A note to our readers: This edition of the French Press went to paying members on Tuesday. It’s an important message about politics and the media, and we wanted to share it with you. Thank you for reading.

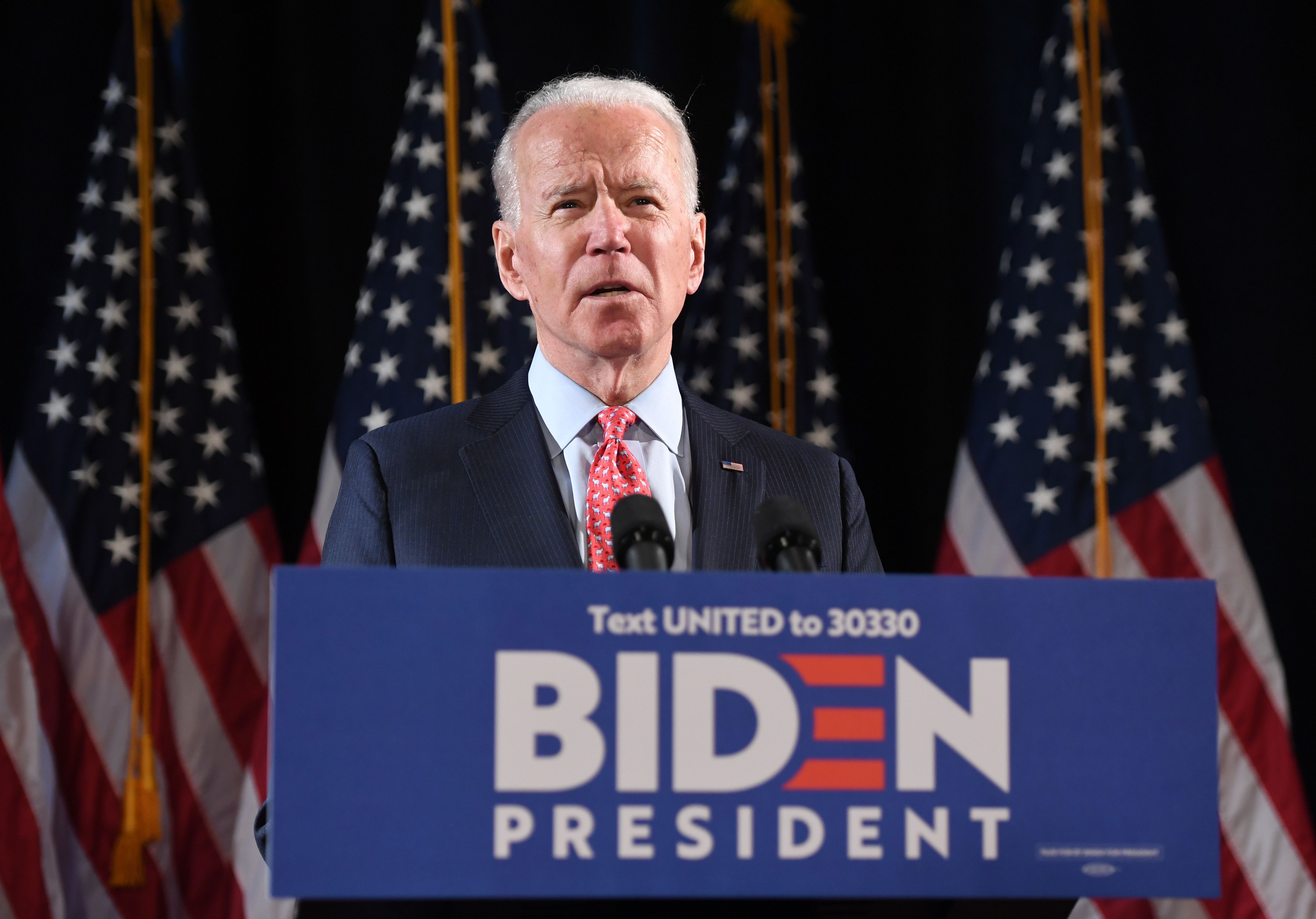

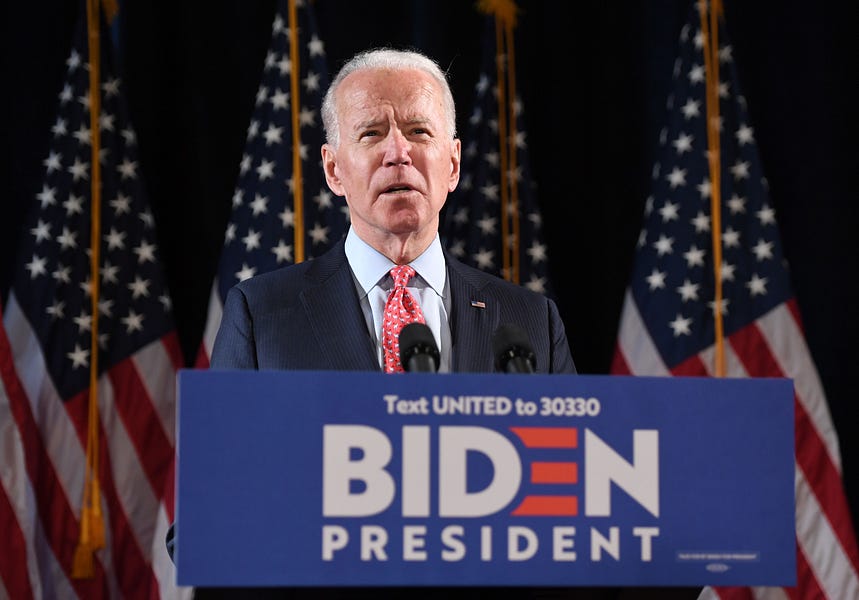

The first public sexual misconduct claim I ever evaluated was Anita Hill’s sexual harassment claim against Clarence Thomas. I was in law school, locked into the daily classroom battles with my fellow students and professors, and I dove deep into the details. After Clarence Thomas, the names of accused politicians are simply too many to remember. The big names stand out—Bill Clinton, Bob Packwood, Anthony Weiner, Eliot Spitzer, Donald Trump, Roy Moore—and now Joe Biden, former vice president and presumptive Democratic nominee for president.

Over the course of more than two decades, I’ve developed a simple test for these claims: If the weight of the available evidence indicates that it is more likely than not that the allegations are true, then the accused should not hold high office. Requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt is imprudent. After all, no person possesses a right to public office, and requiring such a high standard of proof would create a perverse permission structure for bad acts.

But lower burdens of proof are dangerous as well. We frequently hear politicians and pundits use phrases like “credibly accused.” What does that even mean? There are plenty of questionable statistics that claim only the smallest fractions of women make false accusations, but our legal system doesn’t adjudicate innocence but merely burden of proof. The percentage of false claims is unknowable, and as a result, almost any accusation can be subjectively deemed “credible” absent slam-dunk evidence of innocence.

