I must confess that there are times—not often—when I regret hanging up my litigation spurs. I’ve seen first-hand what a comprehensive national litigation strategy can do to reverse illiberal or authoritarian trends. For example, when a merry band of First Amendment litigators first began to take on university speech codes (speech policies that unlawfully restrict constitutionally protected expression), more than 70 percent of major colleges and universities maintained so called “red light” speech codes, according to the nonpartisan Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE).

(Full disclosure, I’m a former FIRE president, and I helped launch its first efforts to evaluate university speech policies.)

By 2021, the “red light” schools had dropped to 21 percent, and a record number of schools earned the “green light” endorsement—indicating that their policies “do not seriously threaten campus expression.”

Why did this happen? The answer is complicated, involving a series of state campus free speech laws, internal campus political dynamics, and a wave of federal speech code lawsuits. But I’m convinced that litigation was the precipitating event that forced change. Simply put, universities kept losing and losing lawsuits. In fact, no university has ever won a speech code challenge on the merits. The policies were a legal disaster, and schools collectively paid millions of dollars in legal fees after mounting fruitless and futile defenses to clearly unconstitutional policies.

Why bring this up? Because it just might be time for an equivalent effort aimed at the most illiberal and hyper-woke elements of critical theory in the workplace, in academia, and in the media. It is increasingly clear that many elements of modern academic and workplace orthodoxy (including punitive actions) are incompatible with the plain text and obvious meaning of federal civil rights laws.

Without diving too much into the weeds of all the complex and interlocking state and federal civil rights laws, there are three federal civil rights statutes that govern much of modern American academic and workplace life.

The first, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibits workplace discrimination on the basis of “race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.” Thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, Title VII also protects employees from being fired “merely for being gay or transgender.”

The second, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, states that “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

The third, Title IX of the Education Act of 1972, protects people from sex discrimination in language that’s nearly identical to the race discrimination prohibition of Title VI.

Taken together, these statutes provide extraordinarily broad protections for discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion (and now LGBT status) across an immense range of public and private organizations in the United States. These statutes have been upheld against constitutional challenge in a variety of contexts, and they represent the very paradigm of “settled law” in American civil rights jurisprudence.

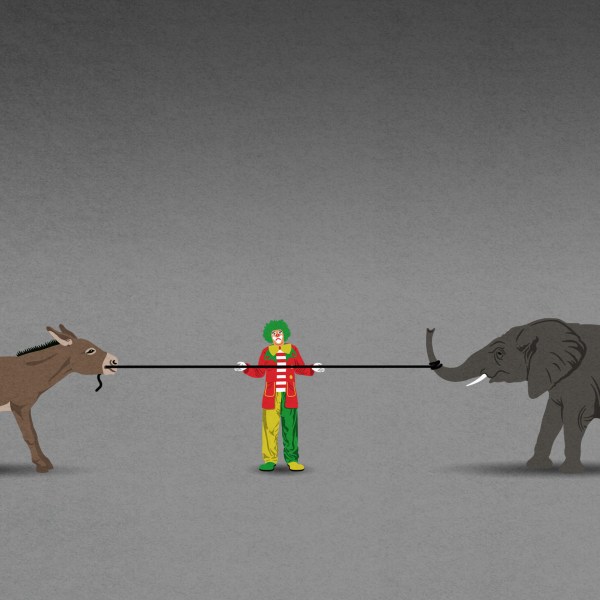

Now, sitting across the figurative deposition table from this trio of laws is a brand of far-left identity politics that increasingly centers on race, sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation in ways heretofore relatively unseen in the American workplace.

I’m not arguing that federal civil rights statutes require race blindness. For example, the Supreme Court has long upheld voluntary affirmative action programs in the workplace, and the EEOC provides comprehensive guidance on establishing and maintaining lawful affirmative action plans. Nor do civil rights statutes prohibit diversity training designed to teach the value of diversity and inclusion.

But it is also true that civil rights statutes protect Americans of every race and both sexes. There is ample precedent for the notion that Title VII, for example, protects white employees from so-called “reverse discrimination.” Neither the legacy of past discrimination against people of color nor its distressing present persistence creates a free-fire zone against “whiteness” or against white employees.

Let’s take a look at some recent viral stories, beginning with Michael Powell’s outstanding reporting on an alleged racial incident at Smith College. In brief, a black student claimed that she was subjected to an intimidating encounter with campus security and a campus janitor because of her race. A university-backed investigation found the claim meritless. Despite the lack of evidence supporting the black student’s claims, members of the campus community were subjected to intrusive forms of “anti-bias” training:

Ms. Blair and other cafeteria and grounds workers found themselves being asked by consultants hired by Smith about their childhood and family assumptions about race, which many viewed as psychologically intrusive. Ms. Blair recalled growing silent and wanting to crawl inside herself.

The college also set up “white accountability” groups, and its overall conduct raises a serious question as to whether it engaged in hostile environment harassment on the basis of race as part of its effort to root out the alleged pernicious effects of “whiteness.”

