Hey,

Politics is full of dumb clichés: “The only poll that matters is on Election Day.” “It will all come down to turnout.” “I’m stepping down to spend more time with my family.” And relatedly, “I wasn’t having an affair, I was just doing constituent service [in that hotel room].”

One of the oldest is “politics makes for strange bedfellows.” Before I go on with the rank punditry, let me make a deeper point. There’s some profound—and profoundly valuable—wisdom in that line. To listen to many political combatants, the forces of good and evil are frozen in place for all time. Political uniforms can’t be shed, for they are tattooed on our souls. But the truth is that if political alliances can shift, that means political categories aren’t nearly as permanent or existential as we tell ourselves. Coalitions shift, interests change, parties rise and fall. The future is unwritten, so stop with your apocalyptic caterwauling already.

I can’t find the origin of the phrase “politics makes strange bedfellows.” But everyone seems to agree that it’s a rewording of a line from Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

The line is spoken by Trinculo, who, shipwrecked, wakes up next to what appears to be a fish-eyed monster named Caliban.

Legged like a man and his fins like arms! Warm o’ my troth! I do now let loose my opinion; hold it no longer: this is no fish, but an islander, that hath lately suffered by a thunderbolt. Alas, the storm is come again! my best way is to creep under his gaberdine; there is no other shelter hereabouts: misery acquaints a man with strange bed-fellows. I will here shroud till the dregs of the storm be past.

No doubt many a poor soul who had too many Jägermeister shots at a Tulane fraternity party know that feeling.

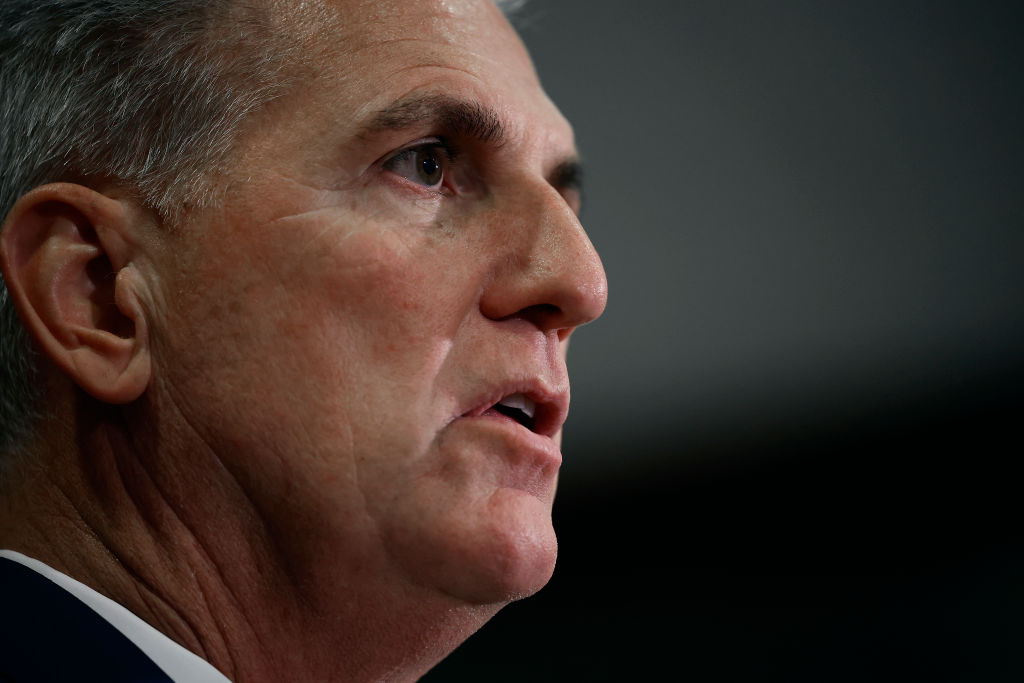

And so, too, might Kevin McCarthy. For now, he’s the presumptive next speaker of the House. Of course, McCarthy’s problem is that he won the election within the House GOP caucus, but he can actually get the job only if he gets a majority of the whole House. Technically, that’s 218 members—though it doesn’t have to be. Some members can abstain or vote present, but if everyone shows up he’s going to need something close to that. The problem is that the Republican majority isn’t going to be much more than 218.

But as of now, McCarthy has nothing like 218 votes in his pocket. He won the leadership race 188-31. A lot—but by no means all—of those 31 Republicans are performative jackasses. Prominent cacafuego Rep. Matt Gaetz, for example, has made it clear he won’t vote for McCarthy. Then again, McCarthy has lined up support from some of Congress’ most prolific bescumbers like Marjorie Taylor Greene, promising her committee assignments that a coked-up gibbon with a fetish for leg-humping would be better suited for.

McCarthy is in a nearly impossible situation. Consider Rep. Thomas Massie, whose theory of politics is that voters just want “the craziest son of a bitch in the race.” He told Politico last week that he’s stoked by the slim majority. “I would love for the Massie caucus to be relevant. If there’s a one seat majority, my caucus has one person. It’s me. So I can decide whether a bill passes or not,” Massie said, noting that 218 seats means that Republicans have subpoena power. “I’d be the wrong guy if you’re trying to find somebody who’s heartbroken that we don’t have a 40-seat majority.”

Imagine trying to run both the House and GOP caucus with that guy making demands all the time. Maybe he’ll want the official GOP Christmas card to feature the entire caucus wielding AR-15s before he agrees to raise the debt ceiling?

Now, we don’t know which 31 members voted against McCarthy, but save for Gaetz, it’s a safe bet that the majority of them were members of the House Freedom Caucus.

