Hang around the policy game long enough, and you’ll encounter the argument that government should use tariffs, subsidies, “Buy American” rules, and related policies to protect and expand the U.S. manufacturing sector because it’s special, both economically and in the eyes of the average American voter.

In recent weeks, for example, American Compass’ Oren Cass justified Trump-style tariffs because, in his words, “making things matters”—a slogan he repeated when unveiling new (and expressly anti-globalization) polling from his organization showing that Americans overwhelmingly “agree that ‘we need a stronger manufacturing sector.’” Usual tariff and push-poll concerns aside, this sloganeering is nothing new for Cass and certainly not limited to him or other protectionists on the American right. In fact, given the 2024 presidential election, its increasingly certain (alas) participants, and recent U.S. policy history, you can bet that proactively reviving American manufacturing will be a top issue. And protectionists will frequently base their demands on the simple and unstated assumption that the sector has long been a shambles, and that the production of tangible “things” deserves extra government attention.

Dig a little deeper, however, and the issue isn’t so simple.

We Already Make Lots of Things

Although not the main point of today’s newsletter, it’s still important to note up front here that the United States still makes lots of “things”—lots.

We discussed much of this a few years ago, but my Cato colleague Colin Grabow’s new essay on American “deindustrialization” updates the data and comes to the same conclusion. Here are a few examples:

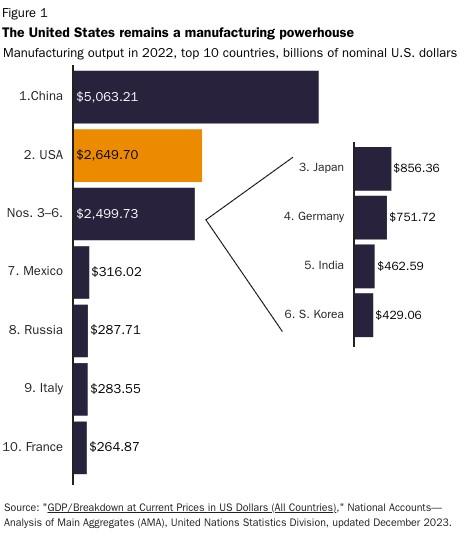

- In 2021, the United States ranked second in the world in terms of total manufacturing output—greater than the output of Japan, Germany, and South Korea combined. The 2021 U.S. manufacturing sector by itself would’ve constituted the world’s eighth‐largest economy that year. The United States was the world’s fourth‐largest steel producer in 2020, second‐largest automaker in 2021, and largest aerospace exporter in 2021.

- The latest data show continued U.S. strength in 2022, with production ($2.65 trillion) substantially exceeding the combined sum of those three industrial powerhouses and India too ($2.5 trillion):

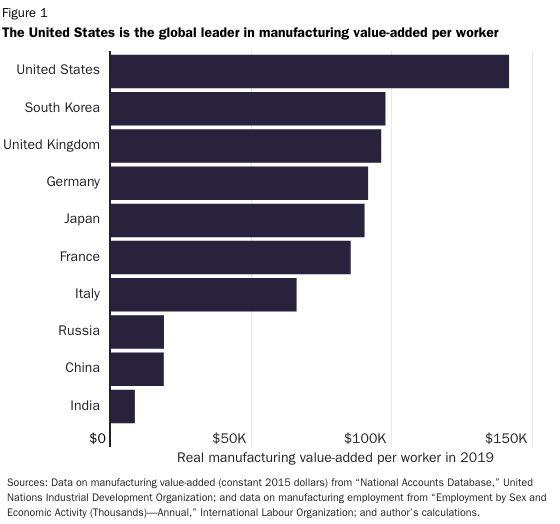

- China, of course, manufactures even more stuff than the United States, but its manufacturing sector does so with a lot more people and thus suffers, as we’ve previously discussed, from relatively low productivity. The United States, by contrast, is just the opposite: We achieve our high rankings with a relatively small industrial workforce—a testament to our world‐beating productivity and, as we’ll discuss in a second, dominance in non-manufacturing sectors too:

