Happy Monday! If you have the coronavirus or were exposed to the coronavirus, please don’t plow ahead with your Ozaukee County Oktoberfest fundraiser, or head back to the office to tell your staff in person, or order your assigned Secret Service agents to accompany you on a little joy ride. Just go and stay home.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

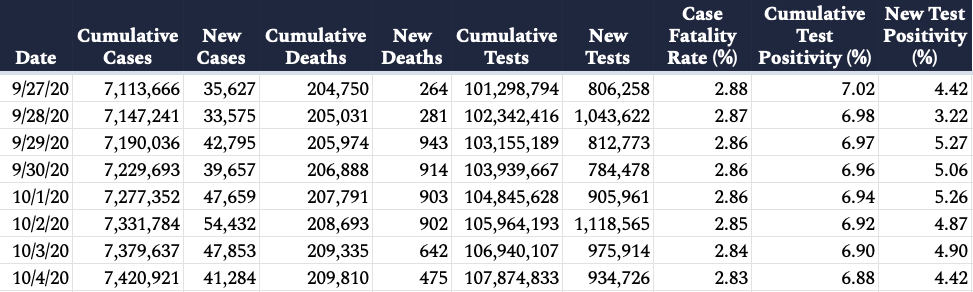

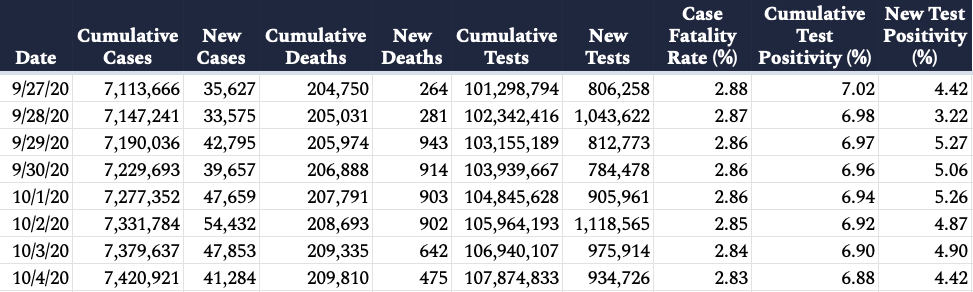

The United States confirmed 41,284 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 4.4 percent of the 934,726 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 475 deaths were attributed to the virus on Sunday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 209,810.

-

President Trump was hospitalized at Walter Reed Medical Center on Friday, hours after he announced he had tested positive for COVID-19. His doctors said on Sunday he may be discharged as early as today, but noted he is being treated with several experimental drugs and therapeutics.

-

A host of other prominent White House and Republican officials have tested positive for COVID-19 since President Trump announced he had contracted the virus: RNC Chairwoman Ronna McDaniel, Trump campaign manager Bill Stepien, former White House adviser Kellyanne Conway, Trump body man Nicholas Luna, former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, Sen. Ron Johnson, Sen. Thom Tillis, and Sen. Mike Lee.

-

Employers added 661,000 jobs in September, according to a Friday Bureau of Labor Statistics report. The unemployment rate fell 0.5 percentage points to 7.9 percent, but the rate of the economic recovery is slowing. There are currently 10.7 million fewer jobs in the United States than there were in February.

-

Despite several senators quarantining because of exposure to the coronavirus, the Senate will proceed with Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation hearings as scheduled, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said Saturday. McConnell did, however, delay the Senate’s return from recess until October 19, meaning portions of Barrett’s confirmation hearings will likely be virtual.

-

Senior aides of Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a whistleblower complaint on Thursday accusing the state’s top lawyer of bribery, abuse of office, improper influence, and other potential federal crimes.

-

Cal Cunningham, the Democratic Senate candidate in North Carolina, admitted on Friday to sending flirtatious text messages to a woman who is not his wife. “I have hurt my family, disappointed my friends, and am deeply sorry,” Cunningham said, making clear he was not leaving the race.

-

St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson died on Friday at age 84 of pancreatic cancer.

The President vs. the Pandemic

When our last newsletter hit your inboxes, Washington had just been upended by President Trump’s overnight diagnosis with COVID-19. Since then, reams of additional reporting and information have come out. But as with so many stories with this White House, much of what we have been told is a garbled, contradictory mess—the truth feels little clearer than it did in those first frantic moments after Trump’s announcement.

