Hey,

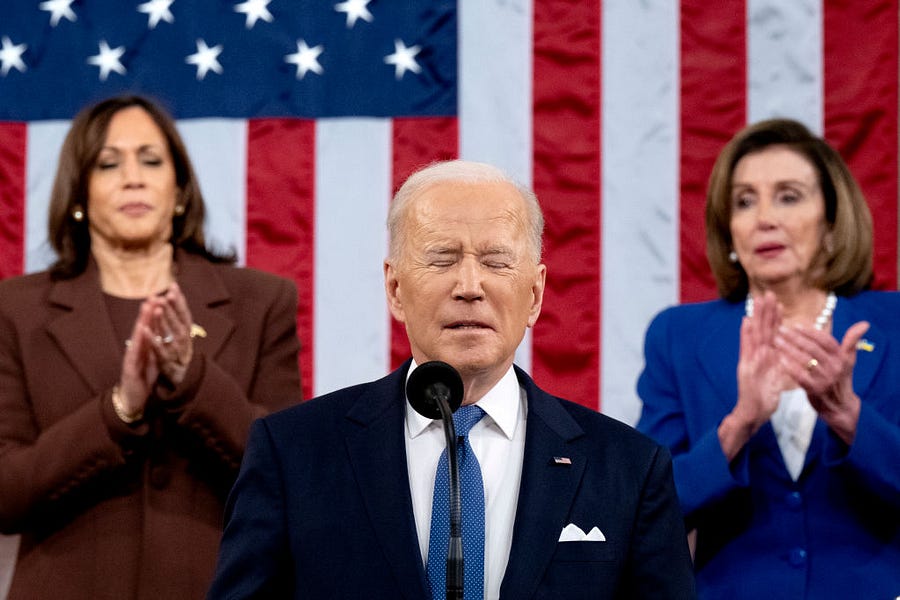

While I don’t technically belong to the Pundits Union, I still feel somewhat beholden to the contract. And the day after the State of the Union Address, if we’re obliged to write, we’re supposed to write about it. Fortunately, today’s Morning Dispatch does a really terrific job of covering the speech in a way that frees me up a bit.

On the other hand, I still feel obliged to chime in.

One problem is that the speech is already vanishing from my memory like a Polaroid picture in reverse.

In fairness, this happens to most such addresses. They’re all billed as huge events, then by the time Sunday shows roll around Chuck Todd or George Stephanopolous says, “It’s hard to believe that it was only this week that the president delivered his State of the Union Address. But I suppose we’d be remiss not to talk about it.”

But Biden is particularly ill-suited—or maybe perfectly suited—for what we’ve come to expect from the State of the Union. He’s like some W.W. Jacobs character who asks the monkey’s paw to make him a memorable speaker. The paw grants the wish, but what people tend to remember are his malapropisms and logorrhea. Ask me about most Biden speeches or my bus trip to Port Arthur, Texas, and the answer is pretty much the same, “Not much happened except for some weird stuff and it took forever.”

So yeah, I can do the rank punditry thing and ding Biden for this or that. He said we rank 13th in the world for infrastructure. Well, ackshully, that’s a dumb talking point. We’re No. 1 among the 10 largest countries in the world—whether we’re talking population or geographic size. He called Ukrainians “Iranians” because he does that kind of stuff all the time. And I’m fine with ribbing him for it provided you’re not someone who refused to acknowledge all the brown and wilted lettuce leaves and hairs-of-mysterious origin in Donald Trump’s daily menu of word salads.

I have plenty of more substantive criticisms, but I’ll just focus on two. The first, as spelled out in the Morning Dispatch (and by Ramesh Ponnuru and Matt Continetti), is that except for the first 10 minutes or so about Ukraine, this was a speech he could have—and maybe should have—given if his presidency was going great. With the important and laudatory exception of his broadside against defunding the police, Biden sounded like he doesn’t need to fix anything about his presidency or the plight of the Democrats more broadly. And that’s nuts.

According to the polls, Biden is slightly less popular than Donald Trump was at the same time in his presidency. The GOP went on to lose 41 seats in the subsequent midterms (and Trump went on to lose his reelection bid, Mike Lindell’s Giza cotton spreadsheets notwithstanding). He refused to even mention the most significant decision of his presidency—the abandonment of Afghanistan. And while he didn’t say the words “Build Back Better,” he kept talking it up like it was going to pass. Like his whole presidency, his State of the Union had this otherworldly quality to it. And in that fictional otherworld, Biden is a popular president with majorities in Congress that enable him to swing for the fences on New Deal scale programs.

Second, I didn’t like the way he talked about Ukraine. Sure, he paid some moving tributes to Ukrainian courage. But man, how hard is that? There was a certain parasitic quality to the rhetoric, in which America leeches off the glory and bravery of people standing up to potential annihilation. I’m glad we’re doing what we can for the Ukrainians and I’d like to do more, short of joining a shooting war ourselves if possible. But neither America nor the Biden administration are heroes in this unfolding story. We’re merely recognizing who the heroes are while we cheer and help from the sidelines.

More to the point, the disconnect between the gravity of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the tectonic changes it has elicited made the laundry list portion of the speech seem rather pathetic, solipsistic, and even more otherworldly than it would have been if there was no war.

But again, by the time you read this—if you read it all—you’ll probably be sick of hearing about the State of the Union already. So I’m going to switch gears and answer a question I invited last night. I tweeted:

A few folks asked, so what is the incentive?

Let me take a stab.

I’ll start by saying I don’t like the State of the Union Address as an institution.