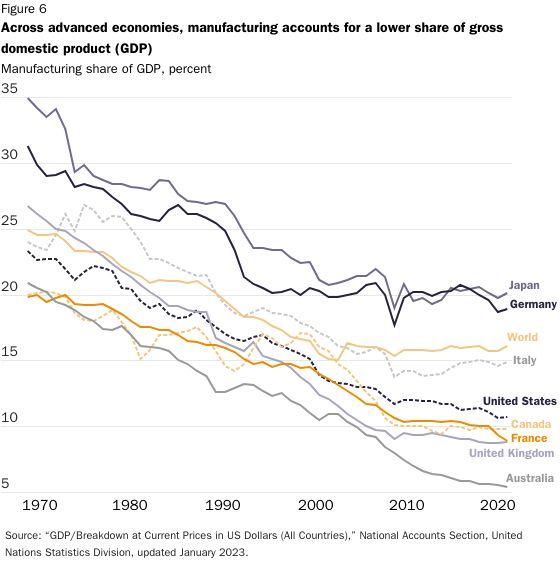

- On a historical basis, meanwhile, the U.S. manufacturing sector is also doing fine, with both gross output and value-added (basically, output minus costs) hovering around their all-time highs. Previous decades’ increases in these topline numbers did stall out in recent years, but beyond the aforementioned global rankings that trend is no reason for concern, regardless of how you measure it. As we discussed a few years ago (and see this paper for more), some of this manufacturing “stagnation” is because significant expansions in higher-value U.S. production like energy, chemicals, transportation, pharmaceuticals, and aerospace were offset by historical declines in dying or less-advanced (and lower-paying) U.S. industries like tobacco, paper, textiles and apparel, footwear, and furniture. Perhaps more importantly, there’s just no good economic reason to expect total U.S. manufacturing output to expand forever. By contrast, there are plenty of reasons why it shouldn’t: Among them are the continued “dematerialization” of production in wealthier economies (we make more stuff with fewer materials), the natural development of poorer countries away from agriculture and into manufacturing (or away from self-defeating communism), and the long-term trend in all nations to consume relatively more services (and fewer goods) as they get richer—a trend closely linked to manufacturing output.

Other U.S. manufacturing metrics—foreign investment, exports, capital expenditures, etc.—show similar things. In short, if you’re worried about the United States “making things,” then you can stop worrying.

The Changing Nature of ‘Making Things’

A simplistic focus on manufacturing output and jobs—on “making things”—also ignores the sector’s increasing complexity and ambiguity.

First, and as indicated above, there are many “things” that—thanks to good ol’ comparative advantage—a rich, open country like the United States probably shouldn’t be making in significant quantities. (And, as Grabow notes, that American workers aren’t super-eager to make.) As I showed in a 2021 paper, average hourly earnings and earnings/jobs growth in many U.S. manufacturing industries—textiles/apparel, wood products, food processing, etc.—were well below the averages for most U.S. services industries (basically everything but leisure/hospitality and retail) and U.S. private sector as a whole. (See Table 5.)

And this advantage isn’t limited to white collar work: As I highlighted in that paper and elsewhere, many blue‐collar services jobs in the United States not only have grown faster than manufacturing jobs since 1990, but also pay higher hourly wages, have faster wage growth, and are more plentiful. Far better to let people in other countries make these “things” and to pay for it with the money earned from specializing in the production of other, higher value (and safer and cleaner) goods and services. Protectionist policies like a 10 percent baseline tariff—which Trump has proposed and Cass has defended on “making things” grounds—ignore all of this.

Second, and speaking of services, the formal delineation between industries and workers that “make things” and those that don’t “make things” has become increasingly meaningless (or, at least, artificial). Most obviously, tens of millions of Americans make “things”—buildings, transmission lines, solar panel installations, software, mRNA platforms, etc.—that are real and economically important but not considered a “manufactured good” and thus not counted among the “things” we make. (Humorously, baked goods and tortillas are, while accountants treat software as a tangible or intangible asset depending on how it’s used.)