Let’s start with what’s plain and clear. After experiencing symptoms of the coronavirus, including a cough, fever, and concerning oxygen levels, President Trump traveled to Walter Reed, the Bethesda, Maryland, military hospital where presidents are traditionally treated, on Friday afternoon. He has since received several forms of therapeutic treatment, including an antibody cocktail of Regeneron, the antiviral Remdesivir, the anti-inflammatory dexamethasone, and sporadic supplemental oxygen. He has also released several upbeat videos thanking Americans for keeping him in their prayers, and taken one impromptu motorcade ride to wave at supporters outside the hospital.

Beyond that, things get murkier. Statements from the White House and the president’s doctors have often been contradictory and misleading in answering crucial questions about the president’s health. Let’s take a minute to sort through the timeline since COVID crashed the White House, and what the administration has had to say about it.

On Wednesday, President Trump held one of his trademark rallies in Duluth, Minnesota—the fourth such rally over the previous week. He spoke for roughly 45 minutes, much shorter than his typical rally speeches. On the return journey from Minnesota aboard Air Force One, Hope Hicks began to feel sick and was quarantined from the rest of the campaign staff. It was later reported that Hicks had tested negative for COVID-19 that morning.

On Thursday, things started moving quickly. Hicks took another COVID test and learned she had the coronavirus. White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows later said that the president was informed of Hicks’ positive test early that afternoon, just as he was preparing to hold a fundraiser with wealthy GOP donors in Bedminster, New Jersey. Trump elected to go on with the fundraiser anyway, a move that would reportedly later cause panic among the unwitting attendees.

After the fundraiser, it appears Trump went through the regular White House testing protocol: At some point, he took a rapid COVID antigen test, and when that came back positive, took a second, more sensitive PCR test. (It’s unclear when the president’s last negative test took place, as White House officials and his doctors have refused to provide that information.) As the news of Hicks’ diagnosis started to leak out, and while he was still waiting on his second test result, Trump called into Sean Hannity’s Fox News show to discuss the illness. He did not disclose his preliminary test result. Once his second test did come back positive, Trump announced that he and his wife Melania had contracted the virus in a late-night tweet. Minutes later, the president’s physician Sean Conley released a statement saying that the president and first lady were well and planned to undergo treatment at home at the White House.

By Friday morning, Trump was displaying significant symptoms. He had a fever and difficulty breathing, and the oxygen content of his blood was dropping—a sign that his lungs were struggling to do their jobs under the weight of the infection and corresponding inflammation. He first received supplemental oxygen from White House doctors at this time.

We didn’t find that out until significantly later, however. In real time, the White House was assuring the public there was little to worry about. “This is going to be very mild or asymptomatic for the overwhelming majority of people,” radiologist and presidential COVID adviser Scott Atlas told Fox News Friday morning. Mark Meadows told reporters that Trump had “mild symptoms.”

By that afternoon, with the president’s condition worrying his advisers and medical professionals, a decision had been reached: Trump would go to Walter Reed. Doctors there put him on a course of remdesivir, an antiviral thought to be most useful when administered in the early going of a COVID case. Earlier in the day, he had also been treated with an antibody cocktail from biotech company Regeneron that has shown promise in shortening a bout of COVID in preliminary clinical trials. The Regeneron cocktail is not yet approved by the Federal Drug Administration, and the president was provided it under a “compassionate use” exception. Dr. Conley also disclosed Trump was taking vitamin D, melatonin, zinc, and a daily aspirin—presumably to guard against COVID’s tendency to clot the blood.

At this point, the White House had yet to acknowledge that the president had experienced anything particularly alarming and continued to provide upbeat assessments of the president’s condition. The remdesivir, the Walter Reed trip, and the Regeneron cocktail were all characterized as steps taken “out of an abundance of caution.”

By Saturday morning, Trump’s fever had receded, but he was again struggling to get the oxygen he needed. He received another bout of supplemental oxygen. Following this, his doctors decided to put him on another medication to help calm his lungs: the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone.

This was a significant step. Unlike remdesivir, dexamethasone doesn’t go after the virus itself, but rather soothes the haywire immune response that frequently occurs during a serious COVID infection. This fact, coupled with some nasty side effects (including, in some cases, depression and mania) is why experts recommend the treatment only for severe cases.

The White House did not disclose that Trump had gone on dexamethasone, however. Instead, at a noon press conference, Dr. Conley was all smiles: “The team and I are extremely happy with the progress the president has made.”

