I thought—after federal officials let Jeffrey Epstein kill himself in prison—that I could no longer be shocked by incompetence. Yet, here I am, the day after the Iowa caucuses, shocked again. Also today, some thoughts on how Twitter creates its own reality, and we can’t do anything to stop it. Today’s French Press:

-

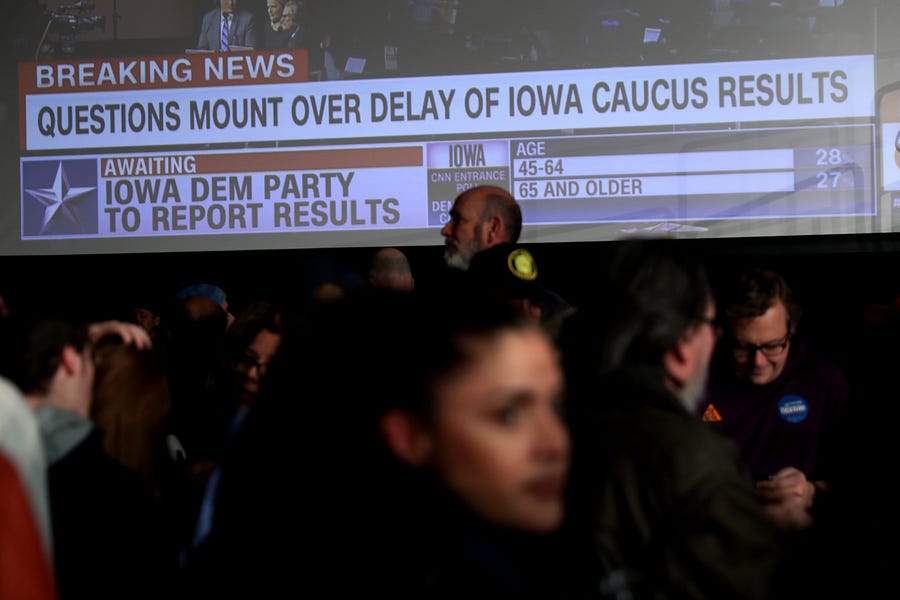

Iowa’s meltdown is a perfect representation of a true national challenge.

-

The human reason Twitter (or something like it) will always have too much influence.

Competence is patriotic.

If you follow my writing at all, you know that I think that policy is far less consequential to American life than culture. Now, that doesn’t mean at all that politics or policy are irrelevant or that they don’t influence culture to some extent, but if we’re weighing the relative importance of American culture versus American policy to the health of the nation, our culture is far, far more consequential.

And here’s a cultural reform of great potential consequence—let’s make America competent again. As I type this newsletter, we still have no official results from the Iowa caucuses. And the story of the meltdown is simply excruciating. Here’s how the New York Times begins its account:

DES MOINES — Sean Bagniewski had seen the problems coming.

It wasn’t so much that the new app that the Iowa Democratic Party had planned to use to report its caucus results didn’t work. It was that people were struggling to even log in or download it in the first place. After all, there had never been any app-specific training for this many precinct chairs.

So last Thursday Mr. Bagniewski, the chairman of the Democratic Party in Polk County, Iowa’s most populous, decided to scrap the app entirely, instructing his precinct chairs to simply call in the caucus results as they had always done.

The only problem was, when the time came during Monday’s caucuses, those precinct chairs could not connect with party leaders via phone. Mr. Bagniewski instructed his executive director to take pictures of the results with her smartphone and drive over to the Iowa Democratic Party headquarters to deliver them in person. She was turned away without explanation, he said.

The app didn’t work. The phones failed. The county couldn’t even deliver the results in person. And then, compounding the errors, the Iowa Democratic Party couldn’t clearly explain what went wrong. David Axelrod’s tweet was blunt and absolutely correct:

The Iowa Democratic Party will eventually announce the winner, and we’ll shortly move on from this moment—after all, the State of the Union is tonight, the Senate impeachment vote is Wednesday, and the New Hampshire primary is next Tuesday. Also, how many people even remember the 2012 Iowa GOP caucus? The party announced the wrong winner on caucus night, reversed itself days later, then held a convention where the candidate who came in third seemed for a time to secure the most delegates. Yes, there was that much confusion.

But let’s back up for a moment and imagine an alternative history of the United States. In this alternative history, we simply ask what would be different if American politicians, journalists, election officials, bureaucrats, and captains of industry were simply better at their jobs—in matters large and small.

What are the ripple effects if Palm Beach County election officials designed a less-confusing ballot for the 2000 election? How does America change if our intelligence agencies were more accurate in their assessment of Saddam Hussein’s chemical and nuclear weapons programs? Or, if we still failed on that front, how is our nation different if military and civilian leaders had not made profound mistakes at the start of the Iraq occupation?