Making houses or lines of code matters too, especially today, but a myopic focus on the production of physical goods not only ignores these industries but can, through tariffs and other policies that raise the domestic price of manufactured goods (e.g. computers) on which these other industries rely, actually hurt them. Digging into some of these bright lines can also produce absurd results. Cutting down a tree isn’t manufacturing; turning the log into lumber is manufacturing; driving the lumber to a homesite and then turning it into a house—nope, not manufacturing! (And, of course, tariffs on that lumber hurt all the non-manufacturing folks involved in making those houses.) Why the government should prioritize the second step here is unclear, at best.

Just as importantly, many services are often connected or integral to “actual” manufacturing—and increasingly so. Consider the rise of “factoryless” goods producers in the United States, which we discussed last year. Big, innovative U.S. companies like Nike or Nvidia are expressly in the business of “making things” like shoes or semiconductors, and they handle everything—design, R&D, marketing, etc.—except the final stage of production, which they’ve outsourced to other companies in the United States or abroad. These firms still employ lots of people, still make huge investments, still generate tons of economic output, and in many cases are important for national security. And their success is in large part based on their factoryless model. They matter too.

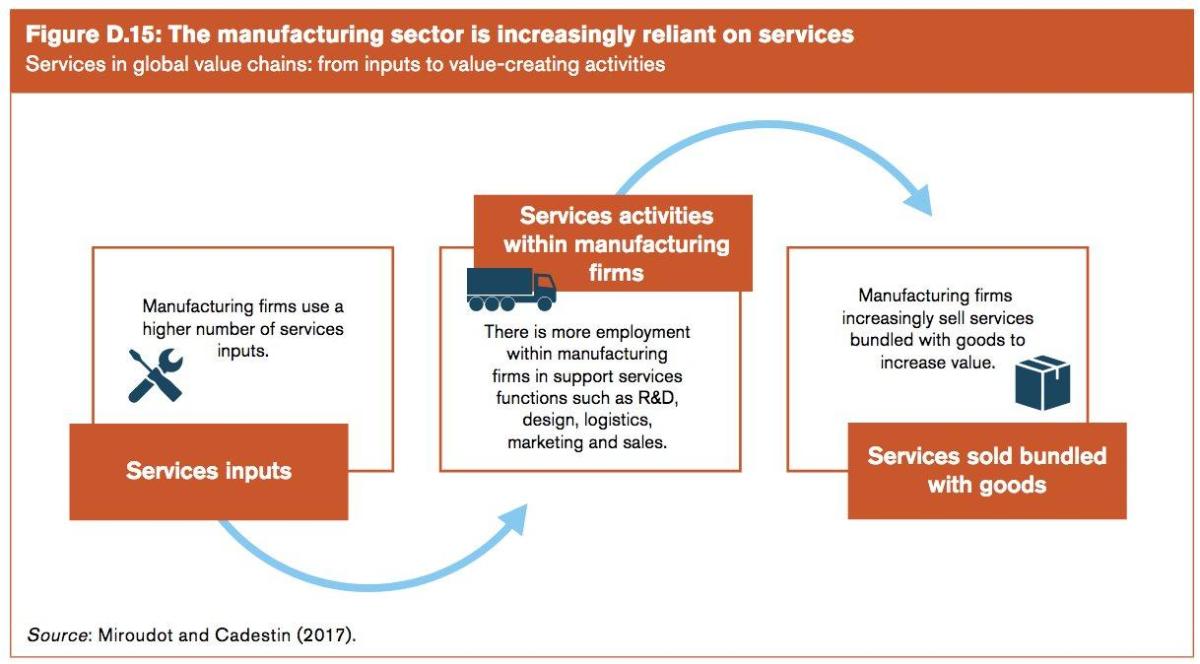

Meanwhile, many of the American companies that still own and operate factories are also increasingly incorporating services into core businesses. This “servitization of manufacturing,” Middlebury’s Gary Winslett explained in 2022, includes both the services that have traditionally complemented manufacturing—transportation, R&D, maintenance/repair, etc.—and relatively new ones like cloud computing, software, and 3D printing. At the same time, traditional manufacturers are increasingly reliant on both pre-production services inputs and post-production services bundled with their products (customer support, training, security, entertainment, upgrades, etc.).

