Dear Capitolisters,

Most discussion of President Joe Biden’s State of the Union Address has probed the issues on which Republicans and Democrats disagreed—often vocally (sigh). Today, however, we’re going to look at one issue that elicited not only bipartisan agreement but an actual standing ovation: “Buy American.” A few Capitolisms have touched on this policy, which generally restricts federal funds to goods and services made domestically, but we’ve never really gotten into its many, many weeds. And since those weeds are unfortunately growing—and getting mad applause from our political class—it’s time we examined them.

What Is ‘Buy American’?

We talk about “Buy American” as a single U.S. law, but, as my Cato colleague Colin Grabow recently documented, there are actually several different “localization” restrictions tied to federal government spending. The most notable ones are as follows:

- The Buy American Act of 1933 requires federal agencies to give a procurement preference to items that have been “manufactured in the United States substantially all from articles, materials, or supplies mined, produced or manufactured” domestically. Because the law didn’t define “substantially all,” presidents have monkeyed around with the definition. It used to be 50 percent, but then Trump increased it to 55 percent, and now Biden has pushed it to 60 percent, promising to increase it again to 65 percent in 2024 and 75 percent in 2029.

- The Berry Amendment of 1941 requires Defense Department purchases to be 100 percent domestic in origin if falling into one of five categories: textiles, clothing, footwear, food, and hand or measuring tools (including flatware and dinnerware). A subsequent restriction for “specialty metals” was added in 1973.

- The Kissell Amendment of 2009 (in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act) requires the Department of Homeland Security to purchase American-made textiles, clothing, and footwear.

- The Military Cargo Preference Act of 1904 and related maritime statutes (including, of course, the Jones Act) require the U.S. military to use U.S. vessels for transporting cargo and personnel and to use certain other goods (e.g., anchor chain) that are American-made.

- The Buy America Act of 1978 and related statutes apply to federally funded transportation projects—highways, public transportation, aviation, intercity passenger rail (including Amtrak), water infrastructure, etc.—even when carried out by states or localities. Content thresholds vary by product but, importantly, iron, steel, and related manufactured products are subject to a requirement that they be wholly (100 percent) made in the United States.

- Finally, the new Build America, Buy America Act (BABA) was buried in the thousand-page, trillion-dollar Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) of 2021, and it expands traditional U.S. localization requirements in two ways: 1) It covers most public works projects (dams, buildings, electrical transmission facilities, etc.), not just transportation and water‐related stuff; and 2) it covers the usual iron/steel products, plus nonferrous metals (e.g., copper), plastic‐ and polymer‐based products, glass, composite building materials, lumber, and drywall. This law was what President Biden was discussing in the SOTU.

Finally, there are dozens of lesser-known Buy American restrictions that apply to specific goods or services, ranging from the obvious (defense-related goods) to the absurd (furniture in the White House, school lunches, etc.). State-law equivalents to Buy America, sometimes requiring in-state (not just in-country) purchases, can often restrict procurement even further.

America’s notorious “free market fundamentalism” strikes again! Sigh.

Anyway, Buy American laws also have numerous exceptions. Most notably, agencies can avoid buying local if it’s too costly (i.e., if the U.S. version is 20, 30, or even 50 percent more expensive than a foreign alternative); if there’s simply no U.S. version available in sufficient quantities or of a satisfactory quality; if a preference for U.S. goods is “inconsistent with the public interest”; or if the product at issue comes from a country with which the U.S. has a reciprocal trade agreement—mainly defense-related ones (27 countries, mainly in Europe), free trade agreements (20 countries), and the World Trade Organization’s Government Procurement Agreement (48 parties, including 27 EU states).

However, contrary to widespread allegations from politicians and cronies that these exceptions are routinely abused, in reality they’re not used all that often: As Grabow notes, for example, the Government Accountability Office found that foreign-made end products accounted for a mere 4 percent of federal government purchases in fiscal year 2017 ($7.8 billion of $196 billion), and “almost all of these purchases were either for use outside of the United States or were from countries with which DOD has procurement agreements allowed under the public‐interest exemption.” A subsequent study from the Peterson Institute found that imports of all types of goods (not just end-use) and services were just 7.5 percent of U.S. procurement spending in 2014—the lowest share of the six economies examined.

