Pulled Pork Tacos

A year later, the question everyone seems eager to answer is whether the Supreme Court meaningfully changed American politics with its Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision. My best answer is: kind of, not really, depends on who you ask.

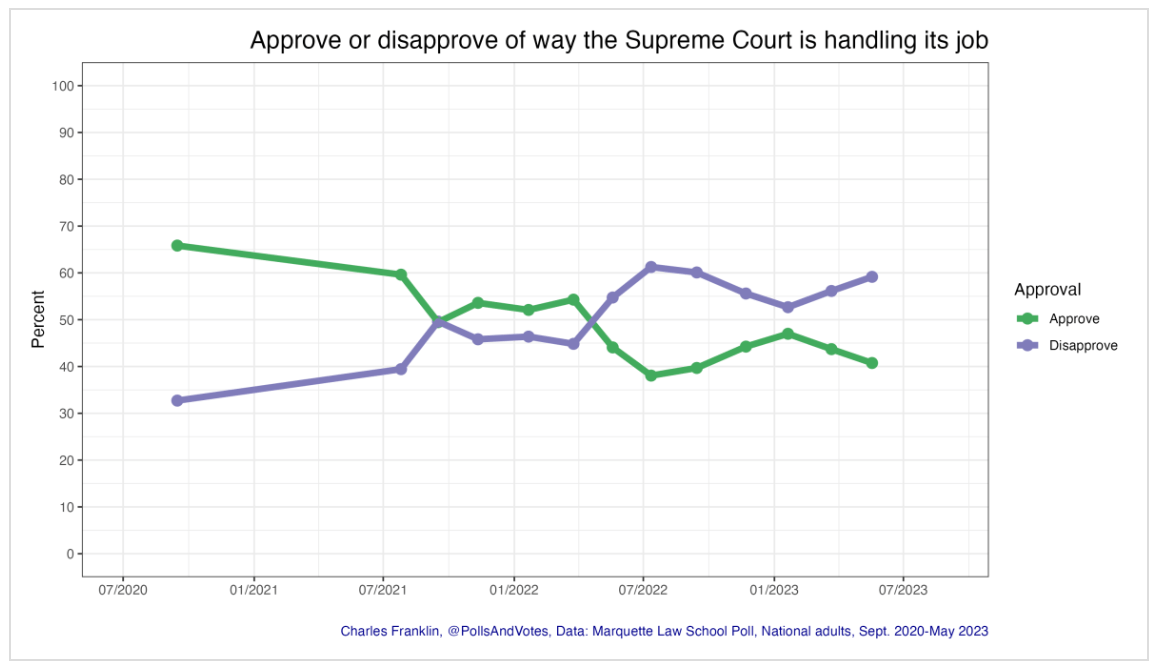

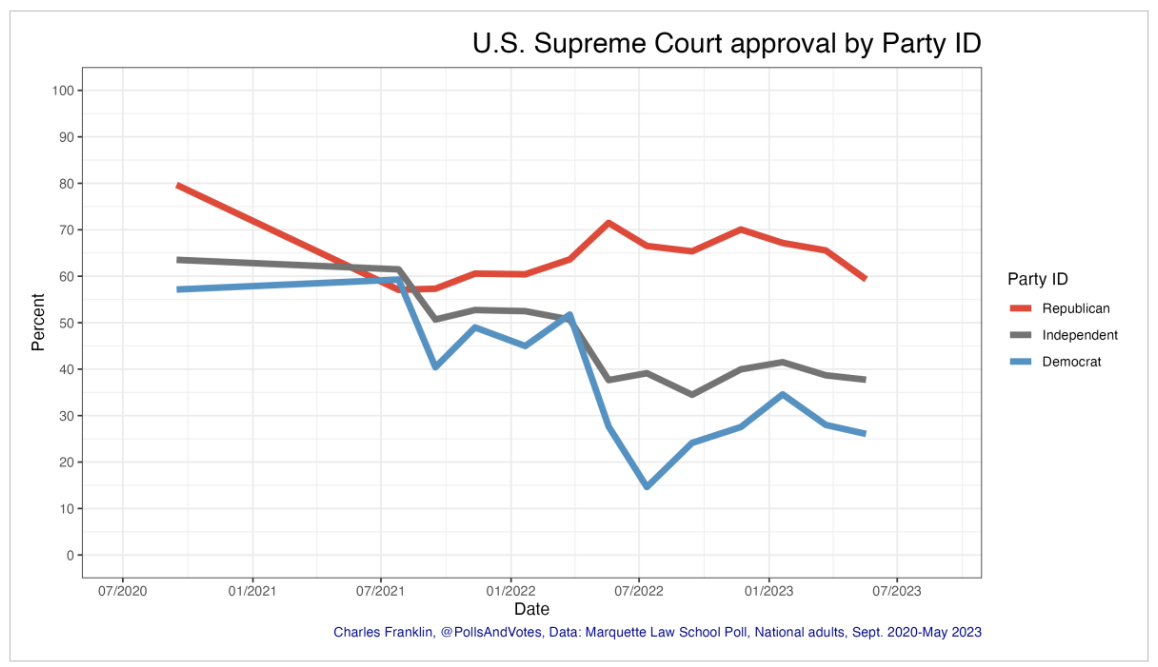

Let’s start with “kind of.” The Supreme Court’s approval rating as an institution has taken a dive in the past year. In the wake of Dobbs, we heard a lot about the perceived illegitimacy of the Court among large numbers of Americans—most dramatically on the left. What’s more interesting is that those numbers started to rebound six months later. But before we could see whether they’d spring all the way back, the court was hit by a series of stories questioning the ethics of several of the justices. The numbers plummeted again.

Which direction does the causal arrow point to? Information about the Supreme Court is very low among the general public. In this same survey, Charles Franklin over at Marquette Law School—who always does fantastic SCOTUS polling—found that “30% of the public believes a majority of the justices were appointed by Democratic presidents.” And this isn’t just that they missed the 6-3 Republican appointed majority. The last time there was a majority of justices appointed by Democratic presidents was 1969. (Remember: Earl Warren and William Brennan were Eisenhower appointees.)

And we could follow up this statistic with all sorts of “oh right, Americans know very little about the Supreme Court unless it’s in the news every day, which is almost always going to be negative coverage” data. Roughly three out of four Americans haven’t heard enough about Justices Alito, Gorsuch, and Kagan to even have an opinion of them. And the most well-known justices—Thomas and Kavanaugh—still have over 40 percent of Americans who don’t know enough about them to have an opinion.