In his paper, Winslett cites hearing aids a great example of how this new system works in practice—and its many benefits:

It was once the case that hearing aids were very labor-intensive to produce, relatively costly, not necessarily comfortable because they could not be customized for the user, and potentially embarrassing to the user since their size meant that they were difficult to hide within the ear canal. Then, in the span of just over a year in the mid-2000s, the industry underwent an enormous and rapid transformation; virtually the entire industry transitioned from traditional manufacturing to 3D printing. Now, a user would get their ear canal scanned by their audiologist, a digital copy of that scan would be used to create a specialized computer-aided design file for the shell of their hearing aid, and then that hearing aid would get produced and sent to them by the manufacturer, which in practice were typically located in Denmark and Switzerland, as the firms in those countries were early adopters of 3D printing. This switch to 3D printing allowed hearing aids to be customized for each user (thus reducing discomfort and stigma), improved the sonic quality of the hearing aid, and, at the same time, lowered costs by reducing the production process from nine steps to three. Because these hearing aids were both better and more affordable (due to the new servitization of the product), the international trade in them increased by 58% after the adoption of 3D printing. An analysis of thirty-five other products showed similar results suggesting that this was not an idiosyncrasy of hearing aids.

Manufacturing myopia would prioritize (and get upset about!) the Danish or Swiss “printing” the modern hearing aid and the United States importing it. That’s despite all the innovative, high-value U.S.-based services that went into the device’s overseas production and domestic use and all the incredible benefits this new system provided American hearing-aid users. It makes little sense.

But wait, there’s more. These newfangled services are often separate from and outsourced to other non-manufacturing companies, but other times they’re provided in-house by a U.S. manufacturer. Only the latter, however, will officially count as American “manufacturing” output and jobs, even though both approaches cover the exact same economic activity. Thus, one recent paper estimates that about 40 percent of “manufacturing employment” today is actually in services. It’s also why, as the Financial Times’ Gillian Tett explained in 2019, the “China Shock” to U.S. factory employment was in large part mitigated by American manufacturers hiring lots of workers … in services.

Between 1977 and 2012, the number of “manufacturing firm workers” employed in “manufacturing plants” halved from just under 20m to nearer 10m. However, the employees in “non‐manufacturing plants” that were owned by “manufacturing firms” rose from 13m to 23m, primarily due to an explosion in service sector jobs such as design and IT. As a result, by 2012 the US’s “manufacturing” companies employed slightly more workers than in 1977. Moreover, that was not because of business churn: 75 per cent of the “manufacturing” job losses in this period occurred at companies which remained in business, and it was the incumbents which opened most of the non‐manufacturing plants. In plain English, this means that as Chinese competition hit, America’s “manufacturing” groups quietly re‐engineered themselves. Yes, they might call themselves “manufacturers”, and be defined that way in the data. But they increasingly hire service‐sector workers, as their output soars.

All of this should hopefully show how the lines between “making things” and “not making things” have been blurred—and why policies like tariffs that target only physical goods are misguided at best and outright harmful at worst (taxing hearing aids!). Factoryless producers and American service providers supposedly don’t “matter” because they don’t make physical “things,” but go and attach an assembly line to the exact same companies and suddenly they do. As one recent paper on this topic explained, “historic policymaking divisions between trade in manufactures and trade in services, between export and import interests, and among modes of supply are becoming less relevant.”

Someone please tell our goods-obsessed policymakers.

And Services Can Be Great Too, By the Way

Finally, manufacturing mythology ignores all the economic value that services can provide, regardless of whether they’re connected to the production of physical goods. Beyond the fact that we mostly work in services and mostly consume services, and that economies everywhere gravitate toward services as they develop, services jobs can be just as good-paying (see above) and productive as manufacturing jobs, if not more so. As Grabow notes, a 2018 analysis from the International Monetary Fund “found that manufacturing does not play a unique role in productivity growth and that ‘some service industries [exhibit] productivity growth rates as high as the top‐performing manufacturing industries.’”