Probably the biggest reason for this lack of use—beyond executive the bureaucratic arcana—is that U.S. procurement agreements have numerous exceptions for things like state and local procurement (where a ton of tax dollars are spent) and specific industries or projects.

In other words, our exceptions have exceptions. (Lawyers, man. Lawyers.)

Documenting the Many Harms of Buy American Laws

Contrary to the political rhetoric, forcing federal contractors to use U.S. goods and services generates all sorts of economic harms.

Increased costs. Most obviously, Buy America policies significantly increase the cost of federally funded projects and thus waste taxpayer dollars—something the laws themselves openly admit (recall: You can buy foreign only if it’s 20 to 50 percent cheaper). As the New York Times’ Peter Coy notes in a recent column, this cost is also just common sense: “If the American-made products were cheaper, better or both, there would be no need to force agencies to buy them. … So either the requirement is harmful to the customers in the federal government and, by extension, taxpayers, or it’s superfluous.”

Studies have long backed up these intuitions: Economists have repeatedly found that government procurement restrictions act as a barrier to entering the U.S. market and thus raise domestic materials prices—and thus total project costs—in the same way that a tariff would. The aforementioned Peterson paper, for example, found that Buy American rules were the equivalent of a 26 percent tariff on subject imports, thus raising the prices of domestic equivalents by almost 6 percent and costing the U.S. government roughly $100 billion (2022 dollars) per year in added costs as compared to a “Buy Almost Anywhere” alternative. An older paper found similar things (an “implicit tariff” of 26 to 43 percent). Peterson separately calculated that state-level barriers are another 10 percent tariff equivalent, further increasing costs.

Unfortunately, this damage isn’t limited to wonky studies; instead, the real world is littered with examples of Buy American’s unnecessary costs. Here’s transit expert Alon Levy summarizing the money we throw away on trains (emphasis mine):

New York’s next train model, the R211, will finally replace the R44s at a cost of $3.7 billion, or about $130,000 per linear meter. Bilevel cars for Caltrain and New Jersey Transit cost about 35 percent and 60 percent more than their European counterparts respectively, the New Jersey Transit order also burdened by compliance with obsolete regulations. A Los Angeles light rail vehicle order from the last decade went up to $3.8 million per car or $140,000 per meter of train length (the average cost in Europe is under $100,000 per meter), while a San Francisco one went up to $170,000 / meter. In Boston, an order with little premium, built at a new factory in Springfield, Massachusetts, was given to Chinese manufacturer CRRC. But European and Japanese vendors had bid $135,000/meter, leading to worries about Chinese dumping and a congressional investigation…..

Other than the New Jersey Transit commuter trains, the trains detailed above aren’t technologically different from their European or East Asian counterparts, just more conservative in their lack of open gangways. And yet, they cost 30-70 percent more.

Numerous other examples—overpriced (and defective) subway cars, insanely costly bridges, expensive transit buses, and so on—abound. At one point a few years ago, a Canadian company actually ripped perfectly good pipe out of the ground because it was labeled “Made in Canada.” And it’s all on American taxpayers’ dime.

Added complexity, paperwork, and delays. Perhaps the biggest Buy American cost, however, isn’t in dollars but instead in time and complexity, as U.S. companies and government agencies have long struggled to comply with arcane localization rules and document that compliance. According to the Congressional Research Service, in fact, a mid-1990s survey of public transportation industry officials cited Buy America “as the cause of project delay more often than any other reason.”

It’s only gotten worse since then, as Buy American restrictions have multiplied and presidents have gotten stingier about the exceptions. For example, the 2009-2010 implementation of all those “shovel ready” projects funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act suffered myriad complications and delays because contractors and state and local government officials couldn’t easily navigate the law’s beefed-up Buy American rules. This was particularly hard for small businesses, as one executive explained in 2009:

The result of the Buy American provisions has been a paperwork nightmare. Every project that is even partially funded by Recovery Act funds is required to fulfill the paperwork requirements. This means that every participating contractor, supplier, and manufacturer is must fill out and submit a different set of paperwork certifying that the parts being supplied meet the Buy American clause of the Recovery Act. Every part, even a $10 one, requires certification, paperwork and proof that it fulfills the “Made in the U.S.” requirements. Waivers are difficult to obtain and are rarely granted. In sum, the provision is causing huge delays, and the confusion regarding the provision is stalling otherwise viable projects. It is discouraging both companies from pursuing projects and contractors from bidding on projects.

