Happy Thursday! Until Congress changed the date in 1933, presidential inaugurations were held on March 4. Not unrelated: American intelligence and law enforcement officials are warning of another QAnon-inspired plot by a militia to storm the U.S. Capitol today.

Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

-

Maj. Gen. William Walker, commanding general of the D.C. National Guard, testified before the Senate Homeland Security and Rules committees Wednesday that his response to the January 6 Capitol insurrection was delayed three hours due to “unusual” restrictions by senior leadership that inhibited guardsmen from entering the fray.

-

The U.S. Al Asad air base in Iraq came under rocket fire of unknown origin Wednesday, resulting in a heart attack and subsequent death of an American civilian contractor. The attack comes less than a week after the U.S. strike on Iran-backed militia groups in Syria. Whether the attack is directly attributable to Tehran or one of its regional proxy groups, it likely signals an escalation in tensions between the U.S. and Iran.

-

In an effort to boost support for his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill in the Senate, President Joe Biden on Wednesday approved a plan proposed by centrist House Democrats to lower the income eligibility for the bill’s $1,400 stimulus checks. Should the bill pass, only those who earn $80,000 or less would be eligible for direct payments, an income cap that is $20,000 less than the last round of stimulus checks that were sent from the federal government under the Trump administration.

-

The House passed the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act (JIPA) on Wednesday almost entirely along party lines. The Democrats’ police reform measure was first introduced and passed last summer, but it now has a slightly better chance of becoming law. Democrats will, however, need 10 Republican votes in the Senate to advance the bill to President Biden’s desk.

-

H.R. 1, a bill that provides for sweeping election reform, including same-day voter registration, early voting, drop-off boxes, and provisions regulating campaign finance, passed the House on Wednesday.

-

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo apologized Wednesday for acting “in a way that made people feel uncomfortable,” but said he has no plans to resign despite three women levying allegations of sexual harassment against him.