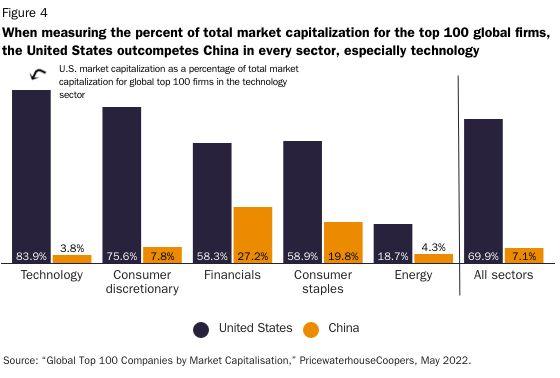

Many of the biggest and most innovative companies in the world, moreover, are primarily focused on services—a particular advantage for the United States (and one that we should be leaning into). Here, for example, are the largest companies in the world today by market capitalization, with Tesla as the only American company on the list that does much of its manufacturing in-house (and they do a lot of services too, by the way):

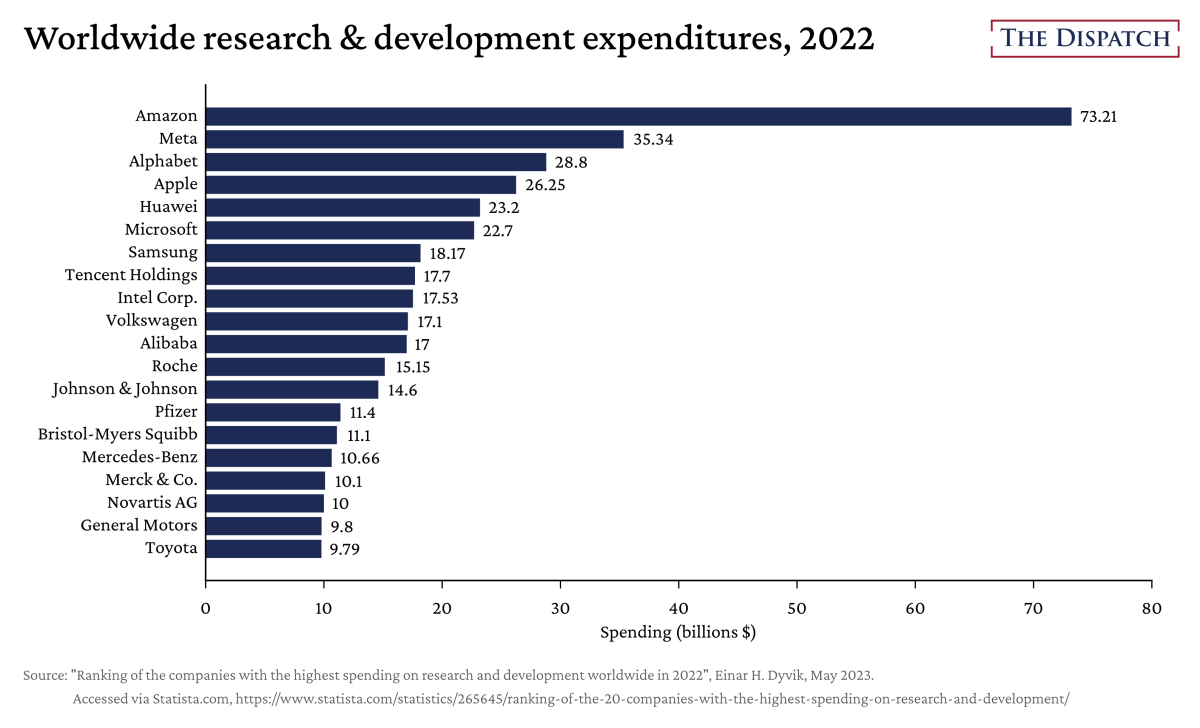

At the same time, four of the top six R&D spenders in the world in 2022 were U.S. companies primarily performing services (Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft), while fourth place on that list was Apple, which famously outsources much of its manufacturing (and performed more than $21 billion in services last year too):