In that sense, Dobbs did kind of matter. Democratic activists want to drive the Supreme Court as a voting issue, which has favored Republicans for a long time. Given how little information most voters have on the Supreme Court, this has allowed the left to drive down approval ratings by snapping their fingers. The fact that we can see a dip after Dobbs and another dip after the transparency and ethics stories tells me that whatever message the left drives about SCOTUS has its intended effect. It’s bad for the court and I’d argue bad for the country, but it’s politically advantageous in the long term to build wedge issues piece by piece.

But in another sense, the answer is “not really.” Recently, Patrick Ruffini over at Echelon Insights was doing a deep dive into some Latino voter polling that “reveal the interesting ways that issue priorities are really a proxy for political knowledge, not a driver of turnout in and of themselves.” That is, it’s easy to look at a poll that says “these voters cared about abortion a lot” and “these voters turned out to vote at high numbers” and say that abortion led to higher turnout. But Patrick’s argument is that, in fact, when you ask high propensity voters what issues they care about, they are more likely to give an answer they heard on MSNBC (democracy, abortion, MAGA extremists) and the less engaged voters are more likely to give one that’s more universal (the economy, inflation, etc.). As he put it:

The people tuned into “threats to democracy” skewed very MSNBC, not only in the sense of being partisan Democrats, but in seeking out more niche, upscale media outlets covering these issues disproportionate to the economy. Abortion did have more resonance with the low-propensity voter, but it wasn’t an issue that universally touched everyone like inflation did. And so the people who said that the economy was their top priority likely skewed low-information and low-turnout in a way that wasn’t captured by other ex-ante variables.

In other words, the issues didn’t drive the turnout; the turnout propensity drove what issues these voters were exposed to in the first place. And that means maybe the Dobbs decision hasn’t really mattered much as a political issue at all.

