knows whether that 126-electoral-vote gap between him and Obama might not have evaporated.

Traditional conservatives like the theory even more than populists do.

Populists, after all, don’t want to give Trump’s political enemies full credit for his primary victory in 2016. They want it to be seen as a victory for his, and their, preferred policies too—protectionism, isolationism, post-liberalism writ large. Devout Trumpists would add that no one but the great man himself could have pulled it off, no matter what sort of post-2012 backlash was brewing on the right. In its strongest form, the “Mean to Mitt” theory reduces the glory of Trumpmania in 2016 to not much more than a temper tantrum by the Republican base.

That’s why conservatives, particularly anti-anti-Trump conservatives, like it. Partisans who are unhappy with the direction of the party find the theory appealing because it shifts blame for Trump’s rise from the right to the left and supplies an excuse to keep voting for the GOP. You see, it’s not that the Republican base disdains traditionally conservative policies and/or prefers authoritarianism to classical liberalism. Insofar as its voters behaved badly in 2016, they were simply driven to it by what the malicious Democrats and their media supplicants did four years earlier.

It’s the same Reaganite party that it’s always been! (More or less.) It just needs a bit more pugnacity in its leadership class. So it’s fine to go on supporting it while waiting for its temper tantrum to end.

The “Mean to Mitt” theory follows the same logic as the slogan, “This is how you got Trump.” That phrase was common among anti-anti-Trumpers during Trump’s presidency whenever the left overreached in pursuing its cultural agenda, whether by trying to defund the police or by, er, making salad emojis more vegan. It was another way for partisan conservatives to blame Trump’s ascendance on Democrats instead of on the people who actually voted for him, thereby excusing their own inexcusable decision to remain loyal to this increasingly illiberal statist party.

It implied, plainly, that supporting Donald Trump was understandable, if not downright advisable.

There’s a threatening undertone to both “This is how you got Trump” and to the “Mean to Mitt” theory that reminds me a bit of Trump’s “predictions” of violence this past spring if he were indicted. It amounts to saying that if the left happens to cross some wholly arbitrary line of political propriety, whether by mocking Mitt Romney’s “binders full of women” or vegan-izing emojis or what have you, the right can’t be held responsible for how it reacts. Everything is fair game, including nominating a conspiratorial anti-intellectual demagogue for president.

How liberating it must be for members of The Party of Personal Responsibility to know that they bear no responsibility for their political choices, and haven’t since November 6, 2012.

Another reason to hate the “Mean to Mitt” theory is that it’s very Very Online.

It’s not crazy to believe that Trump’s success owed something to Romney’s failure. Whenever I think of those two elections, in fact, I recall Sean Trende’s famous piece about “the missing white voters.” The missing white voters were downscale and rural, the same sort of culturally conservative but economically moderate cohort that was drawn to Ross Perot 20 years earlier. They didn’t show up for Mitt. But they did show up for Trump.

Trump ran on tariffs, repatriating jobs from overseas, and building a wall to keep illegal labor out. He complained frequently about aimless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The missing white voters liked that. Romney endorsed a “peace through strength” foreign policy, groused about “the 47 percent” who mooch off the federal government, and chose as his running mate a man bent on reforming the entitlements on which the working class relies.

The downscale white voters of America didn’t seem to like that as much.

Trump and Romney were also worlds apart in their ability to connect personally with people. Romney is polite to the point of being stiff, unfailingly awkward, and radiates country-club vibes. As a Massachusetts Mormon patrician who reminds blue-collar voters of “the guy who laid them off,” in Mike Huckabee’s memorable formulation, he was a strange match for a rural working-class Southern base. Trump, the foul-mouthed lout and pretend-Christian from Queens who speaks his mind and whose mien reeks of “new money,” was much better.

With so many differences between the two men working in Trump’s favor in 2016, the “Mean to Mitt” theory would nonetheless have us believe that some grievance borne by grassroots activists against Candy Crowley and the left for having been unfair four years earlier to Romney—a figure whom many of those activists don’t even like!—was some major factor in Trump’s primary victory.

I can’t believe I’m going to say this but … I think that’s unfair to populists. Even allowing for the fact that Republican primary voters are more activist-minded than most voters and therefore more willing to nurse grudges across election cycles, the “Trumpy populism was more in sync with the base on policy” theory of 2016 remains more compelling than the Very Online “Mitt should have yelled more at the debate moderator” alternative.

If you disagree, tell me why Ted Cruz—who was plenty eager to “fight” the media and other sworn enemies of the grassroots right—didn’t light the same spark in 2016.

Lurking within the “Mean to Mitt” theory is another dubious supposition, that Romney might well have won if not for the Democratic meanness directed at him and the lack of meanness he evinced in response. If the left had been less cutthroat and if Mitt had conducted himself more Trumpily, to coin a phrase, the outcome might have been different. That’s why it still stung so terribly, supposedly, in 2016.

I don’t buy that either.

There was nothing very remarkable in hindsight about Romney’s 2012 defeat. Incumbent presidents usually win reelection, and Obama was an excellent retail politician enjoying historic support from black voters. His approval rating was at break-even levels for most of the year preceding the election and began trending positive in September 2012. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate driven upward by the Great Recession had trended steadily downward since October 2009. In the home stretch of the race Romney was caught on tape complaining about “the 47 percent,” which may have ended whatever chance he had of convincing those missing white voters to turn out. By Election Day, according to Nate Silver, his odds of winning had shrunk to 8 percent or so.