-

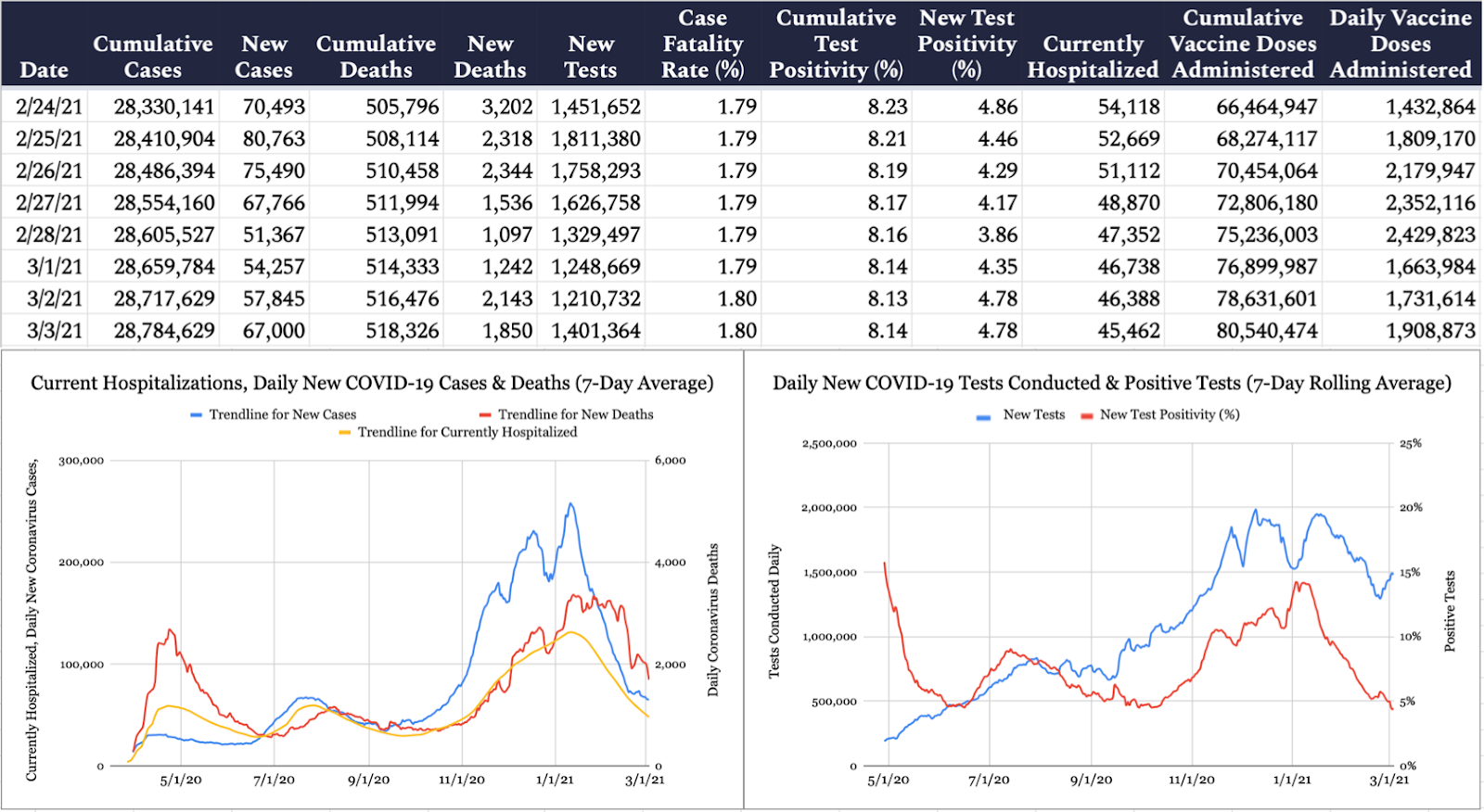

The United States confirmed 67,000 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday per the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, with 4.8 percent of the 1,401,364 tests reported coming back positive. An additional 1,850 deaths were attributed to the virus on Wednesday, bringing the pandemic’s American death toll to 518,326. According to the COVID Tracking Project, 45,462 Americans are currently hospitalized with COVID-19. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 1,908,873 COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered yesterday, bringing the nationwide total to 80,540,474.

Why Did It Take So Long to Deploy the National Guard?

The commanding general of the Washington, D.C., National Guard told senators Wednesday that it took longer than three hours for former President Donald Trump’s Defense Department to allow the National Guard to deploy to the Capitol building on January 6. The delay was caused by officials debating the optics of the action and unexplained communication problems, he said.

Maj. Gen. William Walker said he received “a frantic call” from then-Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund at 1:49 p.m. asking for help. “Chief Sund, his voice cracking with emotion, indicated that there was a dire emergency on Capitol Hill and requested the immediate assistance of as many guardsmen as I could muster,” Walker testified.

Walker said he immediately told senior Army leaders about the request. But he didn’t receive word that the troops could depart for the Capitol until 5:08 p.m.—three hours and 19 minutes later.

“It shouldn’t take three hours to either say yes or no to an urgent request,” Walker told senators. “In an event like that, where everybody saw it, it should not take three hours.”

Senior Pentagon official Robert Salesses also testified before the Senate Rules and Homeland Security committees Wednesday. He said the acting defense secretary approved full activation of the D.C. National Guard at 3:04 p.m., but final approval to send them to the Capitol building did not come until 4:32 p.m., leaving a more than half-hour gap between approval and Walker learning at 5:08 p.m. that he had the green light to deploy the troops.

Pressed by Sen. Roy Blunt to explain the delay in informing Walker of the approval, Salesses did not offer details but acknowledged it is “an issue.”

Notably, none of the Pentagon officials who actually made decisions on January 6 testified Wednesday. Blunt told reporters he wants to hear from former Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy and former acting Defense Secretary Christopher Miller.