But, hey, at least the lawyers were happy.

Buy American compliance doesn’t end when funds are disbursed, either, so federally funded projects can experience even more delays, if not worse (emphasis mine):

A [Federal Transit Authority (FTA)] request to review Buy America compliance for a $2.3 million reimbursement agreement for gas relocation in Sacramento delayed the relocation by one year. It was eventually completed at an increased cost of $4.3 million. Another instance there involved the replacement of a lot valve, in which a small number of valves were found to be non-compliant with Buy America. While it would have only cost $100,000 to produce a replacement in the United States, the agency learned that the manufacturing process and safety certification would take at least 62 weeks, likely resulting in a project cost increase more than 10 times the value of the actual part.

Central to these complications and delays are the domestic content requirements that Trump and now Biden keep increasing—rules that may have worked in bygone eras but make no sense in a 21st century world of increasingly complex products and constantly changing global supply chains. Today, documenting the contents and origins of every product—especially ones that, say, a construction company needs but doesn’t make—is painstakingly difficult and costly (if not outright impossible in some cases). One county official put this well back in 2009: “The [Buy American] rules affect a small part of the project but are like a virus infecting the whole thing. … It’s like they want us to go back in time.” I couldn’t have said it better myself.

And, as National Review’s Dominic Pino noted last week, determining what’s “local” is also open to interpretation: “components” need to be local but “subcomponents” don’t, so a “Made-in-America” standing desk can magically become “Not-Made-In-America” depending on whether a Chinese motor is deemed a “component.” Thus, litigating Buy American’s intricacies can become a battlefield for lawyers and competitor companies—leaving the rest of us worse off in terms of both cost and project delays.

There may be no better example of this problem than New York City’s insanely costly, long-delayed Second Avenue Station (SAS), which received federal funds and was thus subject to Buy America. Back in 2011, New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) approved two contractors’ use of Finnish fire suppression systems that, after months of MTA study, the agency had determined to be Buy America-compliant. In 2013, however, a competitor company got wind of this contract and complained to the Federal Transit Authority, which, after a lengthy formal investigation, overruled the MTA in 2015 (yes, four years later!) and demanded that the agency replace the systems with American-made ones. One system had even been purchased already. Sadly, that wasn’t the only Buy America-related problem for the project: giant, custom granite archways were another.

And then we all scratch our heads and ask, “Why It Took a Century and $4.5 Billion to Add Just Three Subway Stops in New York City.”

Gee, I wonder.

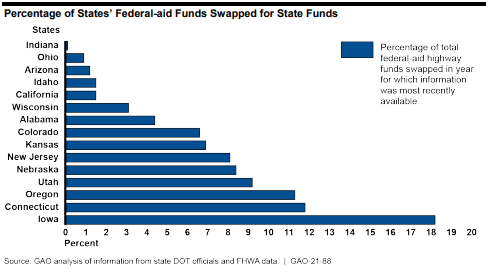

Revealed preferences. Perhaps the easiest tell that Buy American restrictions are a serious burden is that U.S. government entities—not ruthless multinational corporations or dastardly foreigners—keep trying to avoid them. For example, more than a dozen states have enacted “federal-aid swap” laws that allow local agencies to swap their federal highway funds for state transportation funds, usually for a small fee, in order to implement local projects with state funds and thus avoid federal restrictions like Buy America and “Davis-Bacon” wage requirements. According to the GAO, “state departments of transportation … and selected local agencies said that they participate in fund swapping because it increases project flexibility for local agencies and may result in time and cost savings.”

As economist Evan Soltas notes on Twitter, that localities are willing to pay—in time and money—to avoid federal Buy American and other restrictions shows that the compliance costs are even higher (a “revealed preference”). Indeed, even the Biden administration has implicitly acknowledged these compliance problems when it temporarily delayed BABA’s restrictions so that federal projects could get underway more quickly (and, coincidentally I’m sure, before the midterm election).

As this waiver period wound down late last year, several state agencies warned of dire consequences for various infrastructure projects: The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials expressed concern “that the quick implementation of Buy America requirements for such a broad range of materials will cause delays in project delivery while states, contractors, manufacturers, and suppliers continue working to determine how best to track and verify these materials.” The American Public Transportation Association, which represents transit agencies, warned that the restrictions could lead to a “doubling, tripling or even a quadrupling of costs for construction materials.” The North American branch of the Airports Council International said that a failure to extend the waiver “is short-sighted and unnecessarily risks reducing the number of airport construction projects and associated U.S. construction jobs.” Specific states, such North Carolina, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming, echoed these sentiments.