Perhaps my mindset is influenced by more than two decades of litigation (including work on multiple sexual harassment cases), but when I review sexual misconduct claims, I ask myself, “Based on the available evidence, is this a case I’d feel comfortable taking to a jury?”

The things that influence the analysis include the age of the allegation, presence or absence of contemporaneous corroboration, presence or absence of conflicting or supporting evidence, consistency of the claimant’s story, evidence of a pattern of behavior, and evidence of bias. That’s not a complete list, but it’s exactly how lawyers make decisions whether to bring cases, and that’s how juries make decisions about guilt or liability.

Applying these factors to Brett Kavanaugh illustrated the profound weakness of the claims against him. Each claim was more than 30 years old. There was no meaningful contemporaneous corroboration. Christine Blasey Ford’s friend couldn’t even place Ford and Kavanaugh together at the same party. According to her therapist’s notes, there was evidence that Ford had given materially conflicting accounts about the alleged assault. Yes, lots of folks found her demeanor credible when she offered live testimony, but spend five minutes in a courtroom and you’ll quickly understand that “demeanor” is one of the least reliable indicia of truth.

When you apply the factors above to many of the sexual assault and sexual harassment claims against Donald Trump, one reaches a different outcome. Many of the claims are supported by contemporaneous corroboration, they fit a specific pattern, and Trump himself has openly bragged about grabbing women by the genitals. While not every claim is credible, enough are that I feel quite comfortable arguing that it is more likely than not that Donald Trump is guilty of sexual harassment at best and sexual assault at worst.