During the hearing, Walker also raised concerns about his own inability to quickly redirect about 150 guardsmen who were already helping with traffic control that day. He said those troops were ready to step in hours earlier.

“I believe that number could have made a difference,” he said. “We could have helped extend the perimeter and helped push back the crowd.”

Not only was Walker severely restricted in how he could direct the troops who were handling traffic control, but he also had to seek explicit permission from then-Army Secretary McCarthy to deploy quick-reaction force service members.

Walker said that in other instances in which the D.C. National Guard has provided support to the metropolitan police and other law enforcement agencies—like planned rallies, marches, and protests—a standard component is the preparation of a quick-reaction force. He said the force entails a number of guardsmen held in reserve who are equipped with civil disturbance response equipment like helmets, shields, and batons. The force is “postured to quickly respond to an urgent and immediate need for assistance by civilian authorities,” Walker noted. On January 5, the day before the attack on the Capitol, McCarthy withheld the normal authority for Walker to employ the quick-reaction force.

Walker said he found it “unusual” that McCarthy included a requirement that he obtain permission before sending the troops to respond to the emergency. He added that he has not previously had such restrictions, including when the D.C. National Guard played a role in responding to demonstrations over the police killing of George Floyd last summer.

Wednesday’s hearing came after the same Senate panel heard from former Capitol security officials last week. Those officials largely blamed the intelligence community for their failure to protect the Capitol, claiming the details they received beforehand did not warrant a more significant response than they have had for previous large protests. But there was abundant open source information that could have raised red flags if it had been taken seriously: Some Trump supporters openly shared their plans to attack the building on pro-Trump forums before January 6, and intelligence indicated there was a potential for violence.

One warning, in particular, has received attention in the wake of the riot: An FBI field office reported January 5 that extremists were urging people to go to D.C. and that they were preparing for “war.” The U.S. Capitol Police intelligence unit received the warning, but it was not shared with top decision makers. Even if it had been sent up the chain of command, acting Capitol Police Chief Yogananda Pittman told lawmakers last week, it would not have changed the force’s security posture because it reflected intelligence they had already seen.

FBI Director Christopher Wray testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee for the first time since the attack earlier this week. He said the information in the field office warning was uncorroborated.

“The information was raw. It was unverified,” Wray said, adding that under better circumstances the FBI would have taken steps to determine whether it was reliable.

Wray also emphasized the danger of domestic terrorism, saying it “has been metastasizing across the country for a long time now, and it’s not going away any time soon.”

For now, the Capitol remains on high alert, surrounded by fences topped with razor wire and protected by National Guard troops. Pittman, the acting Capitol Police chief, said last week that the force is concerned about threats to attack the building when President Joe Biden delivers his first joint address before Congress. More immediately, there have been warnings about a potential attack today, March 4, because of a false conspiracy theory that maintains former President Donald Trump will be sworn into office for a second term on this date.

It isn’t the same scenario that prefaced the storming of the Capitol on January 6—there isn’t a large protest featuring Trump planned, and security around the complex is much stronger today than it was then. But a small group of domestic terrorists could do very real damage and could endanger the safety of members of Congress as they travel to and from the building. Security officials are taking the threat seriously.

The Capitol Police said in a statement yesterday that the agency has “obtained intelligence that shows a possible plot to breach the Capitol by an identified militia group on Thursday, March 4.”

“The United States Capitol Police Department is aware of and prepared for any potential threats towards members of Congress or towards the Capitol complex,” the statement added.

“We have already made significant security upgrades to include establishing a physical structure and increasing manpower to ensure the protection of Congress, the public, and our police officers.”

House leaders are also wary of the situation: They moved up votes last night that were previously scheduled for today so members could leave for the week early. The Senate, meanwhile, is gearing up for a protracted debate over President Biden’s nearly $2 trillion coronavirus aid bill. Democratic leaders aim to pass it in the coming days.

