Dear Reader (Including the 7,199 people who are supposedly more influential than me),

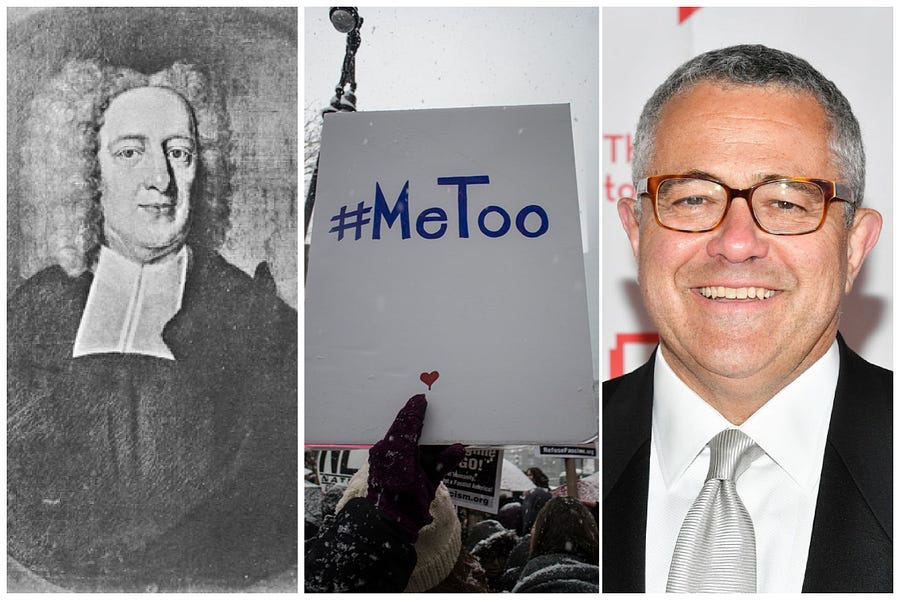

Trigger warning: This “news”letter will mention Jeffrey Toobin.

Editor’s Note: Unlike the last “news”letter about Mr. Toobin—which caused a few people to cancel their subscriptions—the jocularity will be kept within the borders of propriety and relevance.

Author’s Note: I reserve the right at any time I deem necessary—or fun—to stray across those borders with the impunity of the Viet Cong on the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Musical Note: ♬

Okay, enough of that.

The New York Times has a big, mostly predictable story on the fall of Jeffrey Toobin. The first thing of note (or the fourth if you count the above) is the headline:

The Undoing of Jeffrey Toobin

How a leading man of legal journalism lost his sweetest gig.

The piece sets this up as some kind of mystery, even though just about everyone who has heard of this story knows how he lost the gig. (Again, I don’t want to offend anybody, so I’ll avoid clinical descriptions. During an online Zoom meeting, he let his mouse out of the house and proceeded to give it a hand.)

In other words, the big reveal of this journalistic whodunnit was his big reveal to his colleagues. (I mean “big reveal” in the literary, and not necessarily the anatomical sense.) The resolution of “How a leading man of legal journalism lost his sweetest gig” was known to the reader from the outset.

Let me explain this in a weird way: Sometimes certain things are explanations in and of themselves, without need of further commentary. For instance, one of my best friends in college was known around campus as one of the nicest people you’d ever meet. One day, a mutual friend who went to high school with him, said “Yeah, Andy’s a very decent guy, but you know his brother’s even nicer.”

I said, “Come on. How could anyone be nicer than Andy?” The guy paused for a second and then said, “His brother was a hugger at the Special Olympics.” He literally waited at the finish line and hugged every kid after they finished.

“Oh. Got it.” I replied.

Or here’s another story. On a business trip in India, my Dad had dinner with a major mogul in Bollywood. The multimillionaire said to my Dad, “Sid, I love your country. America is wonderful. But you can’t really be rich there.”

My Dad said something like, “What are you talking about? We have the richest people in the world in America.”

The mogul paused for a moment, and then said, “Let me put it this way: I have never tied my own shoes.”

“Ah, I see,” my Dad replied.

Now, imagine I was out of the loop and asked someone why Jeffrey Toobin lost his gig at The New Yorker and the answer was, “He pleasured himself on a Zoom call in front of his colleagues and boss.” I might have a lot of questions, but “Why was he fired?” really wouldn’t be one.

Apparently, that just shows I’m ensconced in a bourgeois, Judeo-Christian mindset.