What does this mean for former Biden staffer Tara Reade’s claims against him? After days of Twitter talk and a number of articles in progressive publications, the Washington Post and New York Times finally published lengthy, detailed reports of Reade’s claims. The reports were careful and comprehensive, and they revealed a case that—on the merits—is stronger than the case against Kavanaugh but not strong enough (in my view) to make her accusation likely true.

At the same time, however, the prestige media’s care in reporting the claims against Biden stood in very stark contrast to its conduct in the Kavanaugh confirmation fight.

Let’s deal with Reade’s claims first. Make no mistake, she alleges criminal sexual assault. Here’s the Times’s summary:

The former aide, Tara Reade, who briefly worked as a staff assistant in Mr. Biden’s Senate office, told The New York Times that in 1993, Mr. Biden pinned her to a wall in a Senate building, reached under her clothing and penetrated her with his fingers. A friend said that Ms. Reade told her the details of the allegation at the time. Another friend and a brother of Ms. Reade’s said she told them over the years about a traumatic sexual incident involving Mr. Biden.

If this is likely true, it should be disqualifying—at least in a healthy political culture. Moreover, Reade claims that she told other people about the incident at the time and some years later:

A friend said that Ms. Reade told her about the alleged assault at the time, in 1993. A second friend recalled Ms. Reade telling her in 2008 that Mr. Biden had touched her inappropriately and that she’d had a traumatic experience while working in his office. Both friends agreed to speak to The Times on the condition of anonymity to protect the privacy of their families and their self-owned businesses.

Ms. Reade said she also told her brother, who has confirmed parts of her account publicly but who did not speak to The Times, and her mother, who has since died.

On this score, she has more supporting evidence than Ford had against Kavanaugh. No one disputes that Reade worked for Biden, and none of Ford’s witnesses could offer any evidence that she told them of the alleged attack at the time.

There is, however, a lot that’s odd about the story. The Washington Post’s account details the troubles with her account quite well. First, she’d made previous claims against Biden before without mentioning an assault:

In interviews with The Post last year, Reade said that Biden had touched her neck and shoulders but did not mention the alleged assault or suggest there was more to the story. She faulted his staff, calling Biden “a male of his time, a very powerful senator, and he had people around saying it was okay.”

Second, her brother’s account isn’t consistent:

In another recent interview, Reade’s brother, Collin Moulton, said she told him in 1993 that Biden had behaved inappropriately by touching her neck and shoulders. Their mother urged Reade to contact the police, Moulton said, adding that he felt “ashamed now for not being a better advocate” for his sister. Several days after that interview, he said in a text message that he recalled her telling him that Biden had put his hand “under her clothes.”

Third, while Reade claims she made a harassment complaint against Biden, no other evidence of the complaint exists and Biden’s team denies receiving any complaint.

Fourth, in interviews last year, she seemed to exonerate Biden for alleged harassment, claiming problems with his staff:

In The Post interview last year, she laid more blame with Biden’s staff for “bullying” her than with Biden.

“This is what I want to emphasize: It’s not him. It’s the people around him who keep covering for him,” Reade said, adding later, “For instance, he should have known what was happening to me. . . . Looking back now, that’s my criticism. Maybe he could have been a little more in touch with his own staff.”

Finally, there seems to be no similar allegation against Biden. There are no claims of troubling patterns of behavior beyond the excessive touching and nuzzling that’s been on public display for decades.

Some of Biden’s defenders have zeroed in on her support for other candidates, but as my colleague Sarah Isgur pointed out in yesterday’s Advisory Opinions podcast (subscribe!), of course she’s not going to support the man she claims assaulted her.

Biden’s defenders have also zeroed in on Reade’s rather effusive praise for Vladimir Putin (she once called him a “compassionate, caring, visionary leader”). I don’t find her regard for Putin all that relevant to her claims against Biden.

At the end of the day, however, we’re left with a 27-year-old claim with a single anonymous corroboration that’s inconsistent with the claimant’s own previous accounts and is (so far) unsupported by any other claim of similar behavior. I’m troubled but unconvinced. Based on the current state of the evidence, I don’t think it’s likely that Biden assaulted Reade.

I am convinced, however, that large segments of the media are guilty of a shocking double standard. The care they took to deliberately report out Reade’s claims stands in stark contrast to the behavior of some of these same outlets during the Kavanaugh confirmation battle.