I’d also urge readers to dive into former New York Times reporter Donald McNeil’s four-part Medium post regarding his forced resignation from the Times after he said the N-word on a Times trip with students. He did not use the word as a slur but instead quoted it in the context of a discussion about the propriety of its use.

The posts raise a host of questions about the fundamental fairness of the Times’s disciplinary proceedings and about the ideological intolerance of a substantial portion of the Times newsroom. But as I read the posts, it struck me that McNeil may well have a Title VII complaint against the paper. Is it really the case that the Times can maintain a double standard about the use of certain words based entirely on the race of the speaker?

(To be sure, the Times can prohibit the use of racial epithets as slurs. But we’re discussing the mention of the word, not its use as a personal attack.)

Moreover, there are two unfolding legal developments that may well render federal civil rights law even more potent in defending against far-left or “woke” forms of discrimination. The first I mentioned above: the Bostock decision. In Bostock, the Supreme Court held that Title VII’s prohibition on sex discrimination also protected gay and transgender employees. Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion came under heavy fire from conservatives as an example of “sloppy” textualism. Yet I wonder if folks on the left who cheered the outcome understood the full meaning of Gorsuch’s opinion.

Summed up in one sentence, it would be this: The intent of the drafters does not matter. “Sex” means “sex,” and if adverse (harmful) job action takes place even in part because of sex, it’s unlawful. Here’s Gorsuch:

An employer violates Title VII when it intentionally fires an individual employee based in part on sex. It doesn’t matter if other factors besides the plaintiff’s sex contributed to the decision. And it doesn’t matter if the employer treated women as a group the same when compared to men as a group. If the employer intentionally relies in part on an individual employee’s sex when deciding to discharge the employee—put differently, if changing the employee’s sex would have yielded a different choice by the employer—a statutory violation has occurred. Title VII’s message is “simple but momentous”: An individual employee’s sex is “not relevant to the selection, evaluation, or compensation of employees.”

And now, a cert petition was just filed in an important case that asks simply, does “race” mean “race”? The case is Students for Fair Admission v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, and the plaintiffs allege comprehensive anti-Asian discrimination at virtually every stage of the Harvard admissions process. Every race was privileged over Asians, and the result is that Asian students had to clear higher hurdles for admission than any other student from any other ethnic background.

Lower courts have rejected the plaintiffs’ claims, but given the strength of the evidence (and the Court’s ongoing efforts to wrangle with race-conscious admissions policies), there is a solid chance that the Supreme Court accepts review. If it does, expect a seismic level of alarm from educational institutions that have long put a race-based thumb on the college admissions scales.

The bottom line is clear: The more that courts ban all forms of sex discrimination or all forms of race discrimination that actually harm members of a protected class, the less room exists for explicitly race- or sex-conscious workplace or academic policies that are designed from the ground-up to be punitively race-conscious and/or punitively racially discriminatory. There should be, for example, no room in Title VII or Title VI for attacks on “whiteness” or harmful (invidious) discriminatory treatment of any racial group.

The distinctions are often a matter of common sense. It’s one thing to engage in diversity training that celebrates the benefits of inclusion. It’s another thing to teach a segment of your employees that their race or ethnicity is inherently laced with toxicity. It’s one thing to engage in affirmative action hiring designed to ameliorate documented past racial discrimination. It’s another thing entirely to impose rigid, higher standards on a different racial minority to limit their advancement or to impose different disciplinary standards on employees by race or sex.

Moreover, successful litigation has a prophylactic effect. It’s not as if litigation has to be won employer by employer. A few successful suits can set an example for the whole. During my litigation career, we sued dozens of universities, yet hundreds adjusted their policies.

The bottom line is clear. The more that hyper-left and hyper-woke policies and practices divide employees and students into distinct identity groups, and the more they enforce workplace policies and practices on the basis of those group differences, the more those policies and practices will collide with the plain language of federal anti-discrimination statutes—at the exact moment that the plain language is growing more important in the interpretation of statutory law.

Or, to put it more plainly: The most pernicious elements of critical theory or intersectionality may soon run up against a textualist litigation buzzsaw. In the battle between theory and text, bet on the text to prevail.

And another thing …

Last week the Supreme Court heard an important case regarding the ability of the police to enter your home while in “hot pursuit” of a suspect, even when the suspect has only allegedly committed a misdemeanor. Is your home your castle? Not always. Sarah and I had a fun debate. Listen here:

One more thing …

Last night I was minding my own business, preparing to watch Peaky Blinders (great show, by the way), when my Twitter timeline lit up. Tucker Carlson was insulting me and lying about me on live television. Normally I don’t respond to ridiculous personal attacks, but when they’re in prime time on the most-watched cable news show in America, I can’t stay silent. My response is below:

One last thing …

Whenever the online hate ratchets up, I find myself looking for respites from toxic polarization. This song, from SNL, should inspire and unite us all:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.