But then it also “depends who you ask.” Data is great, but something to be said for the experience operatives are having on the ground and what you can see with your own eyes. On the one hand, conventional wisdom tells us that Dobbs has helped Democrats. And there’s plenty of evidence to back that up. Democratic candidates ran on the issue; Republican ones had panic in their eyes when asked to take a position and often said something like “that is an important question that the American people know is …. Squirrel!” Ballot measures in red states like Kentucky and Kansas showed voters in favor of at least a pre-Dobbs status quo and maybe more. And the Wisconsin Supreme Court race is a good example of the pro-choice candidate stomping the pro-life candidate in a swing state. And polling pretty consistently shows people don’t like the Dobbs decision and are leaning more pro-choice than they were pre-Dobbs.

On the other hand, pro-life candidates beat pro-choice candidates and vice versa. Look at Georgia. In the governor’s race, Brian Kemp ran on his very pro-life record and beat Stacey Abrams who ran on her very pro-choice policies. But in the U.S. Senate race, pro-choice Sen. Raphael Warnock beat pro-life candidate Herschel Walker. And if you’re screaming at me that Abrams had a “defund the police” problem or that Warnock was an incumbent or that Walker had an “everything under the sun” problem, I agree. That’s the point. Abortion wasn’t an important enough issue to voters to overcome the underlying dynamics of these races.

And there’s one other data point worth mentioning: The number of abortions hasn’t really changed much in the past year. Which means something we already knew all along—the law rarely drives cultural change. Just check out how school desegregation went in the year after Brown v. Board of Education. (Spoiler alert: It didn’t.) Banning abortions and saving unborn lives was never the same goal. So if the goal of pro-lifers is to reduce the number of abortions, reversing Roe was never going to be the finish line.

Tableside Guacamole

I was reading this piece about South Korea’s catastrophically low birth rate and the rise of “no kid zone” and “no old people zone” restaurants and coffee shops as the “parent class” shrinks and the younger, childless, disposable income cohort find the growing number of old people annoying. That’s a funny-if-weird cultural story, but politically, it’s a catastrophe. The result will be a country with a lot of old people depending on a big social safety net that nobody is interested in paying for. Sound familiar?

Here’s my question: Our birth rate is at about 1.6, definitely below replacement levels and falling. Why isn’t either political party in the U.S. even nominally interested in making a self interested case to voters on this issue?

Much of the right is against immigration and against social safety net reforms. But those two things are mutually incompatible. I get that you “already paid into Social Security.” But that money went to your parents. It’s gone now. Who is going to pay for your Medicare? It’s a pretty simple math problem. If there are more retired people (who are living longer) than workers, the system doesn’t work. And workers come from two places—babies and immigrants. The babies aren’t happening. So if you’re going to have a party centered around a cultural anti-immigration message, then you’ve got to have a different solution for safety net solvency. Like all the ones the old GOP had been talking about for 20 years and not actually doing.

The left isn’t much better. They’re pro-immigration and against any changes to safety net programs, which at least might work from a math standpoint. But at its core, their messaging around immigration is that the other side is xenophobic and that we should all be for immigration because that’s what good people are for. But appealing to “be a good person” voters has limits. At least some voters should be amenable to the idea that we need immigrants because they’re the ones who are going to pay for your Social Security. Hell, if we take enough of them, we can even increase your payments to get that boat you’ve had your eye on!

Instead, we appear to have two parties that think babies are going to start falling from the sky any day now. And a generation of olds who aren’t nearly concerned enough about what happens when millennials and Gen Z decide to stop funding baby boomer retirement so they can buy more avocado toast and $8 ice cream cones as a coping mechanism to paper over their own existential dread.

In the meantime, I’ll just be out here as an elder millennial with my mortgage and my 1.77 kids (one kid plus 7 months pregnant divided by 9 months average gestational time) screaming into the void.

Tres Leches

OK, I have to address this because it’s become a thing: No, I did not get a real tattoo! C’mon, y’all. My mother banned me from riding on motorcycles, smoking cigarettes, and drinking coffee (still a drug, in her view). I’m 40 years old and I’ve never tried marijuana. I’m like a lifetime marshmallow test. And y’all thinking I’m up and getting a sleeve tattoo at 7 months pregnant? That being said, it’s an awesome tattoo and I’m very grateful to Jonah for supplying me with enough temporary ones to last me through the summer SCOTUS opinion drought.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

You are currently using a limited time guest pass and do not have access to commenting. Consider subscribing to join the conversation.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.