I have not been a fan of the House Freedom Caucus for quite a while. I used to be much more sympathetic when the members claimed to actually be champions of fiscal restraint and all that. But during the Trump years, they mostly threw away all of their ideological purity in favor of being Trump’s political shock troops.

In an interview for The Dispatch Podcast, Mick Mulvaney—a founding member of the HFC until he left for the Trump administration—offered Steve Hayes his explanation for what happened to them:

When I got over to the White House … the president’s like, “Tell me about these guys.” [The Freedom Caucus.] And I’m like, “These guys are gonna be your very best supporters.” And he’s like, “Why?” They’re very conservative and he knew he wasn’t that conservative. And I said, “Mr. President, they are your voters because at the core the Freedom Caucus is anti-establishment.” That’s what it is. It’s against Washington for the way Washington has been. It took the form of a conservative group, an ultra-conservative group on some things, but the spirit of it was anti-establishment, so they had kindred spirits with Donald Trump.

Now, I think this is an admirably honest explanation for an utterly asinine excuse. Being “anti-establishment” regardless of context or the nature of the establishment isn’t heroic, never mind conservative. It’s radicalism.

Mulvaney basically agrees. He continued:

What I think happened was that after Trump got elected and the Freedom Caucus sort of moved to front and center on Fox News, is that they realized that there’s a lot more energy behind being nutjobs than there is being reasonable. And the Freedom Caucus went hardcore and moved away from some of our founding principles.

In other words, all of that stuff about being incorruptible Catos turned out to be bulls—t when it was actually put to the test. And really, who can blame them? I mean, how can the fiscal solvency of the nation and the glories of God-given freedom compare to six minutes of political poo-flinging on Hannity?

Well, time is a river and it has delivered us to new shores. Now the House Freedom Caucus has demands for its support of McCarthy, and they are … pretty reasonable.

I’m not enough of a congressional procedure nerd to judge all of them, but I could get behind a lot of what they want. When I saw the headline on this piece by our intrepid Capitol Hill spelunker, Haley Byrd Wilt, I was worried that she had been tucking into Steve’s stockpile of Spanish wine.

“Really, the Freedom Caucus’ Reform Opportunity?” I thought. Does Jim Jordan want to allow voting from the House gym?

But then I read the demands, and a lot of them are affirmatively good. For instance, the caucus wants to “restore the independence of committees”:

Instead of being selected based on loyalty towards and fundraising for party leadership, committee chairs should be elected by the members of their committee based on their qualifications and effectiveness.

Furthermore, committees need the ability to defend their jurisdiction from being ignored. Republicans should prohibit legislation from coming to the floor unless each committee of jurisdiction has acted on it, unless waived by the Republicans in the relevant committees.

I’m down with that. It also wants members to be able to offer amendments and have buy-in on legislation. There’s other good stuff in there, too, like abolishing COVID-era voting by proxy. Enough of that already. There’s also stuff I disagree with. I don’t think all legislation should have majority support from the majority party. For prudential reasons I’m at least skeptical about the demand to make it easy to overthrow speakers. But as that would be part of returning the House to regular order, I can’t say it’s unreasonable either.

Anyway, my point is that, for whatever reason, the House Freedom Caucus is actually demanding stuff that would make the House function the way it’s supposed to function.

I’m a broken record on this point, but Congress is supposed to be where politics happens. Legislation is supposed to bubble up from below, not be handed down on stone tablets by leadership. Committees are supposed to be hotbeds of haggling, debate, expert testimony, etc. As Justin Amash put it last year:

Congress is supposed to be a place where you discover outcomes. It’s not supposed to be a place where a few people get in a room, craft legislation and then foist it on everyone else and say, hey, this is what you—this is what you’re going to take. Take it or leave it, and if you’re not with us, then you’re against us and we’re in, you know, we’re in gridlock.

Congress was intended to be a catch basin for political passion. But over the last two decades its intake pipes have been jammed. So instead the political passion spills out into broader society. If that metaphor doesn’t do it for you, think of Congress like that conference room in Apollo 13 where they dump all the doodads and whatchamacallits aboard the ship and tell the engineers something like, “You figure it out.”

I get why Paul Ryan wanted to restrain the hotheads’ ability to wreak mischief. But that strategy didn’t yield fewer hotheads, it yielded more hotairheads like Matt Gaetz who actually think the job of a congressman is to yap on TV. Better to give politicians the ability to make consequential mistakes so that voters have something to judge them by other than soundbites.

When Congress (and political parties) doesn’t sponge up all the bile of politics, it oozes out into everyday life—and TV studios—and makes everything worse.

Anyway, we don’t need to get into all of that again here. Let’s get back to my original point. I don’t know why the House Freedom Caucus is suddenly sounding reasonable and civic-minded. I don’t know what role cynical self-interest plays in some or all of it. I’m no longer capable of thinking the group—as a whole—is driven by purely noble motives. It’s entirely possible that its members want opportunities to be unfettered rabble-rousers. But what’s apparent to the naked eye is that they think this is in their political interest.

Whatever their motivations, the political climate is driving them to propose good things, and it’s making it possible that good things will actually happen.

The deliciously and deservedly painful thing for Kevin McCarthy is that he wanted all of the powers of the speakership that the speakership shouldn’t provide. His fever dreams of the gavel being a political Mjolnir may have to give way for him to get the dainty hammer at all, making all the pieces of his political soul he sold to get here seem wildly overpriced. And if that seems unfair, so be it. As Moses told the unworthy Israelites with unreasonable expectations, “That sucks for you.”

McCarthy’s misery is that the only way for him to survive the stormy weather is to hide underneath the Freedom Caucus’ gaberdine. Because misery, like politics, makes for strange bedfellows.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.