The Child Allowance Debate

As the Senate debates the specifics of President Biden’s nearly $2 trillion* stimulus package, the status of one key provision remains somewhat murky: the so-called “child allowance,” a direct federal monthly payment to parents of minor children. The bill under consideration would dole out payments amounting to $3,600 per year for young children and $3,000 per year for older ones for a single year under the auspices of emergency pandemic relief.

On Wednesday, however, Biden told House Democrats on a private call that he would support making that extension permanent, according to the Washington Post—an admission that raises some interesting and prickly legislative logistical questions.

To begin with, it’s important to explain why the proposal as it currently stands is designed to sunset in the first place. Senate Republicans have made clear they’re none too keen on the stimulus package as a whole, which they argue is poorly targeted and stuffed with progressive policy changes unrelated to the pandemic. As a result, Democrats are operating under the assumption they’ll need to pass the bill with little to no Republican support. Since they control only 50 votes (plus Vice President Harris’s tiebreaker), they are making use of the filibuster-proof process known as budget reconciliation.

We’ll save a fuller explanation of reconciliation for a later date (in fact, pencil it in for next week’s Uphill!), but, for our purposes, one element is crucial here: Only bills meeting certain criteria are eligible to be passed under reconciliation, and one of those criteria is that the bill must be deficit-neutral after 10 years. A bill that includes dollops of new federal spending or eats into federal revenues without making up those changes elsewhere must thus sunset within that period. (Many of the provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which was passed under reconciliation, included such sunset dates.)

There is one similar proposal on offer that would make the child benefit permanent by including pay-fors—Sen. Mitt Romney’s, which, as we covered at length last month, would satisfy reconciliation’s deficit neutrality requirement by eliminating a thicket of other family welfare programs as well as the state and local tax deduction. It’s unclear whether Biden’s comments were meant to indicate he was open to an arrangement like Romney’s in the current bill or simply that he wants to achieve a permanent child allowance via legislation down the road.

Even if Democrats did warm to the Romney arrangement, it’s still unlikely the final vote would look very bipartisan: On top of the many extraneous critiques of the bill mentioned above, many prominent Republicans have bristled at Romney’s approach to child welfare, objecting to its lack of work requirements for parents to qualify. Sens. Mike Lee and Marco Rubio, who have previously pushed for an expansion of a parallel policy, the child tax credit, accused Romney’s proposal of “undercutting the responsibility of parents to work to provide for their families.” Oren Cass of the pro-family group American Compass—who also happens to be Romney’s former policy director—offered many of the same critiques this week in the New York Times.

“To strengthen a nation’s commitment to shared expectations and obligations,” Cass wrote, “and to sustain broad-based political support, a program should ask recipients to do their part in supporting themselves.”

Ultimately, the intraparty disagreement boils down to this question: What is the primary aim of the social safety net? Proponents of attaching work requirements to all forms of welfare argue that such programs exist to alleviate the worst effects of poverty while also taking pains to ensure that recipients are first supporting themselves to whatever degree they are able. But proponents of plans like Romney’s argue that family policy in particular should take into account that children are a societal good in and of themselves—even when considered from a bloodless economic perspective—since children are necessary to replenish the stock of future taxpayers.

This difference in perspective leads to some interesting downstream wrinkles as well. For instance, American conservatives tend to characterize themselves as proponents of “small government.” But factions within the conservative movement disagree on whether the interest of “small government” is served by a frequently confusing and bloated bureaucratic compliance regime set up to ensure that only people who deserve welfare benefits receive them. This distinction was on full display in an American Enterprise Institute (AEI) debate on the child allowance policy that took place Tuesday: AEI’s Scott Winship, who opposes the Romney plan, lamented that caseworkers tend to get a bad rap, while economist Lyman Stone, arguing in favor, took the opposite view. (Both Winship and Stone have written for The Dispatch.)

“The point is that while child allowances may risk expanding the total size of government, they also dramatically reduce the intensity of the intervention of that government,” Stone said. “I don’t think we should act like the median [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] caseworker is our ally in advancing a conservative social vision. And I think generally the bureaucracy is not an ally to conservatism.”