From the New York Times:

Malcolm Gladwell, one of the magazine’s best known contributors, said in an interview: “I read the Condé Nast news release, and I was puzzled because I couldn’t find any intellectual justification for what they were doing. They just assumed he had done something terrible, but never told us what the terrible thing was. And my only feeling — the only way I could explain it — was that Condé Nast had taken an unexpected turn toward traditional Catholic teaching.” (Mr. Gladwell then took out his Bible and read to a reporter an allegory from Genesis 38 in which God strikes down a man for succumbing to the sin of self-gratification.)

Even Mx. Gessen, who initially found the incident “traumatic,” said they now feel sympathy for Mr. Toobin. “I think it’s tragic that a guy would get fired for really just doing something really stupid,” they said. “It is the Zoom equivalent of taking an inappropriately long lunch break, having sex during it and getting stumbled upon.”

Let’s take these in reverse order.

It’s really not like that at all. Put aside that at the outset of his faux pas he blew an “air kiss” to someone who may or may not have been his wife; I cannot help but notice that in Gessen’s analogy the only behavior described as “inappropriate” is the length of the lunch break. Even using Gessen’s hypothetical, it’s more like attending an office meeting and then, when everyone decides to break for lunch, getting jiggy at your desk on the assumption no one will come back to the office for a while.

“Hold on a second guys, I left my wallet on my desk, let me grab it. … OH GOD JEFFREY WHAT ARE YOU DOING?”

The point is that normal people take minimal precautions not to make these kinds of mistakes because we live in—what’s that word?—oh right, a society.

And then there’s Malcolm Gladwell. The philosophical concept of Occam’s Razor holds that the simplest explanation is the most likely one. Or, as doctors sometimes say about how to diagnose a patient, “If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.”

If you read a press release announcing that a 60-year-old man—with a checkered sexual history—was fired for going into manual override at a meeting and the “only way” you can explain it is that the publisher of Vogue, Vanity Fair, and Glamour has made a shocking right turn toward Rome, you’re not even hearing zebras—you’ve spotted a herd of unicorns.

Gladwell’s confusion.

Okay, like The New Yorker, I’m basically done with Toobin. But Gladwell’s response is more interesting to me, because it illustrates how confused and confusing morality talk is today.

I’m generally a fan of Gladwell’s. He’s an odd dude, with a kind of “visitor from Mars” sensibility that I appreciate. He sees interesting connections that many of us take for granted. I try to cultivate the same detachment because it’s very useful for understanding all sorts of things. But there are limits to the Stranger in a Strange Land approach to commentary because sometimes it leads you to see connections that aren’t there. For instance, a visitor from Mars would be forgiven for thinking human beings are slaves to our canines because they lead us around and we pick up their poop.

What is strange about Gladwell’s conclusion is that he’s the sort of guy who would normally argue that taboos about sexual behavior don’t spring up ex nihilo. The story in Genesis that Gladwell cites—which, for what it’s worth, was already on the scroll shelves long before the Catholic Church was founded—surely has analogs in other cultures. I don’t know this for sure, but I strongly suspect that Jeffrey Toobin would get fired from many of the leading magazines in most Muslim, Hindu, or Confucian societies for similar behavior. Has Conde Nast taken an unexpected turn toward Koranic social teaching?

More to the point, Gladwell seems incapable not only of finding fault with Toobin’s behavior, but incapable of assigning blame to his own side’s moral system. Conde Nast, which no doubt is decidedly on the MeToo side of all these debates, made a mistake in Gladwell’s eyes. Okay. But one doesn’t have to suddenly imagine that the owners of Teen Vogue have gone Opus Dei to explain why MeToo-ers might have a problem with men exposing themselves to colleagues. The scalps of Matt Lauer, Louis C.K., Mark Halperin, et al, weren’t collected by Catholic Torquemadas; they were collected by Gladwell’s friends, colleagues, and peers.

Old morality and new.

So let’s put on those Martian goggles.

The sociologist Donald Brown famously compiled a long list of what he called “human universals”—manifestations of culture that can be found in every society. One theory behind such universals is that they represent evolutionary practices that ensure genetic success. Hence taboos on, say, incest exist pretty much everywhere and everywhen. The theological justifications for these taboos are lagging, not leading indicators. (Indeed, Catholic social teaching would concede as much in many instances, in that it claims to be rooted in natural law.)

I will grant that Brown did not include a taboo against Zoom-call-onanism on his list, but you get the point.

What is interesting to me is that for the last few years, we’ve been living through a particularly intense period of taboo destruction and taboo creation around sex. For conservatives, it’s easy to see the destruction. But the creation should be obvious too.

Seen through my own visitor-from-Mars goggles, it seems to me that as traditional religious and moral strictures have receded, a new explicitly secular project to replace them has been underway for quite a while.