It’s fair and fine to believe that vicious Democratic attacks amplified by the biased liberal press cost Mitt some of the 5 million votes that made up the margin between Obama and him. It’s preposterous, I think, to believe that they were decisive, and more preposterous still to conclude in the year of Our Lord 2023 that Donald Trump was a sound, logical answer to the base’s disappointment.

Never forget, after all, that despite the deck being stacked high against him, Mitt Romney claimed a larger share of the popular vote in 2012 than Trump did in either of his two races against opponents far weaker than Obama. That Democratic weakness combined with the just-so allocation of working-class white voters in battleground states more plausibly explains why Trump won one election and almost won another than, say, his penchant for “fighting” the media by posting moronic wrestling memes when CNN’s coverage got too hot for him.

Never forget either that when Democrats lost three straight elections in the 1980s, they didn’t declare that they had no choice but to turn to a left-wing authoritarian demagogue. They had an excuse to do so insofar as Republicans had been plenty “mean” to them: 1988 was the year of the infamous Willie Horton ad, when one of the most notoriously cutthroat operatives in U.S. history, Lee Atwater, ran George H.W. Bush’s presidential campaign. Michael Dukakis was crushed that fall, the third landslide defeat in a row for the left.

Democrats could have whined in 1992 that the right had been “Mean to Mike” and responded by nominating the fringiest populist they could find. Instead they nominated Bill Clinton, an establishment neoliberal, and have nominated similar figures in every election since. With one exception, they’ve won the popular vote every time.

The right responded to its own electoral disappointment differently, and has gotten different results. Seven years later, devotees of the “Mean to Mitt” theory are still inexplicably making excuses for them.

But that’s not what really bothers me about this nonsense.

What really bothers me is that one would think if anyone were entitled to choose radicalism because the left was mean to Mitt Romney, it’s Mitt Romney.

He hasn’t. Rather the opposite.

Populists refuse to follow his example. In fact, many who are most eager to use the “Mean to Mitt” theory to justify their radicalism seem to detest Mitt Romney personally. Some may detest him because he champions the Reagan-era policies they’ve come to despise, some because he’s become a symbol of classical liberalism. But most detest him, I suspect, because he twice voted to convict the terrible man to whom they’ve sworn allegiance.

Whenever you hear someone prattling on about how vicious Democrats were to him in 2012, I’d ask you to consider how much much physically safer Romney would be in 2023 at a Joe Biden campaign event than at a Donald Trump one. There’s a reason he’s paying $5,000 a day in personal security for himself and his family since Trump’s first impeachment trial, and it’s not because he fears a mob of crazed left-wingers ranting about “binders full of women” might descend on him.

If you’re still grousing about how badly the left treated him more than 10 years ago instead of how badly the right is treating him today, why are you doing that? Which problem do you suppose Mitt Romney himself would say is more urgent, and more revelatory about the nature of the two major parties?

It’s enough to make a cynic suspect that most Trump supporters don’t care much at all about how Romney was treated in 2012 except insofar as they can exploit any lingering sense of grievance over it as a license to behave with utmost ruthlessness. To wave Romney’s bloody shirt at the left figuratively while quietly (or not so quietly) wishing that you could bloody his shirt literally is to master a degree of political cynicism that would make even Atwater blush. There’s no dignity in fascism, but pretending that you were forced into it by your enemies instead of admitting that you chose it freely is especially undignified.

If we simply must excuse Republican voters for their indefensible Trump support by placing the blame elsewhere, let’s at least eschew the “Mean to Mitt” theory and place it on a more plausible culprit: right-wing media. Many GOP primary voters spend their online lives neck-deep in a sewer of conspiracy theories, demagoguery, dopey tough-guy bravado, and apocalyptic antipathy to an “establishment” they would struggle to define if forced to do so. So deep does the nihilism run that, as I write this, the Republican majority of the House is poised to force a government shutdown because a critical mass of representatives on the right … wants a government shutdown. Seemingly just to prove that they’re willing to do it.

That’s been the tone of right-wing media for years. There’s a reason, after all, why Mitt Romney felt obliged to accept Donald Trump’s endorsement in person in 2012. Trump had earned some cachet among Republican voters the year before by mirroring their paranoia about Barack Obama’s missing birth certificate, a popular topic in online conservative media during that era, such that Romney didn’t feel comfortable alienating him. Right-wing media has gotten vastly worse since then—yet conservative “Mean to Mitt” devotees typically have little to say about it. Mainstream media remains the eternal scapegoat for partisan media’s failures.

I ask you: Logically, which seems like it would be more influential in shaping the average right-wing voter’s demagogic preferences? Candy Crowley doing Mitt Romney dirty at a debate with a poor fact check or a 10-year daily media diet of paranoia from Breitbart, Gateway Pundit, the Daily Wire, Steve Bannon’s podcast, etc?

In the end, though, I don’t think it’s fair to blame right-wing media either, as malicious as they are. The blame lies with the voters, always and ever. They asked for this.

There are no excuses for Trump. Stand in front of a mirror and say it, repeatedly if necessary: There are no excuses for Trump. I’d bet good money that Mitt Romney agrees.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.