But this conference proved a turning point in two ways. First, Conley’s awkward responses to media questions revealed for the first time, seemingly by accident, that Trump had needed to take supplemental oxygen. Asked point-blank whether Trump had taken it, Conley could only stumble through some highly dubious answers about how Trump was not on oxygen at that particular moment.

Then, following the press conference, White House chief of staff Mark Meadows pulled aside reporters in the White House pool with a very different message than the cheery one Conley had pushed. Trump’s vitals over the previous day had been “very concerning,” Meadows said, and “we are still not on a clear path to a full recovery.” Meadows initially provided that information on a “not for attribution” basis, meaning reporters could use it but couldn’t explain precisely who had provided it, beyond a generic reference to “a source familiar with the president’s health.” The entire assessment read: “The president’s vitals over the past 24 hours were very concerning and the next 48 hours will be critical in terms of his care. We’re still not on a clear path to a full recovery.”

But given directly contradictory nature of the information provided by the president’s top doctor and the president’s top aide, reporters immediately pushed to attribute the subsequent information to Meadows. A video of Meadows gathering reporters and requesting to talk to them off the record made its way onto social media. The Associated Press and The New York Times then attributed the information to Meadows.

Shortly after being outed as the source of the worrisome assessment, Meadows gave a much sunnier report to Reuters, one that aligned with the official—but misleading—report provided by the medical team. “The president is doing very well. He is up and about and asking for documents to review. The doctors are very pleased with his vital signs. I have met with him on multiple occasions today on a variety of issues.”

Meadows tried to square the circle on Saturday evening in an appearance on “Justice with Judge Jeanine,” on Fox News.

Trump himself surfaced again Saturday afternoon with a four-minute video in which he thanked his supporters for keeping him in their thoughts and discussed his treatment. He was upbeat and seemed cheerful. The White House also released photos of Trump that purportedly showed him busy attending to his presidential duties, including signing several presidential proclamations.

On Sunday, Trump seemingly had improved somewhat: He had not had another episode of falling oxygen levels, at any rate, and his fever had not returned. But at his daily press conference, Dr. Conley didn’t get to field many questions about that, as he was forced to contend instead with the misleadingly cheerful picture of Trump’s health he’d given out the day before.

“I was trying to reflect the upbeat attitude that the team, the president, over the course of illness, has had,” he said. “When you’re treating a patient,” another official suggested later, “you want to project confidence, you want to lift their spirits, and that was the intent.”

Yet while claiming to come clean about his misleading statements the day before, Conley made still more hedging statements on Sunday that prompted further speculation about Trump’s condition. Asked what scans of Trump’s lungs had revealed about the progress of the illness, Conley was vague, but didn’t say they were undamaged: “There’s some expected findings, but nothing of any major clinical concern.” He also acknowledged that Trump’s oxygen had fallen the previous morning—despite having denied exactly that the day before. He declined to answer whether Trump’s oxygen levels had dropped below 90 percent, only insisting they hadn’t gotten into “the low 80s.” (A normal reading is between 95 and 100 percent.) And he belatedly admitted that Trump had been put on a program of dexamethasone—but only during questioning.

For his part, President Trump released another short video Sunday showing him seemingly in good spirits. He followed that up with a short, spontaneous trip outside the hospital, bidding the Secret Service to drive him around the block to wave at supporters who had gathered there.

What’s the Takeaway?

This weekend found the Trump administration repeatedly deceiving and obfuscating about the president’s condition during a time when the nation was counting on them for information about their commander-in-chief—but that in itself is, unfortunately, not particularly surprising. It does, however, make it a bit more difficult to answer the key question before us: How much danger is President Trump still in?

It’s encouraging to see that President Trump is feeling well enough to be up and about. But that doesn’t tell us the whole story. One notable characteristic of this vile disease has long been that the pneumonia it causes often doesn’t feel as oppressive as many other pneumonias. The dramatic spike in home deaths in the early days of the pandemic was due in large part to the phenomenon of patients convalescing at home who felt fine as their oxygen levels crept stealthily down before cratering all at once. Here’s how one doctor described it to us all the way back in April:

Unlike a lot of other illnesses that affect the lungs, patients seem to be relatively comfortable at home, but at the same time if you check the oxygenation of their blood, it’s rather low compared with most other pneumonias. But they seem to compensate well for it until they get down to like 93 or 91 percent, and then they just plummet. And at that point, if they’re not in the hospital and they don’t have access to oxygen and other therapeutics, they basically die within a matter of hours. … A lot of elderly people are living alone, and they’re getting by, and they’re on the phone with their family saying, ‘I’m sick, but I’m okay, don’t worry about me.’ And then they’re dead.”