Let’s be precise—I do not have a problem with the Post’s initial report on Christine Blasey Ford’s claims. She had contacted the paper months before, and when you read the report, it clearly shows that the Post did considerable homework. In my first evaluation of the claims, I wrote that the age of the claims, the lack of any pattern of behavior, the lack of corroboration, and the contradictory evidence in her therapists’ notes made her claims “serious but not solid.”

In short, I thought the Post did a good job on the report. But we all know the reporting and analysis did not stop there. Writing in The New Yorker, Jane Mayer and Ronan Farrow published the completely unsubstantiated claim that Kavanaugh exposed himself to a woman named Deborah Ramirez. Not only did she confess to drinking heavily and to memory gaps, she said that she only came forward “after six days of carefully assessing her memories and consulting with her attorney.”

Even worse, The New Yorker stated that the magazine “has not confirmed with other eyewitnesses that Kavanaugh was present at the party.” (Emphasis added.) That’s extraordinary. The claim never should have made it to print, but not only did it reach The New Yorker’s prestigious pages, but virtually every other prestige media outlet carried the claims immediately.

But the negligence surrounding Ramirez’s claims is nothing compared to the widespread press negligence and outright recklessness in reporting Michael Avenatti client Julie Swetnick’s fantastical and grotesque claims that she saw Kavanaugh “waiting his turn” for gang rapes after facilitating them by spiking or drugging the punch at high school parties. The mainstream media reporting on the claim was immediate and prominent. On Twitter, journalist after journalist immediately credited her claims.

To be fair, some of that mainstream media reporting (especially at the Wall Street Journal and a damaging MSNBC interview) was important in quickly debunking Swetnick’s claims, but unlike Reade’s claims against Biden, they immediately entered the media bloodstream.

Unquestionably, Biden received better treatment than Kavanaugh. To its credit, the New York Times has now questioned itself about the disparity. Ben Smith interviewed executive editor Dean Bacquet, and I’d urge you to read the entire exchange. Two answers stand out. Here’s the first:

I’ve been looking at The Times’s coverage of Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh. I want to focus particularly on the Julie Swetnick allegations. She was the one who was represented by Michael Avenatti and who suggested that Kavanaugh had been involved in frat house rapes, and then appeared to walk back elements of her allegations. The Times wrote that story the same day she made the allegation, noting that “none of Ms. Swetnick’s claims could be independently corroborated.”

Why was Kavanaugh treated differently?

Kavanaugh was already in a public forum in a large way. Kavanaugh’s status as a Supreme Court justice was in question because of a very serious allegation. And when I say in a public way, I don’t mean in the public way of Tara Reade’s. If you ask the average person in America, they didn’t know about the Tara Reade case. So I thought in that case, if The New York Times was going to introduce this to readers, we needed to introduce it with some reporting and perspective. Kavanaugh was in a very different situation. It was a live, ongoing story that had become the biggest political story in the country. It was just a different news judgment moment.

I’m sorry, but it’s difficult to be more in a “public forum in a large way” than by emerging as the Democratic frontrunner for president. Moreover, one of the reasons why the “average person” didn’t know about Tara Reade was because organizations like the New York Times weren’t covering it. The Times helps establish what the average person knows.

Second, read this:

I want to ask about some edits that were made after publication, the deletion of the second half of the sentence: “The Times found no pattern of sexual misconduct by Mr. Biden, beyond the hugs, kisses and touching that women previously said made them uncomfortable.” Why did you do that?

Even though a lot of us, including me, had looked at it before the story went into the paper, I think that the campaign thought that the phrasing was awkward and made it look like there were other instances in which he had been accused of sexual misconduct. And that’s not what the sentence was intended to say.

At the risk of stating the obvious, one does not establish and maintain a reputation for editorial independence by making changes in news stories because a partisan political campaign “thought that the phrasing was awkward.” It’s awkward, or it’s not, and if a change is made it should not be a stealth edit (as it was in the original report).

As Sarah argued in our podcast, pointing out the media double standards should not mean that the Kavanaugh standard should become the norm. Instead, the patient deliberative thoroughness of the Biden reports (and the initial Washington Post Roy Moore report, for that matter) represents a far better practice. And that practice should be bipartisan—no matter how loudly the Twitter mob howls.

One last thing …

Sigh. Some days the loss of the NBA hurts more than others. This is one of those days. So to ease our pain, let’s remember a great night in a great season for the most lovable team in the NBA:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.