We don’t need to run through all the examples, because if you’ve been paying attention, it’s been an almost daily affair: guidelines for how to ask for consent—sometimes at every stage of foreplay, all manner of language policing, efforts to eliminate due process in campus adjudication of sexual offenses, mandatory “awareness” training etc. Some of it is absurd. Some of it is a defensible effort to come up with new manners now that the sources of the old manners—traditional morality, religion, etc.—have been declared illegitimate.

Again, looked at from a distance, it looks like a war between Puritanism 1.0 and Puritanism 2.0. Of course, neither is strictly speaking “Puritanism” of the sort we associate with Cotton Mather. But given the zeal to police or sanctimoniously cast judgement on the behaviors of others with supreme moral confidence, I’m struggling to come up with a better label.

Regardless, whatever the right term is, one thing is clear: Holders of both worldviews despise each other, often needlessly so. When it was revealed that Mike Pence won’t attend events where alcohol is served without his wife, and that he won’t have dinner alone with women other than his wife, he was subjected to relentless scorn. Now, those aren’t my policies, but shorn of religious or scriptural ornament, he’s working from many of the same assumptions of the secular left (though the secular left won’t use phrases like “fallenness” or “sinfulness”). What seems to offend his critics is not that he’s trying to set bright lines to avoid sexual misconduct, but that he’s doing it for the wrong reasons.

Each side has its doctrines and incantation. And sometimes the arguments draw on serious and substantive differences in worldview, with good points scored on both sides. And sometimes it’s just partisan, tribal, garbage. If Mike Pence were caught in his own Toobin Missile Crisis, you can be sure that the folks at The New Yorker wouldn’t be so broadmindedly conflicted.

It’s sort of like all of the outrage from people like Kayleigh McEnany over the fact that a Biden aide called Republican “f*ckers” (ironically, the aide said it in Glamour, a property of the suddenly ultramontane Catholic Conde Nast). This is someone who defends a boss who routinely says Democrats are evil, criminal, etc. Perhaps a better example is the double standard of progressive officials who issue sweeping diktats about how to behave in a pandemic and then violate those rules in their private life.

Say what you will about the era when saying “America is a Christian nation” was neither aspirational nor nostalgic, but descriptive—we at least had a more worked-out way to debate moral issues. All factions could broadly draw on the same tradition to make their arguments. Broadly speaking, we lived in a world of moral consensus but theological pluralism. When Utah wanted to enter the union, many Americans said, “No way! Polygamy is wrong.” Utah eventually said, “Okay, we’ll get rid of polygamy,” and Americans said, “Yeah, okay. Come on in.”

Now, because the combatants draw on different wellsprings of morality and meaning, they think moral consensus is meaningless so long as there is theological division.

These fights would be bad enough on the merits, but they’re made infinitely worse by the American obsession—now turbo charged by cable news and social media—with hypocrisy policing. Every day on Twitter, I see noisy partisans obsessed with pointing out the inconsistency of their enemies while being utterly forgiving of—or entirely silent about—the inconsistency of their allies.

Indeed, the worst part is that each tribe gives their own avatars dispensation to contradict their own doctrines. Feminists in the 1980s and 1990s worked tirelessly to establish new taboos on sexual misconduct. Then Bill Clinton violated many of those taboos, and they threw them all out the window. Over roughly the same period of time Christian conservatives had a similar project—partly fueled by opposition to Bill Clinton—centered on notions of good character. They threw all of that out the same window for Donald Trump. If the feminists really cared about harassment and abuses of power, they should have been angriest at Bill Clinton. If the right’s professional moralists really cared about character, they should have been the most appalled by Donald Trump. And, just to put a bow on it, if the publications that have worked most assiduously in the last few years—positively and negatively—to purge the workplace of inappropriate sexual conduct really believed what they’ve claimed to believe, they wouldn’t see Toobin’s firing as a conspiracy out of The Da Vinci Code, but as the logical consequence of the regime they set up themselves.

That’s what visitors from Mars would expect. But, alas, we don’t live on Mars. There are days when I’m not even sure we live on Earth.

Canine update: So I jinxed it last week when I said Pippa had turned the corner on rolling in filth. She did it again on Thursday. There’s just something so wonderful about contrasting the crisp, clean winter air with the stench of deer scat that Pippa cannot do without. She really does love winter though. She loves it almost as much as Zoë, who had her first case of snow zoomies on Thursday morning. The problem with this weather is that the girls remain energized even after walks. Ralph, meanwhile, is very mad about the change in weather, and he’s not afraid to let us know. Ralph is a nocturnal creature, and he has appointments all evening around the neighborhood. Snow, ice, and freezing rain are inconvenient to his social calendar. The problem is he thinks we are in control of such things.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.