We can all understand why presidents like it. Not only does the SOTU provide an opportunity to make the executive seem like the most powerful branch of government—which it is, but it isn’t supposed to be—it also results in a massive TV audience and a profusion of media coverage. It puts the president at the center of political life, elevating him as some sort of tribune of the people, speaking for all of them.

I can see how the formal rituals—the sergeant at arms shouting, “Madam speaker, the president of the United States”; the human props in the gallery; the sometimes hernia-inducing effort to proclaim, “the state of the union is strong”—have their charms. Maybe not so much for a curmudgeon like me, but I can see why other people—particularly journalists who cover such things — dig them.

But that’s one of the things I don’t like. It’s way too monarchical, promoting the presidency above Congress, at least symbolically. Remember, the State of the Union was intended to be a mandatory performance update from essentially an underling. In our constitutional system, Congress is the boss—because here the people rule—and the president is like Congress’ general contractor. He hires the roofers and plumbers and landscapers and, “from time to time” as the Constitution says, reports to his employer (or in this case his employers’ representatives) on how it’s going.

Yeah, I know, the analogy isn’t perfect, but it’s closer to the Founders’ intent than the quasi-idolatrous spectacle the State of the Union has become. The State of the Union should be more like an opportunity for Peter Gi bbons to turn in his TPS reports to a roomful of Lumberghs.

And this general contractor thing is the first incentive for the laundry list. Like pretty much every general contractor I’ve ever known, the president always comes and asks for more money. All politicians want to spend other peoples’ money, but presidents have to get it from Congress. The Constitution says the president is supposed to provide the State of the Union to “recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” Like a contractor looking to pad the bill with better faucets and more expensive bathroom tile, presidents (particularly Democratic ones) have a bottomless wish list of spending priorities. But unlike general contractors, they earn credit with the people they care about by asking for stuff they’ll never get.

Before I go deeper, let me pull up and say the most obvious reason this format has taken root is plain old habit. Experienced speechwriters and political consultants, protecting their own experience, tell the next generation, “This is the way we’ve always done it.”

But again, a long tradition of existence can only go so far in explaining something. Various interests and incentives have accumulated around the practice. Running through a long list of “priorities” is a key way to placate different constituencies in both the party and the vast bureaucracy that the president only nominally runs. Buying televised nods from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has intrinsic political value, and purchasing them with rhetorical non-sequiturs about dead policy initiatives is cheap.

Indeed, media coverage of such moments is itself a major driver because the consultant types know that individual soundbites will spread far and wide (“Here’s what the president said about new goat rodeo regulations”).This dynamic has only gotten worse with the rise of social media. Activists and party functionaries take the bits various constituencies want to hear but nobody else does, and send YouTube or Instagram clips to micro-targeted audiences. Thus, the biggest suckers are the people who actually watch it in the expectation of watching a coherent speech.

It’s sort of like the old joke about how the one book you should take with you to a desert island is the dictionary because it contains all the words of the other books in it.

Not to go all Mancur Olson on you, but the State of the Union is a bit like sugar subsidies, ethanol, or the Jones Act. We get stuff like that because of the phenomenon Olson memorably described as concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. Small groups benefit hugely from bad policies and are willing to exert great effort, and devote significant resources, to protecting them. If you’re a sugar mogul, you know that in America, first you get the sugar, then you get the power, then you get the women. But that’s not important right now. If you’re a sugar mogul, you make scads of money from subsidies that let you produce the sweet, sweet stuff protected from foreign competition. You’re willing to spend some of your sugar daddy bucks on keeping those policies in place. Meanwhile, voters and (non-Florida) politicians may want to get rid of the subsidies, but who’s going to go to the mattresses to get rid of them? Single-issue sugar-subsidy-repeal voters are hard to come by.

If you’re the literary sherpa guiding the drafting process of the State of the Union, you spend your days taking phone calls from activists and elected officials reminding you that this, that, or the other thing has to be mentioned. The dilemma is that the more things you mention, the more politically insulting the exclusions become.

Think of it this way. William F. Buckley didn’t like acknowledging all of the important people in a room when he gave a talk. It wasn’t because he wasn’t polite. He was possibly the most polite person I’ve ever known. The problem, he explained, is that once you start saying something like, “It’s great to see governor so-and-so and judge what’s-his-name,” the ruder you are going to be to the people you don’t mention. But because he was Bill Buckley, he illustrated the point by dropping some Latin. “Expressio unius est exclusio alterius”—to include one thing excludes another. I’m sure someone in the White House got a call this morning from some irate stakeholder who is outraged that Biden mentioned subsidies for daycare workers but didn’t say a word about the COVID-Positive Hamster Protection Act.

So this is why—with very few and very limited exceptions—SOTU addresses all begin and end with attempts at high-flown rhetoric but are crammed in the middle with tedious laundry lists of legislative asks and executive branch initiatives. They’re like a vegan Dagwood sandwich held together by two slices of dietetic Cicero bread, a classic example of something everyone hates but no one in charge has the courage or imagination to change.

And that’s the tragedy of Biden’s speech last night. I’ve given up waiting for Sister Souljah moments from this guy. He cares too much about winning the approval of his left flank in the name of non-existent party unity, even though two left-wingers cared so little about party unity that they actually gave formal responses to the Democratic president’s address.

But Biden could have done something different. He could have thrown away the calcified rhetorical rituals of the State of the Union and signaled to Americans and Ukrainians alike that this moment called for something different, something better. He could have talked plainly about how the international order is under threat and that America will lead. He could have prepared Americans for the inevitable costs—and there will be many—of what we’re doing and what Putin hath wrought. He could have taken a Trumanesque or Reaganesque stance, and then he could have stopped talking. But that’s too much to ask of most presidents—particularly this one.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.