Conley’s own evasive statements—recall he declined to say whether Trump had ever dipped below 90 percent oxygen saturation—suggest the president has himself flirted with this danger over the past few days, although fortunately while under the strict supervision of the best doctors in the world and with access to the oxygen and therapeutics that have proven helpful.

Maybe the best possible thing to say about Trump’s condition, then, is that it’s both still serious and a testament to how far we’ve come in treating this virus over the course of this harrowing year.

Trump’s doctors have suggested he might be discharged from Walter Reed later today, a prospect some have found concerning. It’s worth noting, however, that “going home” would simply mean Trump would be traveling from one state-of-the-art medical facility to a place where he can still access the best treatment available. And it’s also possible, as one COVID doctor noted to us yesterday, that such suggestions are just more cheerful talk intended to keep Trump’s spirits up. Don’t be too alarmed, in other words, if he is discharged—and don’t be too alarmed if he’s not.

Worth Your Time

-

With Uber finding itself embroiled in a possibly existential battle in California, The Wall Street Journal’s Allysia Finley sat down with the ride-sharing company’s CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi. Assembly Bill 5 would force Uber and other rideshare apps to classify drivers as employees rather than contractors, entitling them to “fixed schedules, including meal breaks, and state-mandated benefits regardless of how many hours they work.” Khosrowshahi contends that, “If you’re of the opinion that Uber is an employee with this new model, then you’d be of the opinion that Airbnb is employing their hosts as well and eBay is employing their sellers.” Check out the piece to get insight into the company’s strategy for self-driving cars and changing American attitudes towards car ownership.

-

We hear the term all the time, but what exactly is a “superspreader event?” Katherine Harmon Courage tries to answer that question in her latest piece for Vox. The coronavirus’ airborne nature and aerosolization render it tragically suited for mass transmission events. “An infected person could seed a poorly ventilated indoor space with virus without even getting physically close to all the people they end up infecting,” Courage notes. But very few of these superspreader events occur outdoors. “A team of researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has been collecting data on these superspreading events in a public database,” she writes. “Only one of the 22 cluster location types the team analyzed in a preliminary study was an outdoor setting.”

Presented Without Comment

Also Presented Without Comment

Also Also Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

“For Christians, there should be no such thing as schadenfreude and no thought of karma,” David writes in his Sunday French Press. In discussing how and why Christians of all political stripes should be hoping for President Trump’s recovery from COVID-19, David argues “we shouldn’t simply pray that a president’s trials cease. We can and should also pray that his trials bear fruit—the fruit of humility and repentance.”

-

In Friday’s late Late-Week Mop-Up, Sarah was joined by election lawyer Chris Gober for a conversation about how Trump’s coronavirus diagnosis affects the election and how campaigns handle Election Day legal challenges. “My expectation is that, assuming the presidential race is very close, and especially the down-ballot races, we’re not going to know the results of the election on election night,” Gober said. “My expectation is that we are going to have so many mail-in ballots that still need to be counted, that that is just going to take time to finish that process … the outcome of these elections really could be hanging in the balance while we continue to do that counting.”

-

Jonah’s Friday G-File went after our “troll addiction epidemic,” the compulsive need of partisans to define their political opposition by its worst members. It’s a feedback loop that incentivizes destructive behavior. “Just as there are a lot of liberals and Trump critics who want to be vile jackasses about Trump’s [COVID-19] predicament,” he writes, “there are lots of conservatives and Trump supporters who want them to behave that way. Each side has an incentive structure to pick the worst examples of the other side and say, ‘See, this is what they’re all like!’”

-

On the latest episode of the Dispatch Podcast, Sarah and Steve spoke with Dr. Jonathan Reiner—Dick Cheney’s former physician and a consultant to the White House Medical Unit during the Bush, Obama, and Trump years—about the White House’s negligence leading up to Trump’s COVID-19 diagnosis, and what the president’s doctors should be doing now. Audrey wrote a piece for the site featuring analysis from the interview.

Let Us Know

Have you contracted COVID? If so, was your experience with the illness easier or more difficult than you expected? If not, what would you consider to be the riskiest thing you’ve done these past seven months in terms of exposure to the virus?

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), James P. Sutton (@jamespsuttonsf), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Photograph by Alex Edelman / Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.