When I think of 9/11, my memories come in a jumble. It’s like watching a trailer of a movie I’ve already seen. There was the shock of watching the second plane impact the World Trade Center’s south tower and the instant realization we were under attack. Then there’s smoke billowing from the Pentagon and a rush of rumors and reports that made us feel, for hours on end, that perhaps the attack was even worse and more widespread than it actually turned out to be.

The memories keep coming. There’s Congress singing “God Bless America” on the Capitol steps. There’s George W. Bush’s bullhorn moment at the rubble of the World Trade Center, and his first pitch at the World Series. It’s hard to even begin to describe the sense of national unity and purpose that arose instantly and spontaneously.

I can remember thinking, for a time, that this day was my generation’s Pearl Harbor, and this was my generation’s war. I felt deep regret that I was too old to join and do my part (little did I know I’d drag my even-older carcass through an officer basic course five years later—37 is not the ideal age to learn the low crawl.)

But it wasn’t Pearl Harbor, not even close. We should mainly be thankful (after all, Pearl Harbor marked the beginning of a far more deadly war), but the fact that it wasn’t Pearl Harbor is also the reason why that sense of national unity was always going to dissolve, quickly. It was so transient that it feels like a dream.

The quickest and easiest way to describe the difference between Pearl Harbor and 9/11 is to note the obvious reality that Pearl Harbor was but the opening attack in a comprehensive military campaign against American forces across a front thousands of miles wide—an attack that pulled the United States into an existential civilizational struggle that was already underway.

Even though the 9/11 attacks were arguably more destructive and certainly more deadly than the Pearl Harbor air raid, jihadists never presented an existential military threat to our nation, much less to western civilization. They could not follow up 9/11 with a campaign that remotely approached the ferocity of a superpower (like Japan) at war. If they faced us in battle, we were always going to swat them aside.

But stating the facts of our military superiority should not minimize our challenge. Though jihadists could never threaten our civilization, they could hurt us and hurt us badly. And if they hurt us enough, they’d change our nation in important and profoundly negative ways. There remained and remains an absolute necessity of national self-defense.

Moreover, despite the confident assertions of countless pundits, the best method of achieving that national self-defense was never obvious or easy.

There were conceptual debates—should we view the terrorist threat through a law enforcement lens or a military lens? Or both? (We chose both.)

There were tactical and strategic debates. Is the best counter-terror strategy one that looks more like whack-a-mole, trying to knock down threats individually as they emerge? Or is it more systemic, requiring us to take and hold ground and slowly but steadily generate more stable and just allied nations and governments that would not threaten our interests? (Again, we chose both.)

At the same time, however, our nation walked into the war conditioned by recent conflicts to expect immediate, overwhelming success. We braced for mass casualties in Desert Storm, and we rolled through Saddam’s Army (then one of the largest in the world) in roughly 100 hours of ground combat. We’d conducted aerial campaigns in the Balkans often without suffering a single combat loss.

And then Kabul fell so very quickly. Baghdad fell less than two years later with shocking speed. It all seemed easy—until it didn’t. And then we had no clear path. It was easy to forget that we never did.

In the Second World War we confronted immense challenges and terrifying casualties, but the fundamental, basic goal—defeating a nation-state in battle and imposing terms of peace—was familiar to the world and familiar to the United States.

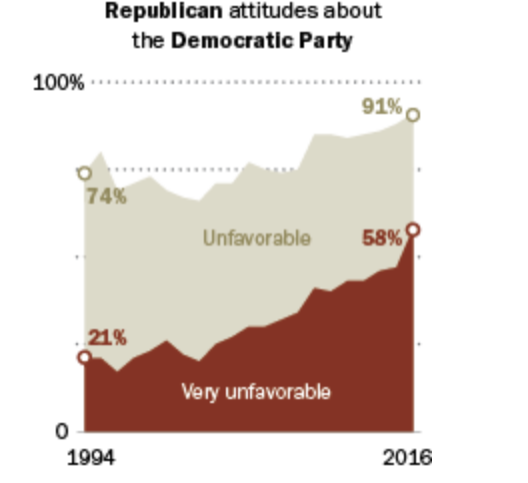

In the absence of the existential threat and the cloudiness of the strategic way forward, it was inevitable that our post-9/11 response would polarize Americans. Or, I should say, continue to polarize Americans. The trend that we now call “negative partisanship” or “negative polarization” was already well underway. I like these Pew charts, taken from 2016 (so that we can see how much Americans despised each other even before Trump won).