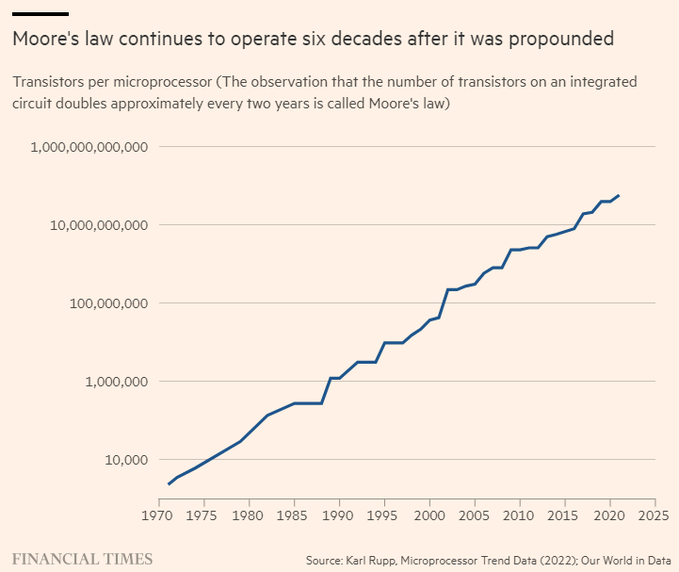

To get an idea of just how much these companies are spending, Wharton professor Ethan Mollick provides useful context on Twitter: “The R&D spending of Amazon is greater than the R&D spending of all companies and government in France. Alphabet beats Italy.” Factoryless chipmaker Nvidia, meanwhile, spent more ($7.3 billion) in 2022 than all of Mexico. And these investment trends aren’t exactly new, either. The Progressive Policy Institute reports that American tech giants (including broadband companies) were leading the U.S. investment charge before the pandemic, too. Other lists of the world’s most innovative companies, as we discussed last year, are also chock-full of U.S. services companies or manufacturers—factoryless or otherwise—heavily reliant on outsourcing physical production. (Only Tesla really stands out as the opposite.)

So much for the notion that, as some tariff fans still claim, “Technological innovation atrophies when it is separated from production.” It sure doesn’t look like it.

Finally, and as we’ve discussed, all this spending and innovation—particularly as it relates to generational technologies like artificial intelligence—is, along with U.S. companies’ (mainly in services!) economic heft, also geopolitically important:

In short, services matter too—a lot.

Summing It All Up

None of this means that manufacturing is bad or that the U.S. government should suddenly thumb the economic scale in favor of certain services. Instead, it’s an argument (technically, another one) against policies like global tariffs that treat the U.S. manufacturing sector as in dire need of broad-based, indiscriminate government support or protection, or that myopically advantage “making things” above all the other valuable economic activity that doesn’t happen to fit into that rigid, antiquated category (and, in fact, might actually support it).

We still make lots of “things” here in the United States, and many of the biggest and most important companies in the world are today in—or dependent on—services. Those are the facts, and no amount of protectionism or presumptuous sloganeering will change them.

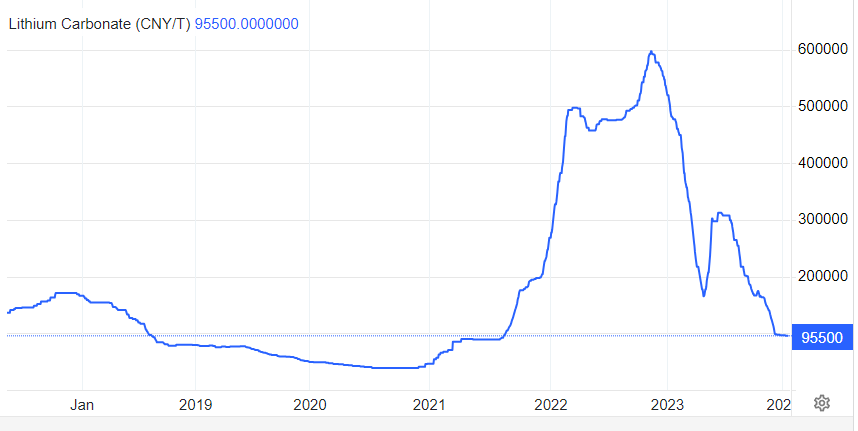

Charts of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.