As the SOTU made clear, the Biden administration has denied these requests and is pressing forward with the BABA restrictions. I’m sure it’ll all go swimmingly.

But Wait, There’s More

What I’ve discussed so far are merely the seen, direct costs of U.S. Buy American policies. Less seen are all the other costs that this protectionism inflicts.

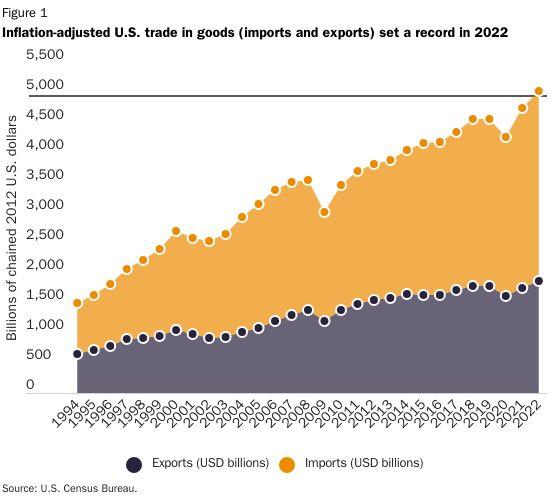

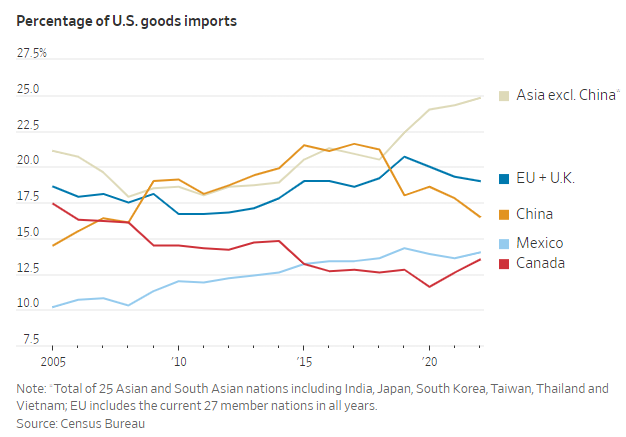

Fewer exports (and more diplomatic angst). Major U.S. companies like Caterpillar and General Electric have long opposed the expansion of Buy America rules out of a well-founded fear that foreign governments, which typically have larger procurement sectors than we do, will bar them from bidding on government projects (a $5 trillion market for developed economies alone.) That’s a particularly foolish move, given that U.S. companies have a comparative advantage in many of the industries at issue:

[A] large share of government procurement entails goods, services, and projects that are US specialties. Major construction firms like Bechtel, Fluor, and Kellogg excel at port, power, and bridge construction. Outside the United States, most hospitals are government-run, and US medical equipment firms like Philips Healthcare, Carestream Health, and Hologic are prime suppliers of CAT and MRI machines, dialysis equipment, and operating theaters. US pharmaceutical firms like Merck, Pfizer, and Gilead are leading producers of medicines, widely purchased by governments abroad. Like the private sector, the government relies heavily on information technology—requiring all manner of computers and software—a specialty of American firms like Dell, IBM, Cisco, Oracle, and Microsoft.

And, as we rediscovered last decade with Europe and Canada (and are re-re-discovering today with the IRA), this tit-for-tat “buy local” protectionism makes it harder for allied governments to cooperate on other economic or geopolitical issues (e.g. on China). Unfortunately, a new assessment of OMB’s just-released BABA rules—from former USTR procurement negotiator Jean Gier—indicates that the Biden administration could ignore our trade agreement obligations when implementing BABA, thus risking even more international conflict over U.S. trade policy and retaliation against U.S. companies in these markets.