First, here are the Republicans:

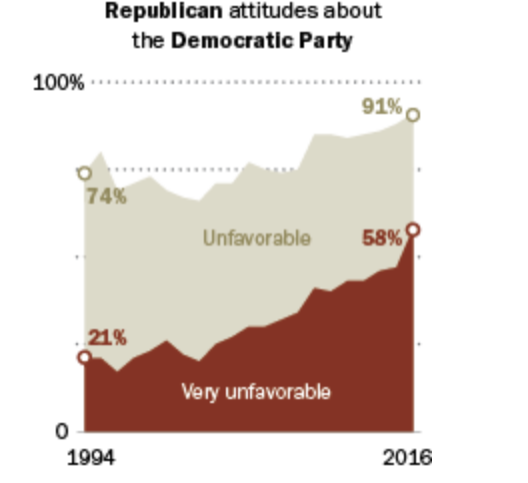

Did the Democrats feel much more warmth? Nope:

In my book, I argue that the triple crises of the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War created a period of both false national unity and necessary national consolidation. Existential economic, military, and ideological threats helped paper over domestic divisions (not entirely, of course, but substantially). The necessity of military victory in World War II and deterrence in the Cold War led to a massive standing military, something unusual in the American story.

In hindsight, it’s clear that the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of American global hegemony meant that we were going to revert to the messy fractiousness that’s marked much of American history and that’s typically going to mark a continent-sized, multi-ethnic, multi-faith democracy. As horrifying as 9/11 was, it could only call us back to our more unified selves for a very short period of time.

In short, we faced a challenge dangerous enough to command our attention, not dangerous enough to unite us, and complicated enough to defy easy, obvious answers.

(Lest you think one obvious alternative path was “never invade Iraq,” it is fairly easy to spin out a number of terrible scenarios had Saddam Hussein retained his power, and we know from the genocidal war next door in Syria that a strategy that largely leaves dictators to their own devices has its own profound and destabilizing risks.)

Given this reality, it is remarkable that we have fought so very long. But that’s mainly because most Americans could easily shove the war out of their minds. Not only were casualties low by historic standards, we never came close to instituting a draft.

The men and women who fought and bled and died were often double or even sometimes triple volunteers. They volunteered to put on the uniform. They often then also volunteered to join combat arms. Sometimes they also volunteered specifically to deploy. Then, once in country, they’d often volunteer time and again for missions that could feature an absurd amount of risk.

So we were left with a war that was politically contentious but psychologically sustainable. Except for the weeks immediately after 9/11, we never fully felt like a nation at war. I’ll never forget coming home for mid-tour leave, landing in the Atlanta airport, walking through the terminal with Iraqi sand still on my boots, looking at everyone and thinking, “They have no idea what it’s like. They’ll never have any idea.”

I’m not sure how I’m going to feel this Saturday, on the 9/11 anniversary itself. I know that I’ll think about the families of the victims. I’ll think about the men and women who’ve lost lives and limbs in the long struggle since that dreadful day. And I find myself mainly unimpressed by many of the takes about the larger meaning of America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, that it somehow signifies an “empire in decline.”

I opposed withdrawal, but I’ll be honest—we sustained the fight longer than I thought we would. Our military isn’t exhausted or worn down by the fight. It retains its immense strength. We experienced failures in leadership, yes, but failures of command are not invariably indicators of national decline. On that score, the geopolitical crises of the late 1970s were far more grave than the crises we face today.

At the end of the day, however, for all the failures we rightly lament, I can perhaps look to the World Trade Center site itself to properly frame my profoundly mixed feelings.

The 9/11 memorial helps us remember the attack and mourn its victims. The Freedom Tower, however, reminds us that our nation is resilient, it can still build magnificent things, and for all divisions and challenges, we have succeeded in one central national goal—we have kept our nation safe. The 9/11 attack remains a singular crime. It has not happened again.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.