We can do this all day. Let’s suppose for a moment that industry experts were better able to gauge the risks of an expanding number of subprime mortgage loans. . Would we be more trusting of government if it could properly launch a health care website, the most public-facing aspect of the most significant social reform in a generation? How can we accurately judge foreign threats if ISIS is dubbed a “jayvee team” the very year that it explodes upon the world stage and creates the largest jihadist state in modern history?

The ripple effects of incompetence are staggering. It’s easy to mislabel or misunderstand it as malice, especially when a person feels the sting of its consequences. And when the incompetence is particularly egregious, conspiracy theories can flourish. I mean, are we supposed to believe that federal officials wouldn’t keep close watch on the most famous prisoner in the entire federal prison system? Really? At a time when the media is reporting establishment Democratic alarm at the rise of Bernie Sanders, are we supposed to believe that the abject failure of that same establishment when Bernie is on the cusp of a potentially game-changing victory is entirely accidental and innocent? Really? Even after 2016?

In a time of negative polarization, “they can’t do their job” turns into “they hate me” and—ultimately—“their job is to screw me over.”

America will never be free of mistakes, and the more difficult and complex the job, the greater the likelihood of confusion and failure. But perhaps America’s political and journalistic class needs a bit of a course correction—instead of measuring virtue by ideas and intentions, let’s place a greater emphasis on execution and accountability. No one is entitled to a job. No state is entitled to its premier position in presidential primary contests. Incompetence has consequences, and those consequences should not be borne exclusively (or, if possible, even primarily) by its victims.

Why Twitter remakes the real world.

On Monday, the Pew Research Center published the results of a survey that demonstrated (once again) that Democrats on Twitter aren’t quite like Democrats off Twitter, and the differences can be striking:

The 29% of Democrats who use the platform are more liberal and less inclined to say the party should elect a candidate who seeks common ground with Republicans than are Democrats who are not on Twitter. They also express different preferences for who should be party’s 2020 nominee.

A 56% majority of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents who use Twitter describe their political views as liberal or very liberal. This share is substantially larger than the 41% of non-Twitter Democrats who describe themselves in this way.

Pew’s findings are similar to the data from a Hidden Tribes project, published last April. The evidence is overwhelming: Democrats who post political content to social media are far more progressive than Democrats who don’t.

In theory, these facts should help people on both sides of the aisle chill out about Twitter drama. No, it doesn’t reflect the American consensus. No, the rest of the world isn’t as extreme. Yes, its fights are here today, gone tomorrow. And yes, if you put down your phone and interact with people in the physical space, most of them won’t care one bit about anyone’s ratio.

But there’s a vast and yawning difference between an intellectual understanding and an emotional reality. The intellectual understanding—my ratio doesn’t matter—conflicts with the very human emotional response to actual words from actual people. It’s an online replica of a reality we see in the real world. Only a small, motivated fraction of parents can show up for school board meetings and exercise disproportionate influence. A small, motivated, group of protesters can take over a university administration building and turn the course of an entire institution.

Motivated minorities exercise outsized influence when they can get up-close and personal, and Twitter puts motivated minorities directly in your face, at scale, on a daily basis.

And, I’m sorry, you can say it’s “just Twitter” all you want—until the moment you’re the focus of Twitter outrage—or even the focus of mere Twitter attention. You can think you’re prepared for it. But if you’re a normal human being with a normal range of emotional responses to personal attacks, it’s jolting. For some people, it’s shattering. Unless you remake the human psyche from the ground up (or until you become accustomed to the abuse), it will always be jolting. It will always break some people.

Why do corporations capitulate so quickly to Twitter mobs? In part because key leaders may be ideologically sympathetic to the complaints, but also in part because the attacks quite simply hurt. There is an immediate pain-avoidance instinct that takes wisdom, perspective, and (quite often) practice to suppress. Thus, huge institutions can be pushed to move quickly before anyone in the offline world is aware there’s even a controversy.

Corporations are sometimes cowardly. There are times when the pressure is so slight that you can’t believe anyone caved. But more often institutions respond because they’re full of normal human beings, and normal human beings hate to be mocked and vilified. Because of this simple fact, Twitter (and the rest of social media) will always punch above its “true” cultural weight. It will always remake the real world.

One last thing …

Rarely does one 30-second spot combine two of my absolute favorite things. As a fan of fine cinema, I of course love the Fast and Furious franchise. Combine an ad for the new film with the greatest Gospel song of this generation (Kanye’s “Selah,” of course), and I’m all in. See you opening night!

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.