If Democrats stick with their own child allowance plan and manage to pass their stimulus bill, there will be at least one benefit for Republican lawmakers and wonks: By the time the issue comes around for a vote again, they’ll have had a full year to try to put these differences to rest.

Worth Your Time

-

According to David Shor—head of data science at OpenLabs, a progressive nonprofit—support for the Democratic Party from 2016 to 2020 trended downward by roughly 2 percent among black voters and 8 or 9 percent among Hispanic voters. Eric Levitz of New York magazine spoke with Shor last week to dissect these trends. “Over the last four years, white liberals have become a larger and larger share of the Democratic Party. There’s a narrative on the left that the Democrats’ growing reliance on college-educated whites is pulling the party to the right,” Shor said. “But I think that’s wrong. Highly educated people tend to have more ideologically coherent and extreme views than working-class ones.”

-

How should we define “populism” today? Is it different from nationalism? Will Trumpism be on the ballot in 2022? National Review senior writer Michael Brendan Dougherty joined the New York Times’ Jane Coaston and Ross Douthat on the latest episode of The Argument podcast for a lively discussion about the GOP’s present and future. “[Conservative populism] doesn’t deliver enough things to enough people, and it makes enemies out of too large a share of the American public to govern the country effectively. And therefore it doesn’t govern the country effectively, and it remains a, at most, 46 percent, 47 percent movement,” Douthat argued. “The point is to divide the country and get 60 percent of the vote, and that’s something that nobody in our politics has done for a long time. But we remember our most successful presidents because they were able to do that. That’s the actual goal here, right? It’s to build a populism that doesn’t make people who are not, in fact, elites feel like they’re being scapegoated all the time but that does, in fact, punish the people in charge by removing them from power, at the very least, when they preside over a bunch of disasters.”

Presented Without Comment

Toeing the Company Line

-

Jonah’s Wednesday G-File (🔒) focuses on the avalanche of karma headed toward New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Not only is Cuomo under investigation for alleged sexual impropriety and an alleged cover-up of the number of nursing home deaths in New York, he’s also weathering this storm after years of belittling his political enemies, morally grandstanding about the MeToo movement, and criticizing Trump for his mishandling of the coronavirus pandemic. “The post-MeToo standards are real, and Cuomo and his party have been at the vanguard of the effort to establish them,” Jonah writes. “One of the first rules of politics is that if you’re going to apply strict standards to others, you should adhere to them yourself.”

-

On Wednesday’s episode of the Dispatch Podcast, the gang discusses President Biden’s COVID-19 stimulus package, voting rights in a post-Big Lie world, the ongoing situation in Afghanistan, and how the GOP is hoping to retake the House in 2022.

-

If you liked yesterday’s TMD item on semiconductors and supply chains, you’ll love Scott Lincicome’s latest Capitolism newsletter(🔒). “Federal government attempts to reshore supply chains raise their own risks,” he argues. “Freer markets can bolster U.S. resiliency by increasing economic growth, mitigating the impact of domestic shocks, and maximizing flexibility in times of severe economic uncertainty.”

Let Us Know

Over on the site today, contributor Nicholas Clairmont writes about the decision by Dr. Seuss Enterprises to no longer publish six Seuss books because of depictions that are now considered racist. That has prompted not only debate but also nostalgia for many of Suess’ other titles. Did you grow up reading any of them? Which are your favorite? Feel free to explain in rhyme.

Reporting by Declan Garvey (@declanpgarvey), Andrew Egger (@EggerDC), Haley Byrd Wilt (@byrdinator), Audrey Fahlberg (@FahlOutBerg), Charlotte Lawson (@charlotteUVA), Ryan Brown (@RyanP_Brown), and Steve Hayes (@stephenfhayes).

Correction, March 4, 2021: Joe Biden’s coronavirus stimulus package is nearly $2 trillion, not $2 billion.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.