Unintended consequences. As is so often the case with U.S. industrial policy, Buy American policies also produce numerous unseen distortions throughout the economy, often undermining the government’s own policy objectives. One of my favorite examples of this problem comes from a 2014 paper that found that restrictions tied to federal transportation subsidies pushed local transit agencies to buy American-made buses that were both more expensive (“buses in Tokyo and Seoul are half the price of U.S. buses”) and less fuel efficient. As a result, Americans got lower quality, less-available public transit, increased traffic congestion, and more environmental harm. The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson adds that the government rules also discouraged domestic bus producers from innovating: “One lesson of this paper is that Buy American provisions might send a strong signal to buyers—whatever you do, just buy from one of these few domestic suppliers!—that overwhelms other signals, such as price and quality. As a result, domestic suppliers don’t have to keep up with any innovative wave, and Buy American policies lock parts of the economy into being less innovative.”

These unintended consequences, of course, aren’t isolated to transit buses—they are the obvious and inevitable result of a government policy that intentionally prevents participants from implementing other government policy as efficiently and effectively as possible. As Grabow notes, for example, a 2019 government advisory panel report warned that Buy American and the Berry Amendment prevent the U.S. military from accessing cutting‐edge products and are thus “antithetical to efficiently procuring the most advanced readily available products and solutions.” Telecommunications and water companies have raised similar concerns about the new BABA restrictions, arguing that they’re out of step with today’s global supply chains and will preclude the use of the latest and most innovative technologies. Even “onshoring” success stories can turn into a “disaster” when companies do the regulatory minimum to win those sweet, sweet subsidies, or when American manufacturers (and their workers) are excluded from federal projects on a technicality.

Macroeconomic costs. Like all protectionism, Buy American also imposes broader costs on the U.S. economy by directing finite resources to less-productive endeavors. While mapping these harms is always speculative, a 2017 paper employed an economy-wide (general equilibrium) model to see what would happen if certain Buy American restrictions were scrapped and the procurement cost savings were returned to taxpayers. The results: 306,000 net new jobs, $22 billion in additional economic output (GDP), and a negligible impact on U.S. manufacturing (because the sector is “not strongly dependent on Buy America(n)”). Assuming the government didn’t return the savings (a safe assumption), you’d still surely see important economy-wide benefits from ditching these procurement rules: more construction jobs, faster and better government projects, more innovation, higher wages, etc. The study’s authors conclude that, “it is clear that Buy American fails as a policy to promote aggregate employment and economic growth.”

Shocking, I know.

Summing It All Up

So Buy American rules cost a lot, deliver little, undermine government objectives, and produce a litany of other distortions. They’re like a tariff, but—given the bureaucracy, uncertainty, opacity, and direct connection to other government policies—much worse. As such, Buy American routinely offends folks on both the left (because they confound government projects and have a sordid past) and the right (because they waste taxpayer dollars and expand bureaucracy). And such offense is only amplified by the fact that both sides are increasingly fed up with rising construction costs and our nation’s seeming inability to build stuff quickly, and that, as Coy notes, the U.S. economy’s not exactly desperate for more lumber and drywall jobs.

So why are these restrictions not only persisting, but actually being expanded in both Democratic and Republican governments?

Well, beyond the fact that “Buy American!” sounds great and easy, and that “job-ism” brainworms continue to infest our political class regardless of the historically low unemployment rate or historically high job openings, the answer is unfortunately the same one we confront all the time around here: politics. In particular, old Buy American rules have very specific and concentrated beneficiaries that lobby heavily to maintain them. These and other industries also lobby to expand the restrictions—the steel industry did a few years ago and, as Pino showed, most of the industries mentioned in Biden’s SOTU and preferred in the BABA (lumber, glass, fiber optics) have been deeply engaged in Washington for a while now. And these companies’ math is, unfortunately, undeniable: Per Grabow, for example, protectionist poster-child New Balance spent a measly $230,000 in lobbying to win a $17.3 million shoe contract in 2014 that only the protectionist Berry Amendment ensured. Sure, those lobbying dollars could’ve been spent on more productive purposes, but—when the law and elected officials are so eager to dole out easy taxpayer money, and when voters are mostly unaware of the aforementioned problems—it’s not exactly irrational for C-suite cronies to take the easy way out, irksome though it may be. Throw in a president who’s already laser-focused on winning his next election via a “yearslong push to persuade white working class voters,” and you get $100 billion in annual waste, fewer and slower government-funded projects, and a clunkier U.S. economy.

But that doesn’t mean we should be happy about it, and it sure as heck doesn’t warrant a standing ovation.

Chart of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.